What Makes “Bad” Art Good?

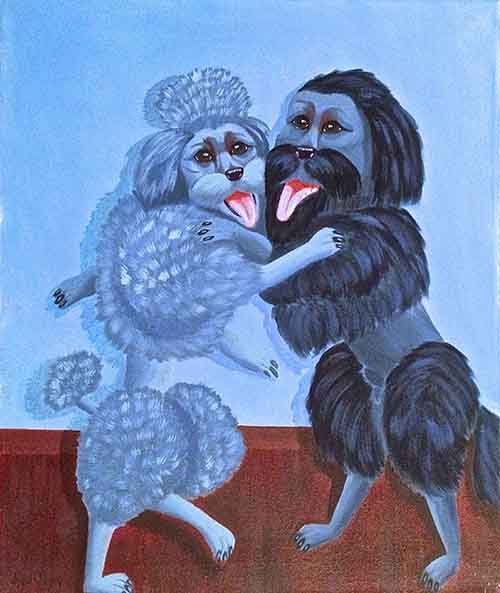

Anonymous, Charlie and Sheba. Courtesy of the Museum Of Bad Art.

Anonymous, Charlie and Sheba. Courtesy of the Museum Of Bad Art.

Occasionally, bad art is easy to spot. Take the famously botched restoration of Elías García Martínez’s Ecco Homo, which transformed the work into the “Beast Jesus,” or the Ronaldo bust that is decidedly less handsome than its source material. Oftentimes, however, the designation is not so obvious.

Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon and Manet’s Olympia were both reviled upon first viewing. (One contemporary critic wrote that the latter resembled nothing so much as “a skeleton dressed in a tight-fitting tunic of plaster.”) These opinions have since been heavily revised, and today both works are considered modern masterpieces—as “good” as art can get.

Understandably, then, the genre of “bad painting” is a slippery one. Rather than a cohesive movement, the label has been applied to a wide-ranging group of artists throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. What they share, wrote curator Eva Badura-Triska in an essay for the 2008 show “Bad Painting: Good Art” at the Museum of Modern Art in Vienna, is a refusal “to submit to artistic canons.”

She goes on to qualify this as a willingness to “oppose not only traditional academic concepts and rules, but also—and this is crucial here—the concepts and rules established by the avant-gardes and isms of the twentieth century, which ultimately threw old dogmas overboard only to replace them with new ones.”

Francis Picabia

Première recontre [First Meeting], 1925

Moderna Musee, Stockholm

René Magritte

Le Stropiat, 1948

"René Magritte: La trahison des images" at Centre Pompidou, 2016

French artist Francis Picabia, for example, could never adhere to one art movement for long. He ping-ponged between Impressionism, Surrealism, and Dadaism, before finally eschewing the art world establishment altogether in the 1920s. It was then, beginning with his “Monster” series, that his painting veered into the realm of the intentionally “bad.”

These bizarre, hallucinogenic works are painted with clumsy brushstrokes and garish colors that belie the artist’s true skill. Decades later, during the start of World War II, Picabia turned to female nudes, sourcing material from movie posters and soft-core porn. Gauche and distasteful, several of these paintings actually ended up in North African brothels serving Nazis and Italian Fascists during the occupation.

These phases of Picabia’s work can be seen as a precursor to later artists who dabbled in bad painting, including René Magritte and his 1948 période vache. Although the Belgian painter’s best-known works were always unbelievable—men in bowler hats hovering in the air, a daytime sky paired with a street at dusk—they were also crisp and illustrative. His roughly 37 période vache works, on the other hand, were looser and more spontaneous, in the manner of comics or caricature.

As the focus of Magritte’s first Paris solo show, the paintings were meant to offend the Surrealist establishment. (They had the secondary effect of offending buyers; the exhibition was a commercial flop.)

Philip Guston, City Limits, 1969. © Estate of Philip Guston. Courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum.

Decades later, Philip Guston began making work as a reaction against another dominant art movement—Abstract Expressionism. He himself had been a first-generation AbEx painter until the late 1960s, when abstraction began to seem too removed from the tumultuous global political climate. So Guston returned to figuration, populating his paintings with cartoonish hoods reminiscent of the Ku Klux Klan, as well as bulbous, disembodied heads and tangled clumps of legs.

He first exhibited these works in 1970 at Marlborough Gallery, to the shock and dismay of the art world. Hilton Kramer of the New York Times called him “a mandarin pretending to be a stumblebum.”

As Guston began work on these new paintings, across the Atlantic, American artist Neil Jenney was beginning to feel similarly disillusioned with the Photorealist movement. Speaking over the phone, Jenney said that during a 1968 trip to Germany, “the whole scene was suddenly infected by it. And Photorealism was basically second generation pop. Pick an image of America, like a storefront or a pickup truck, and do it over and over again. It was a stale idea done pretty.”

Instead, Jenney thought, “you’d be better if you had a good idea and did it terrible.” So that’s what he did, beginning a series that would later become known as his “bad paintings.”

Neil Jenney

Dog and Boy

Tobias Mueller Modern Art

These works were quite literal, exploring what Jenney called the “narrative potential of imagery” with cause-and-effect titles like Sawn and Saw (1969) or Fisher and Fished (1969). Accident and Argument (1969) depicted the aftermath of a car crash in Jenney’s faux-naive style, the grass a sloppy series of green brushstrokes and the black paint for the asphalt dripping down the canvas.

Whitney curator Marcia Tucker “was the first one to really get it,” Jenney said, and she included one of these works in the 1969 Whitney Annual. A decade later, Tucker featured Jenney’s paintings in a New Museum group show provocatively titled “‘Bad’ Painting.” (It also featured artists such as William Wegman, Joan Brown, and William N. Copley.)

Although Tucker emphasized that “in no way can this work be said to constitute a school or movement,” in her catalogue essay she notes that it is linked “by its iconoclasm, its refusal to adhere to anyone else’s standards of taste or fashion, and its romantic and expressionistic flavor.”

These figurative works were a reaction against both Minimalism and Photorealism, but not in the way that Pop art was a reaction against Abstract Expressionism. Bad painting, according to Tucker, sidesteps artistic “development” in the traditional sense by using unfashionable mediums or styles. “The freedom with which these artists mix classical and popular art-historical sources, kitsch and traditional images, archetypal and personal fantasies, constitutes a rejection of the concept of progress per se,” she explained.

Installation view of Jim Shaw’s “Thrift Store Paintings” at the New Museum, 2016. Photo via

@jenna.kowalke on Instagram.

Eventually, Jenney left bad drawing and painting behind. But the term, coined by Tucker, continued to circulate. German artist Albert Oehlen first heard about the New Museum show when he was a student in the 1980s. “I liked the name, and then, after years, I realized that no one was using that anymore, but it had a big impression on me,” he recalled in a 2009 interview.

Oehlen—and his artistic accomplice at the time, Martin Kippenberger—was out to shock and appall the art world with works like Morning Light Falls onto the Führer’s Headquarters (1983) or Self-Portrait with Shitty Underpants and Blue Mauritius (1984). These vulgar, provocative subjects were shoddily rendered, and Oehlen’s 1983 Self-Portrait as a Dutch Woman earned Kippenberger’s highest praise: “It is not possible to paint worse than that!”

Bad painting collided with outsider art in 1991 at Metro Pictures. California artist Jim Shaw had spent decades collecting paintings from secondhand stores and flea markets, finally exhibiting them in a show called “Thrift Store Paintings.” From Man With No Crotch Sits Down With Girl to Psycho Lady (Shaw titles the works himself), these paintings are delightfully bungled in their execution.

Anonymous, Blue Tango, 2014. Courtesy of the Museum Of Bad Art.

Anonymous, Eyes on the Fly. Courtesy of the Museum Of Bad Art.

Shaw has called them “unquantifiable,” a term that might resonate with the staff of Boston’s Museum of Bad Art. Founded in 1993, the institution avoids collecting the merely incompetent. Instead, said curator Michael Frank, they seek out “pieces that exhibit good technique used to create images of questionable taste.”

Unlike the artists behind many of Shaw’s thrift-store paintings, the “bad painters” of art history were often technically skilled. They made a conscious decision to ignore the standards of good taste and good style, which wasn’t always intuitive. Jenney, for example, said he used to get the itch to fix his bad paintings.

“In the beginning, I said, ‘Whatever happens, I accept it.’ But I did one that had a little boy, and a big glob of green grass landed right on his face.” The rules, he knew, dictated that it had to stay. But “the more I looked, I realized, ‘Wait a minute, that is out of line. That is too distracting, it’s like losing the mood here.’ And I went over and wiped it off while it was still wet.”

There is such a thing as too bad, after all.

—Abigail Cain