정준모

How Artists Are Bypassing Their Dealers and Selling Directly to Collectors

Artsy EditorialBy Margaret CarriganAug 23rd, 2017 5:56 pm

In 2008, Damien Hirst dodged his longtime dealers and took a complete exhibition of his work straight to Sotheby’s. The unprecedented sale surpassed all estimates, bringing in roughly $200 million (of which his galleries at the time, Gagosian and White Cube, did not partake), and raising a major question: Do artists need galleries to sell their work?Hirst’s auction house stunt was made possible by his significant history of commercial success. But a number of emerging artists are toying with the same express route to market, bypassing their dealers in a quest for a greater share of the earnings, a need for quick pocket-change, or the desire to test their e-commerce earning potential. These artists often position their sales as a critique of how the art market functions; taken together, they suggest a growing dissatisfaction with the traditional gallery sales model.Snagging a gallery was once a watershed moment in an artist’s career. Galleries cultivate a collector base, host public exhibitions, take work to art fairs, supplement or advance fabrication costs, and produce publications about the artist, with the goal of ensuring them a place in art history and selling their work. For their efforts, the dealers typically keep 50 percent of the proceeds from a work’s sale.

But for some artists, the lure of 100 percent is too good to resist. Australian-born, New York based artist CJ Hendry spent a year selling her hyperrealist pen-and ink drawings of commercial consumer goods through Instagram, before finding representation with a dealer in Australia in 2014. While she credits him with being instrumental in her career development, she didn’t renew her contract with him when it expired earlier this year, thinking she might try striking out on her own.“I felt like I had outgrown what that relationship could offer me in terms of advancement,” she said.

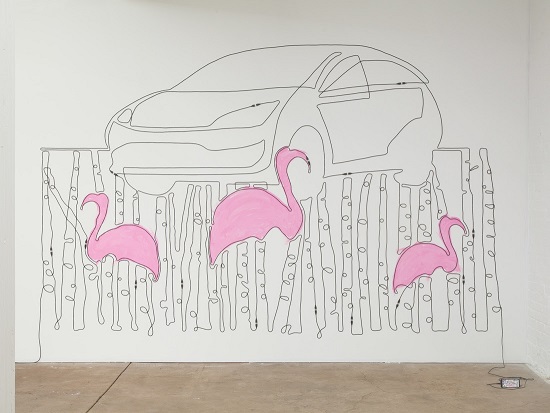

Installation view of CJ Hendry’s collaboration with Louboutin at Art Basel Hong Kong. Photo by @cj_hendry, via Instagram.

She has found brand collaborations to be a viable alternative, noting that the right brand will support her vision and ability to make art, just as her gallery once had. For her first one, with shoe designer Christian Louboutin at Anita Chan Lai-ling Gallery during March’s Art Basel Hong Kong, Hendry presented “Complimentary Colours,” an exhibition of drawings inspired by the shoe brand’s color palette. She negotiated the terms herself, noting that she had turned down many previous offers for brand collaborations until Louboutin, because the company offered her “a lot of autonomy.” For British artist Andy Holden, selling direct-to-consumer wasn’t as much an alternative as a way to rustle up some cash while he was just starting out, living with his parents and “quite cash poor.” He staged his first direct-to-consumer sidewalk sale of his work outside of a three-person show he was included in at London’s Peles Empire in 2006, where he shilled “Beerbottle Stalagmites” just outside the gallery. These were miniature versions of the four-foot plaster and paint sculptural works resembling melting mountains on view in the exhibition, made from leftover materials in his studio, including the empty bottles of beverages he consumed while working. The “original multiples,” as he called them, went for about £30 outside. He has sold an estimated 2,000 of them since then, hawking them outside of different shows, as well as online, keeping 100 percent of the profits, even after he signed with WorksProjects in 2010 (although he parted ways with the gallery in 2014). His brother would often stand by their curbside-parked van, enticing gallery-goers to buy a “souvenir” of Holden’s work from a selection laid out on a blanket at his feet. The sales eventually became a type of self-referential performance art, as when Siobhan Carroll, head of programming at the non-profit Collective Gallery in Edinburgh, asked him to stage one in front of his 2013 solo show at the gallery, “Folly and Landscape.” She said the sale was in keeping with Collective’s interest in “working with artists to consider the politics behind a commercial art space,” and noted she still keeps her own souvenir stalagmite on her windowsill. Holden ceased the sidewalk sale performance after this iteration, but continued selling the beer bottles online until they sold out recently.

Andy Holden, Beer-bottle Stalagmite Sale, 2013. Photo courtesy of Andy Holden.

Brad Troemel and Joshua Citarella, two artists who are currently represented by Marinaro and Carroll / Fletcher galleries, respectively, also started selling work online after a particularly grueling slog through Art Basel Miami Beach in 2015. Each had sold work through their then-respective galleries, but returned home to New York exhausted and somehow still unable make their student loan payments. Their experience is shared by artists, most of whom are notoriously low earners, at all stages of their careers, but younger ones in particular are increasingly likely to have the additional burden of student debt. A 2013 Wall Street Journal analysis found that recent art school graduates in the U.S. have, on average, higher debt and lower salaries compared with peers who went to liberal arts or research colleges.

The duo said they wanted to avoid incurring the additional debt that comes with investing in making work before it’s found a buyer. When artists are tasked with producing a lot of work upfront for shows and fairs, even if dealers provide funds for the materials and shipping, the sale totals don’t always yield enough to compensate them for their labor and time, Troemel and Citarella said.

They decided to launch a new model, an online Etsy store called Ultraviolet Production House, where they sell their collaborative photo-conceptualist works to buyers only after they’ve been paid. The artists prototype an art object by Photoshopping together free stock images they find on the web, list it for sale on Etsy, and promote it on Instagram. Once a work is purchased, they send the materials for its fabrication, but leave assembly to the buyer, like an IKEA for art.

Their “products” are coyly pointless despite sounding utilitarian, intended to critique today’s mindless consumer culture. For instance, one of the items currently for sale on the site, Sage PowerCleanser for Men, is represented by an image of an image of a couple cleaning an apartment, the man holding a Dirt Devil that the artists have Photoshopped sage smudge sticks onto. If purchased for the listed price—$500—the artists would send a hand-held vacuum and some sage.

In May, the duo reintroduced their work into the gallery space at Detroit’s Bahamas Biennale. The exhibition, called “Ultraviolet Production House: Showroom,” was exactly that: a showroom for 20 of their works (all purchased beforehand through a direct deal with a single collector) available through their Etsy store and fabricated for the first time, on site, by the artists. The prices were higher than if they were purchased off the website to reflect what the artists had established as their hourly rate for labor, which varied by piece.

UV Production House, Have A Cord Problem And a Spare Half Hour? Try Using Some of That Excess Length To Liven The Room With a Scene From Your Favorite Planet Earth Episode Including The Commercials That Aired During It. Courtesy of UV Production House.

“If you can buy it off of our website for cheaper, then why would you buy it from a gallery?” said Citarella. “We wanted to open up the question of price-shopping for an artwork like you would any other good.”

It’s worth noting that Holden, Hendry, Citarella, and Troemel have all worked with dealers, and two out of the four still have gallery representation, a fact that reflects dealers’ continued importance in the art ecosystem. But even dealers have been questioning their own relevance in an age when smaller galleries struggle to survive.

London-based art dealer Marine Tanguy broke from the gallery model in 2015, when she started an eponymous agency to support artists and their projects outside of brick-and-mortar gallery spaces; she takes a 30 percent cut, less than the typical dealer’s 50 percent. After managing London’s Outsiders Gallery for over a year and then helping to open Los Angeles’s De Re Gallery, Tanguy decided escalating rents and the merry-go-round of art fairs were making the contemporary gallery business model unsustainable, especially for those working with new artists.

“Growing talent takes time and doesn’t generate a lot of revenue in the beginning,” she said, noting that when an artist does finally achieve recognition, she or he is often scooped up by a bigger gallery. That led her to start looking at art like a used-car salesman, a sure sign she needed to try a new approach.

“While I was working in galleries, I was looking at works of art like retail products that I needed to get off the shelves to make way for new inventory,” Tanguy said.

She said that many of the artists she works with nonetheless go on to sign with a gallery, despite the fact that her agency finds alternative public funding and commissioned projects for them while offsetting their studio costs, much like a dealer would, while still allowing them to show with other galleries.

“I think a lot of artists want to tick that box of having gallery representation,” she said, adding that it offers a certain amount of intangible professional and social validation. “But I think more artists need to diversify their revenue stream nowadays if we want a more responsive model that reflects market realities.”

FAMILY SITE

copyright © 2012 KIM DALJIN ART RESEARCH AND CONSULTING. All Rights reserved

이 페이지는 서울아트가이드에서 제공됩니다. This page provided by Seoul Art Guide.

다음 브라우져 에서 최적화 되어있습니다. This page optimized for these browsers. over IE 8, Chrome, FireFox, Safari