Revisiting the Zeitgeist of Kim Beom 1) : The term 'Zeitgeist' refers to the

the 1995 Roundtable Mo Bach and the 1998 exhibition Seoul in Media

권화영 저, 김나라 역

Introduction

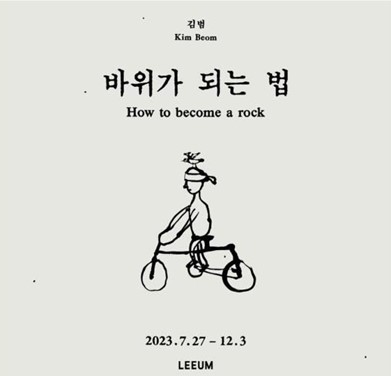

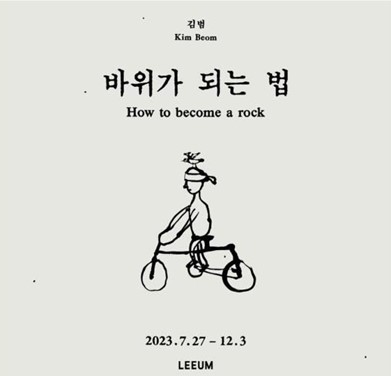

In 2023, the Leeum Museum of Art presented one of the noteworthy exhibitions in the second half of the year, Kim Beom’s How to Become a Rock. Comprising the bodies of works over a span of 30 years, the exhibition was named after the chapter 4 of one of his artist books, The Art of Transforming(1997), which proposes the absurd idea of “how to become a rock” in a serious manner. 2) The exhibition poster is also striking—a childish drawing depicting a boy, awkwardly riding a bicycle with one eye blindfolded.

Figure 1. The exhibition poster of

How to Become a Rock

The exhibition title and poster, both chosen by the artist, succinctly sum up his artistic practice of circumlocution to disclose the absurd of reality in a witty yet incisive way.

After receiving B.F.A.(1986) and M.F.A.(1988) in painting from Seoul National University, Kim moved to New York in 1991 to complete masters’s degree at School of Visual Arts. He has participated in numerous exhibitions and biennales both domestically and abroad, starting to present his works at international stages such as the 2nd Gwangju Biennale: Unmapping the Earth-Speed, Space, Hybrid, Power, Becoming(1997), Seoul in Media-Food, Clothing, Shelter(1998) and the 2nd Taipei Biennial: Site of Desire(1998). Also, Kim was recognized as a major artist in contemporary Korean art, winning the 15th SukNam Art Award(1995) and the 3rd Hermes Korea Art Award(2001). Despite these acknowledgments, most of the previous studies on the artist focused on analyzing specific artworks, leaving room for a broader perspective over the horizon of Korean contemporary art.

To this end, the article begins with comprehensive examination of the domestic and international conditions and the changes in Korean art scene during the 1990s when Kim Beom started his artistic career to contextualize his work. Drawing on diverse factors as analytical agents, it is to demonstrate that the works by Kim Beom reflected a new trend as a zeitgeist that responded to the social and political demands of dynamically changing period. By delving into two particular events—the roundtable, Mo Bach (1995) and the exhibition, Seoul in Media – Food, Clothing, Shelter(1998)—this article, moving beyond an analysis of individual pieces, aims to broaden the significance of Kim Beom's practice towards the expanded field of Korean contemporary art.

Korean Contemporary Art in the 1990s and the Zeitgeist in Kim Beom’s Works

Korean Society and Contemporary Art in the 1990s

“ All artists bear the imprint of their time,

but the great artists are those in whom

this is most profoundly marked.”

- Henri Matisse 3)

As Matisse once said, art and the era to which it belongs are indivisible. Likewise, to fully grasp Kim Beom's works, it's essential to look back the 1990s when he began his active involvement in the domestic art world. This era marked a paradigm shift on a global scale with successive historical events: the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, and ultimately, the end of the Cold War in the post-Soviet aftermath. Witnessing economic globalization unfolding in full measure, South Korea also embarked on its own journey to the “Global Village,” taking the opportunity to host the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul, a crucial point of international connections. Elected as the president in the civilian government upon the democratic transfer of power in 1993 after the despotic governments, Kim Youngsam administration declared internationalization project, or “Segyehwa” (世界化, globalization), as the fundamental direction of its national policy. Especially, following the launch of the World Wide Web (WWW) on August 6 in 1991, the availability of broadband internet in 1999 accelerated the global distribution of information across multiple points through multiple channels and enabled the temporal simultaneity.

At the same time, globalization was a forceful tow toward neoliberal economy. South Korea strategically aligned itself with the reformed global economic order during the post-Cold War era by officially joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) and, the following year, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), positioning itself closely with the United States. Culturally, the society embraced diversity and actively engaged in discussions on the latest Western theories, such as postmodernism and multiculturalism. 4) With per capita income surpassing ten thousand dollars in 1996, the state entered an era of mass consumption witnessing rapid advancements in mass culture. However, amid the ideological shifts of the 1990s when traditional concepts such as 'nation,' 'nationality,' and 'collectivity' began to lose their significance, people increasingly turned their focus towards personal and individual interests rather than broader public concerns.

As the political initiative of Segyehwa unfolded, the Korean art scene entered new phases influenced by international trends. In 1993, the '93 Whitney Biennial in Seoul was hosted by the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), alongside the Daejon Expo '93 at the EXPO Science Park. This period marked a diversification of Korean art, highlighted by the Ministry of Culture and Sports' declaration of 1995 as 'the Year of Art.' The Korean Pavilion made its debut at the Venice Biennale in the same year and the Gwangju Biennale was inaugurated under the title 'Beyond the Borders.' Furthermore, the art infrastructure expanded with the establishment of new museums, alternative spaces, art magazines, and educational institutions. Following the reorganization of the MMCA with a new branch in Gwacheon in 1986, numerous public and private museums were founded from the 1990s to the early 2000s.5) The proliferation of art periodicals facilitated communication and discussions within art criticism circles. 6) Alternative spaces outside conventional institutions offered young artists opportunities for experimental freedom. 7) In line with the liberalization of overseas travel in 1982 and increased possibility of studying abroad the next year, more and more Korean artists gained exposure to the global art scene. In tandem with the liberalization of overseas travel in 1982 and increased opportunities for studying abroad the following year, more artists gained exposure to the global art scene. Domestically, the Korean art world saw a shift away from the dominance of two major academic institutions—Seoul National University and Hongik University, both based in Seoul. This change followed the establishment of new art colleges such as the Korea National University of Arts (KNUA) and the Samsung Art and Design Institute (SADI), along with the rapid growth of smaller ones including Gachon University, Kookmin University, and Hansung University. 8)

New era demanded new sensibility. In a 1993 feature article, “New Sensation and Communication—Public Media Art: Changes in Visual Environment and Search for New Ways of Communication,” the introduction noted, “Since the 90s, a group of artists has been emerging with a new sensibility.” It was evident that a resonance was beginning to take shape between the younger generation and young artists, who radiated a new spirit distinct from the previous generation. Um Hyuk emphasized the importance of a flow of social changes to study the distinctions in art between the 1980s and the 1990s for art is inevitably subject to its political and economic environments.9) Those who grew up during the developmental period of the 1980s belonged to a generation that witnessed the struggle for and achievement of democracy, benefited from the burgeoning middle-class’s newfound wealth, and learned through the evolution of new media.10) This new generation consumed new sensations and cultures, not ideologies.11) These agents of changes with fresh sensibilities brought about a transformation in the art world. When they started their artistic careers, they were relatively free from ideological conflicts or political oppression and more focused on self-awareness and the expression of individuality than on community. It was also the 1990s when Korean art began to break away from the influence of Western Art. Artists in this period less concerned with the external influences; instead, try to construct their inner worlds, seeking new aesthetics that diverged from existing trends. They put into individual practices to answer the fundamental question, “What is art?” 12) Artworks started to reflect the rapidly changing environment—including the rise of mass consumer society, the transition to the digital age, and the emergence of an image-driven culture—with various visual languages. In short, this was an artistic response to social, political, and cultural shifts, an expression of independent zeitgeist in art. Korean art in the 1990s underwent a significant transformation from local to global perspectives, from adherence to rules to self-governance, and from collective identity to individual expression.

Conceptual Work: Mo Bach Roundtable

Kim Beom, referred to as “a leading conceptual artist of our country,” presented conceptual works that were diametrically different from dansaekhwa and minjung art that had long bisected the Korean art during the 1970s and 1980s. The 1990s was a time when the so-called 'first generation of domestic conceptual artists,' including Kim Beom, Bahc Yiso, Ahn Kyuchul, and Chung Seoyoung, made their debut whose works might seem to emphasize content aside from formal aspects. However, Kim Beom has expressed reservations about his work being labeled as 'conceptual art' through interviews. 13) The 'concept' used in the 1990s Korean art was not aligned with the 'form,' 'idea,' and 'content (theme)' sought by previous generations, and Kim Beom's work is not unrelated to this context. To Investigate the essential parts of conceptual work developed at the time, this article pays particular attention to the roundtable related to the 1995 exhibition Mo Bach where the critical discussion on the practice surfaced.

Bahc Yiso, one of the major contemporaries in the 1990s, held his first solo exhibition, Mo Bach, at Kumho Museum of Art after returning from New York. The talks held in conjunction with the exhibition featured Bahc Yiso, artist and critic Park Chankyong, artist Ahn Kyuchul, editor of Hyunsilmunhwa and curator Um Hyuk, and art critic Jung Hunyee; provided a sharp insight on the newly emerging 'conceptual' trend in the country. 14) It is notable that the 'concept' they focused on was contextually different from that of Western conceptual art. Western conceptual art originated from the antithesis of Greenbergian formalism which emphasized the autonomy and visuality of art, as well as the criticism of the art institutions and markets. Simultaneously, it also took its internal methodology from minimalism, the completion and end of modernism. Minimalism, which was almost indistinguishable from objects, radically removed artist's skills and formal aspects in the creation of artworks, eventually evolving into conceptual art that banished authorship and materiality. In Korea, different stories unfolded. As noted by Um Hyuk, who said, “recently, conceptual art has been considered a veiled alternative in 1990s,” the emergence of the term 'conceptual' meshed with the earlier demands for the rethink of the modernism by dansaekhwa and the realism pursued by minjung art, as well as the criticism of the entrenched dichotomy of 'form/content.' 15) Thus, rather than being an artist movement, it was a specific phenomenon caused and observed through a dialectical relationship with previous generations.

Continually, the indiscrimination and misinterpretation of the term was addressed owing to the insufficient consideration of its historical and theoretical contexts. When Western conceptual art is characterized by the intangibility such as 'dematerialization' 16) and the 'use of language,' 17) works by Korean conceptualists like Kim Beom, Bahc Yiso, Ahn Kyuchul show hand-crafted qualities by the artists' meticulous intervention. Ahn Kyuchul pointed out that while Bahc Yiso's work results from a critical stance against the prevalent aestheticism and visual hedonism in Korean art, it is often lumped together as 'conceptual art,' leading to the hasty conclusion that it represents 'art of intellectual taste.' 18) Similarly, Um Hyuk expressed concerns about inclusively categorizing Bahc Yiso's and Ahn Kyuchul's works into conceptual art imported from the West 19) Agreeing on the point of the categorization, Park Chankyong suggested that the term be able to be broadly used to mean 'art that contains thought' or in terms of 'art methodology.' What she meant by art methodology refers to what Ahn Kyuchul described as 'schematic' art, meaning art where the relationship between “thought by language and concept” and “material and form“ together constitutes the working process.“ 20) Admitting that, from aestheticism, his work might be read as 'content-oriented,' he clarified that the relationship between thought/material and concept/form in his works is inseparable and integrated in their structure, thereby being independent from those of Western conceptual art. 21)

Likewise, to fully understand Kim Beom’s work as conceptual art, it must be examined within the specific contexts and various dynamics of Korean art. His abandonment of formal beauty and visual pleasure does not mean his blind pursuit of content and idea. Rather, he defines 'another form' on his own that diverges from the formal aesthetics defined by the established mainstream. In this way, he diverts from the aesthetic meaninglessness of conceptual art—considered as 'the monstrous myth of post-medium condition' by Rosalind Krauss—that negates the importance of the medium. 22) This distinguishes Kim Beom's work from Western counterpart, which overreached itself in the extreme of dematerialization, asserting “the idea becomes a machine that makes the art.” 23)

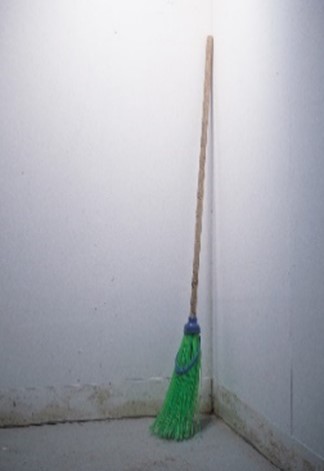

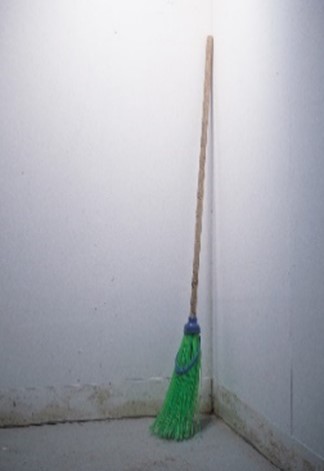

An example of the use of the concept as 'art methodology' is Untitled(A Job on the Horizon)(2005).

Figure 2. Untitled (A Job on the Horizon), 2005, broom, 164 x 21 x 17 cm.

This work, a broom used for cleaning a yard, performs the original task of sweeping away the museum floor throughout the exhibition. In that the subtitle A Job on the Horizon directly represents the broom's function of sweeping up garbage, it shows a self-referential quality. Particularly, the use of the ready-made reaches back to conceptual art. 24) However, while Duchamp's ready-mades were strategies of anti-aesthetic statement, Kim Beom’s ready-mades function as a 'form' of the 'content,' which addresses the theme of “the cycling lives of objects according to the meaning that human beings give them, and mourning for their loss.' 25) In other words, his work is composed of both contents and forms. Further, by carefully carving a detailed relief into the long wooden handle, Kim Beom adds a crafty aesthetic and makes an ordinary object a unique artwork. This approach reminds of a modernist attitude that maintains a faithful commitment to form which is central to the essence of art.

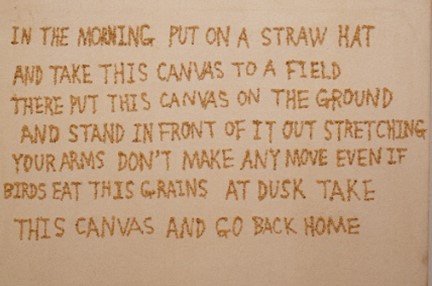

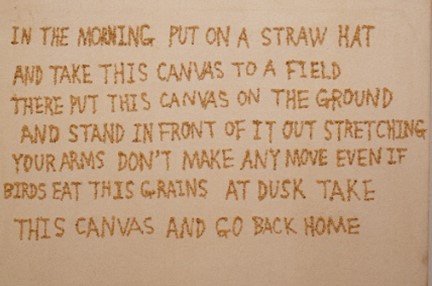

Artist’s text-based works also evoke conceptual art. However, while Western conceptual artists used language as a strategy of negating pure opticality of modernism, Kim Beom employs it as a medium of new painting. In contrast to the traditional approach where an artwork was completed by an artist with brush, in Kim’s works, text mediates the viewers’ imagination effectively turning them into the creators of the works. Particularly, unlike artists like Sol LeWitt or Lawrence Weiner, Kim Beom reveals his own clumsy style of handwriting. For example, in Scarecrow(1995) 26) the instructions written with pieces of grains, as Untitled (A Job on the Horizon) reveals its craftsmanship, lead the viewers to an imagery of scarecrows guarding fields, This approach contrasts with Lawrence Weiner’s claim that if the propositions are conceptually valid, there is no need for a physical work. 27)

Figure 3. Scarecrow, 1995, grain on canvas, 65.5 x 92 cm.

Thus, Mo Bach roundtable, a significant site of intense discussion on conceptual art, not only identified the conceptual work as the emergent practice of art to replace the conflicting establishment—the form-oriented Dansaekhwa and the content-oriented Minjung art—but also shed light on the unique characteristics of conceptual art in the Korean contexts.

Expansion of Medium: Seoul in Media – Food, Clothing, Shelter(1998)

Three years later, an exhibition, held at the temporary commemorative hall for Seoul’s 600th anniversary, marked a significant turning point in contemporary Korean art. The exhibition, titled Seoul in Media – Food, Clothing, Shelter(1998) and curated by the curator and critic Lee Youngchul, visualized the theme of 'individuals,' which had been paving its way crossing away from long-standing nationalistic concerns, through the most everyday subjects of food, clothing, and shelter.

Figure 4. Installation view of the exhibition, Seoul in Media – Food, Clothing, Shelter(1998)

Lee showcased extensive works of contemporary trends that blurred the boundaries between art and everyday life, as well as art and other fields, signaling the internationalization of Korean art. 28) Beyond the artworks themselves, he introduced a new theme and presentation design in a way unexampled in the country.

A news article described the exhibition stating, 'Rather than art pieces, everyday items are brought directly into the exhibition space, and the place, supposed to be solemn, is struck as a construction site. [...] Not only the interior of the museum, but also the entrance and walls of it, bus stops, and street billboards become parts of the artworks.' 29) This indicates that the exhibition boldly experimented in a way that was entirely different from the mainstream art of the time. In other words, the exhibition aimed not to highlight the theme of everyday life but to represent everydayness itself. In the exhibition preface, the curator explained, 'Emphasizing the theme of an exhibition can result in neglecting the externality formed by the relationships, processes, and events related to the works. Thus, in contemporary exhibitions, there is a growing tendency to place less importance on subjects and this exhibition is based on this idea.' 30) The exhibition was an attempt for several reasons: 1) it was the first exhibition curated with full authority by a curator, 2) it presented the discourse of 'everyday life,' 3) it pursued the viewing method of contemporary art, 'open interpretation,' and 4) it introduced a innovative spatial design that differed from previous standardized plan by creating a 'construction site.'

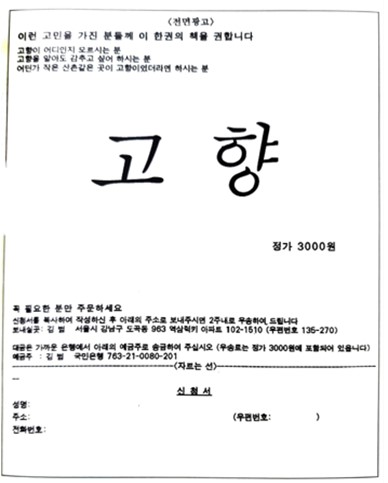

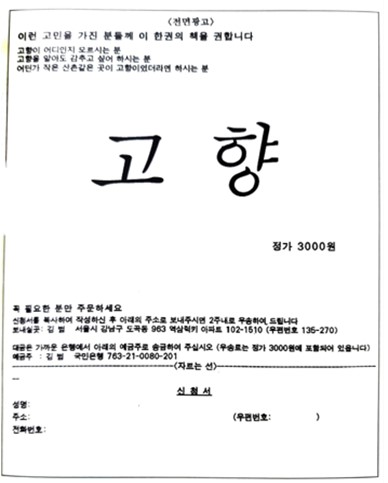

Kim Beom participated in the exhibition with an artist book, Hometown(1998).

Figure 5. Kim Beom, Hometown(1998), leaflet displayed at Seoul in Media

But the visitors were unable to view it in person inside the exhibition hall. To see the work, they had to fill out an application form, transfer 3,000 won to a designated account, and then wait for the ordered book to be delivered by post. 31) The book describes a village, 'Unge-ri' Jinbu-myeon, Pyeongchang-gun, Gangwon-do. This village, however, is a pure imagination—it’s a fictional place in real town, Jinbu-myeon. Though, Hometown has a clear purpose: it was intended 'for those who may not know where they come from, or for those who, even if they know, want to hide it.' 32) In short, the work was created to provide individuals with a fabricated hometown they could rely on. So, it offers made-up but very convincing information in detail, nonchalantly covering every aspect of this non-existent village: from its location and the surrounding environment to the geographical layout, the lifestyle of its residents, and the population distribution, as well as the specific figures living in the village and legends passed down through generations. 33) The artist also elicits a laugh with a whimsical yet meticulous request that after 10 years, when the information about this hometown is assumed to remain undisturbed by the world’s changes, readers agree that 'when telling stories about hometowns, let's say you haven't visited Unge-ri recently.' Through this, the artist creates a secret between himself and readers; this approach indicates what a new generation has valued, not through the serious ideologies pursued by previous generations, but through the idea of 'serious lightness,' much like in his fist artist book, The Art of Transforming(1996).

An important aspect of the artwork is that the hometown usage guide was not effective to those who didn’t order the book. This process encouraged a new way of appreciating art and offered a novel form of participant performativity, allowing each viewer to complete the work in their own place. Notably, Hometown aligns with the concept of imagery in painting, imbuing an invented narrative with a sense of actuality. This positions the work as a kind of meta-painting, or a 'painting about painting,' which questions the history of image creation in the medium of painting. It also exemplifies 'expanded painting,' demonstrating how the medium can transcend traditional boundaries and extend into other forms. At the same time, it represents 'another painting' that diverges from the values pursued by dansaekhwa and minjung Art.

In the 1990s, Korean art faced criticism for its failure to capture the signs of changing times and a growing necessity for the active use of new mediums, leading small groups of artists to spearhead a shift. 34) At this juncture, contrasting with the trend of small groups’ exhibition held in project-based temporary spaces, the exhibition Seoul in Media provided a comprehensive showcase of the new generation's works within a institutional stage, clearly demonstrating the shifting cultural landscape. 35)

The period marked the rush of students returning from abroad, especially after the IMF crisis in December 1997. Most of the featured artists—Kim Beom, Yang Haegue, Ahn Kyuchul, Yee Sookyung, Hong Seunghye, Ham Yangah, Ham Kyungah, and Lim Minouk—were relatively unknown, young, and recent returnees. 36) These artists moved beyond traditional fine art, reflecting the new currents of Western contemporary art by embracing various mediums such as video, installation, design, photography, animation, typography, architecture, computer, and sound. Their unconventional approaches expanded the scope of mediums and broke down the conventional boundaries between techniques, genres, and styles as previously defined. This new spirit was vividly visualized throughout the exhibition, signaling its imminent penetration into the Korean art world.

After 1990, when formalist mannerism—characterized by a habitual and distinctive style—had lost its place, Korean art entered an era of pluralism opening its door to diverse and hybrid styles and mediums as defined by art historian Yun Nanji. 37) The exhibition Seoul in Media was a milestone, or a turn of generations in the Korean art which rejected a single line of its cultural axis. The works of fledgling artists in the country like Kim Beom became recognized as new art to substitute for those of full-fledged generation, nesting on Korean art as the zeitgeist of the contemporary. Moreover, starting to establish themselves as artists, most of the participating artists influenced the development of alternative art spaces, which began to flourish domestically from 1999, and now have been regarded as the major artists. Kim Beom's work is a product of the complex relationship between the rapidly changing Korean society of the 1990s and the Korean art world. His work has thus located itself as a visual viewpoint of the cultural and geopolitical landscape of contemporary Korea.

Conclusion

Each era has resonating art with the sensibilities of its aesthetics. No exception was the 1990s' Korean art. The practice of the emerging artists during the decade reflected the evolving social consciousness, both domestically and internationally, transforming the internal context of art. This movement was engaged with the surfacing demands diverging from the past—specifically, the demands of hybrid, heterogeneous, and multifaceted aspects of the 'here and now' 38) Art historian Shin Chunghoon observed that by the 1990s, there was an inevitable connection between Korea's socioeconomic conditions and a younger generation of artists with new sensibilities and suggested that this connection be discussed as another essential part of the contemporaneity of Korean art. 39) In this context, this essay posited Kim Beom's work as the embodiment of the 'zeitgeist' that departed from established culture and embraced the new spirit of the time. His work was as a reflection of the new sense of temporality brought about by the shifts in social, political, and cultural perceptions in 1990s' Korea. To support this claim, the essay examined two significant events aiming to situate Kim Beom's work within the varied topographies of contemporary Korean art. This approach came from the belief that ‘Historic narrative of the practice of an artist must be preceded by the contextualization within its time.’

Kim Beom's work holds significance today as before in understanding art. The pluralistic trends at present—characterized by the dissolution of boundaries between genres, the expansion of mediums and subjects, and the pluralized identity of artists who actively engage in creation, curation, critique, and administration— started off during the last decade before the 21st century. Subsequently, Korean art changed its focal point from defining Korean identities or ideologies, and comparing with Western art to opening up new horizons for Korean contemporary art, leading to the vibrant today. Kim Beom's comprehensive and all-encompassing approach, through which the artist utilized different mediums such as painting, drawing, sculpture, installation, video, and artist book, had a profound influence on art onwards. Passing through transitions from the digital era to the post-digital and post-internet era, now we are in an age of artificial intelligence and art medium is, once again, going through the expansion. 40) Traversing both online and offline spaces, artistic experimentations are traveling in new concepts and aesthetic experiences. Kim Beom’s 'new art' by 'new media' in a 'new era' has been ongoing within different contexts. Tracing the formative points of the narratives is crucial to understand the contemporaneity of 'now.' 41) This is why we should revisit Kim Beom's practice at the moment.

- Nara Kim 김나라 (1993- ) rlaskfk0419@gmail.com

Studied Art History at Ewha Womans University, Seoul, South Korea and currently works at Lehmann Maupin, Seoul, South Korea

이화여자대학교 미술사학과 석사수료 후 현재 리만머핀 서울에서 근무하고 있다.

- Kwon Hwayoung 권화영 (1971- ) rebonhime@naver.com

Studying Art History for doctorate at Ewha Womans University, Seoul, South Korea. Researching 1990s’ Korean contemporary art and lecturing Korean art. Recent writings includes “A Study on Installation Drawings by Yiso Bahc: ‘Informality’ as a ‘Form’ of Postcolonialism”(2023); “A Study on Korean Conceptual Work in the 1990s: Works by Bahc Yiso, Ahn Kyuchul, and Kim Beom”(2024) and They were there. Women who constructed Korean Modern and Contemporary Art(2024).

이화여자대학교 미술사학과 박사과정. 1990년대 한국 동시대미술 연구와 한국미술 강의를 이어오고 있다. 학술논문으로 「박이소의 설치드로잉 연구: 포스트식민주의 ‘형식’으로서 ‘비형식’」(2023), 「1990년대 한국의 개념적 작업 연구: 박이소, 안규철, 김범 작업을 중심으로」(2024)가 있고, 저서로는 필진으로 참여한 『그들도 있었다: 한국 근현대미술을 만든 여성들』(2024)이 있다.

문화체육관광부와 (재)예술경영지원센터의 지원을 받아 번역되었습니다.

Korean-English Translation of this text is supported

by Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism and Korea Arts Management Service

0

0

0

0