When Picasso Went on Trial for Stealing the Mona Lisa

ARTSY EDITORIAL

BY IAN SHANK

AUG 1ST, 2017 1:14 PM

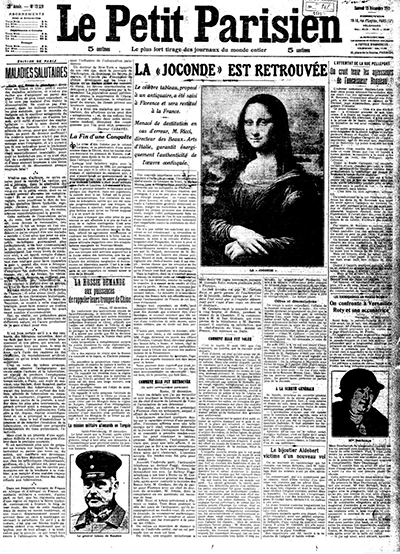

The Mona Lisa on display in the Uffizi Gallery, in Florence (Italy). Museum director Giovanni Poggi (right) inspects the painting. December 1913. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

“La Joconde est Retrouvée” (Mona Lisa Found), Le Petit Parisien, Numéro 13559, 13 December 1913. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

The clock struck midnight. It was time to dispose of the evidence. Stuffing the stolen art into a single oversized suitcase, Pablo Picasso and Guillaume Apollinaire darted from the door of their studio and into the thick summer air. A carriage would be too risky. They would have to proceed on foot.

The pair lugged the valise down the steep, cobblestone slopes of Paris’s Montmartre neighborhood. In the distance the Seine gleamed under the gas lights that still dotted its banks. Had the art been stolen from anywhere but the Louvre itself, perhaps the duo would have been able to temper their panic. For now, the river seemed their only hope.

On August 22nd, 1911—some two weeks prior—the world had been jolted to attention by the breathless declaration of a museum guard as he careened into the office of the Louvre’s director general. The Mona Lisa, the very face of high art, had been stolen.

As news of the theft broke, an international dragnet quickly stretched from Europe across the Atlantic. The borders of France were sealed, and onlookers the world over were rapt and aghast. Yet in many ways, the theft of the Mona Lisa was simply the most explosive in a long litany of embarrassments to the Louvre.

Months before the heist, one French reporter had spent the night in a Louvre sarcophagus to expose the museum’s paltry surveillance. And had he tried, the canvases themselves would have been easy enough to pluck from the galleries. Whereas other prominent national museums, like the Italian Uffizi, had long mandated that its paintings be bolted to the wall, the bulk of the Louvre’s pieces—including the Mona Lisa—continued to hang unprotected. Museum personnel, moreover, were allowed to remove artwork with such unchecked impunity that guards would only report the absence of the Mona Lisa a full 24 hours after its theft, having previously assumed the painting was simply out for maintenance.

Even after the discovery, however, clues were scarce. Days passed. Then a week. Starved for leads, investigators were growing desperate. They needed a break—something, anything, to appease the hundreds of distraught patrons that now marched daily through the Louvre to behold the blank space where the Mona Lisa once hung.

And then, as if on cue, the clouds seemed to part.

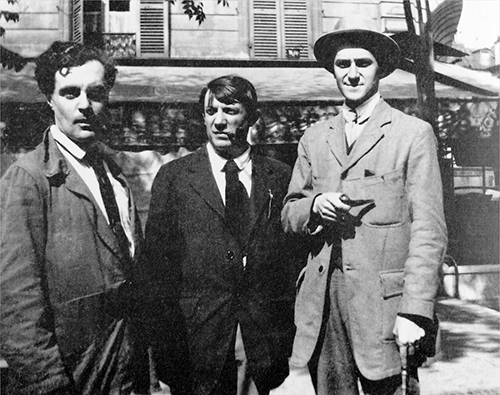

Modigliani, Picasso and André Salmon in front the Café de la Rotonde, Paris. Image taken by Jean Cocteau in Montparnasse, Paris in 1916, via Wikimedia Commons.

On August 29th, eight days after the disappearance of the painting, a young man strode into the offices of the Paris-Journal and began to talk. His name was Joseph Géry Pieret. The paper identified him simply as “the Thief.”

Over several rambling and compensated tell-alls, Pieret recounted that for the past several years he had developed an almost compulsive hobby of lifting and hawking minor artwork from the Louvre. To substantiate his claim, Pieret produced a small statue that was soon confirmed by Louvre curators as an Iberian piece from the museum’s exhibit of pre-Christian artifacts.

The questions came swiftly and hungrily: Was Pieret responsible for the Mona Lisa heist? Did he know who was? On these counts the Thief demurred, sharing only that he had previously sold two other statues to a “painter-friend” in Paris who held a personal fascination with Iberian art.

Suddenly the case had momentum. Although the editors of the Paris-Journal refused to give up the name of their anonymous source to police, the Thief had left a clue—a nom de plume in one of his published confessions, pulled straight from the writings of avant-garde poet Apollinaire. (As police would later discover, Pieret was in fact the writer’s former secretary.) Soon, French investigators were knocking at Apollinaire’s door.

But police didn’t think he had acted on his own. Apollinaire was a devout member of Picasso’s modernist entourage la bande de Picasso—a group of artistic firebrands also known around town as the “Wild Men of Paris.” Here, police believed, was a ring of art thieves sophisticated enough to swipe the Mona Lisa.

There was only one problem: neither Apollinaire nor Picasso had played any part in the painting’s disappearance. Accordingly, the police search of the poet’s apartment failed to turn up any new evidence.

But the two artists were hardly innocent. True to Pieret’s testimony, Picasso kept two stolen Iberian statues buried in a cupboard in his Paris apartment. Despite the artist’s later protestations of ignorance there could be no mistaking their origins. The bottom of each was stamped in bold: PROPERTY OF THE MUSÉE DU LOUVRE.

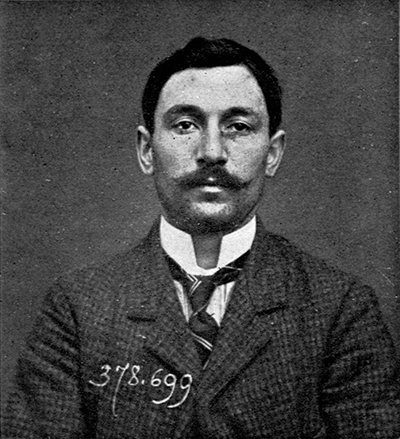

Mug shot of Vincenzo Peruggia, who was believed to have stolen the Mona Lisa in 1911. ca. 1909.

Image via Wikimedia Commons.

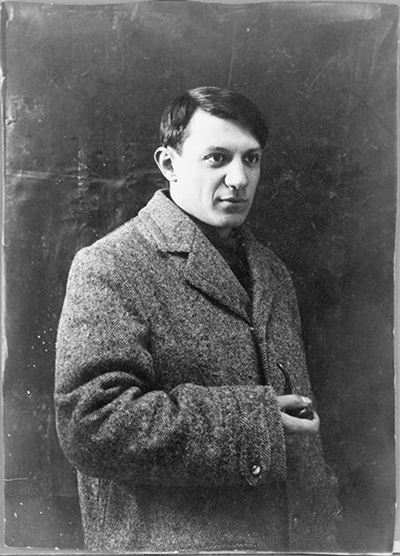

Portrait of Pablo Picasso, 1908. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Stricken with the prospect of deportation back to their native countries, Picasso and Apollinaire had resolved to take radical action, stuffing the two stolen Iberian statues into an old suitcase which they lugged to the banks of the Seine. Yet as the duo stared into the river’s murky waters in the early hours of September 5, 1911, neither could bring themselves to let go.

Somberly, they trudged the three miles back to their studio. Later that morning, Picasso returned the statues to the journal that had first published Pieret’s testimony. Two days later, Apollinaire was behind bars, where he eventually gave up both Picasso and Pieret to police. The writer would spend several days in prison before seeing Picasso again, this time in court as they faced charges for dealing in art stolen from the Louvre.

In the end, the trial played out more as farce than finale. Apollinaire confessed to everything: harboring Pieret, possessing stolen art, conspiring to conceal evidence. Picasso—ordinarily at pains to project male bravado—wept openly in court, hysterically alleging at one point that he had never even met Apollinaire. Deluged with contradictory and nonsensical testimony the presiding Judge Henri Drioux threw out the case, ultimately dismissing both men with little more than a stern admonition. As suddenly as the pair had come under suspicion, they were free.

Two years later, in December 1913, the Mona Lisa would resurface in Florence, its winsome smile as alluring as ever. According to the man who had actually lifted the piece—one Vincenzo Peruggia—his only ambition was to see the painting returned to its native homeland. Today, historians continue to debate the legitimacy of Peruggia’s supposed patriotism. Yet back in Paris, one can only imagine Picasso breathing a long sigh of relief at the news, grateful in the knowledge that his early incrimination had not exiled him back to his own Spanish homeland.

https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-picasso-trial-stealing-mona-lisa