Franz Hals, Portrait of a Man, one of a series of Old Master works sold by a French dealer that authorities now believe may be forgeries.

Other paintings are now also implicated, including a Lucas Cranach the Elder, from the collection of the Prince of Liechtenstein, that was seized by French authorities from the Caumont Centre d’Art in Aix in March. An Orazio Gentileschi painting on lapis lazuli, also sold by Weiss, and a purported Parmigianino have been identified as suspect as well. Rumor has it that works by up to 25 different Old Master paintings may be involved. (For a break-down on what we know so far, read “The Frans Hals Forgery Scandal, Explained.”)

Related: Plot Thickens In Dispute Over Seized Cranach Painting

All the paintings appear to have originated with one man, an obscure French collector-turned-dealer named Giulano Ruffini. The works appear to have had next-to-no provenance, save that they came from the collection of French civil engineer Andre Borie. Ruffini insists he never suggested they were the real deal, and that eager dealers were the ones to declare his paintings Old Master originals.

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Venus (1531). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The art world was quick to fall in line, with London’s National Gallery displaying the Gentileschi and the Pamigianino popping up at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. At one point, the Louvre in Paris launched a fundraising campaign to buy the Hals, dubbing it a “national treasure” after it was authenticated by France’s Center for Research and Restoration.

Related: Suspected $255 Million Old Master Forgery Scandal Continues to Rock the Art World

The fact that so-called experts were fooled suggests that connoisseurship, long the gold standard of Old Master authentication?which does not rely on science but a less tangible ability to sense the presence of a great artist’s hand?can no longer be relied upon.

Orazio Gentileschi, David Contemplating the Head of Goliath. Courtesy of the Weiss Gallery.

Perhaps most frightening of all, there is no telling how many fakes still lie in plain sight, accepted as originals by experts and the public alike. Famed contemporary forgers such as Wolfgang Beltracchi and Mark Landis, for instance, have infiltrated many museum collections. In 2014, Switzerland’s Fine Art Expert Institute estimated that 50 percent of all work on the market is fake?a figure that was quickly second-guessed, but remains troubling.

Related: Artist Hides Forgery in Major London Museum

As artnet News continues to follow this developing story, here are just a few of the most high-profile art forgery cases that have come to light in recent years.

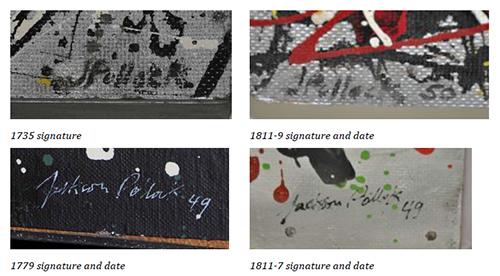

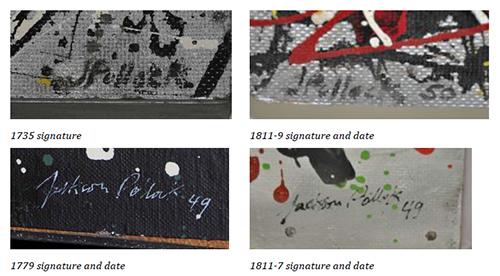

James Martin’s expert report shows the signatures from four Knoedler paintings that were purported Jackson Pollocks. The top two signatures are quite similar. The bottom right signature shows signs that the name was first traced onto the canvas using a sharp tool, and is very similar to the signature on the bottom left, which is misspelled “Pollok.” Courtesy of James Martin.

1. Knoedler Forgery Ring

Glafira Rosales, an obscure Long Island art dealer, her boyfriend, and his brother enlisted Pei-Shen Qian, a Chinese artist in Queens, to paint Abstract Expressionist canvases in the style of such masters as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, and others. The venerable Knoedler gallery, which closed in 2011 as the forgeries came to light, still claims they believed Rosales’s story that the works were part of an undocumented collection sold directly by the artists to an anonymous “Mr. X.”

Related: Knoedler Fraud Trial Settles

Whether or not the gallery was in on the scheme (one of the many claims against Knoedler went to trial earlier this year but was settled before gallery president Ann Freedman could testify), they still sold the worthless works for $80 million, leaving a slew of lawsuits, some still unresolved, in their wake.

Uzbekistan’s State Art Museum, Tashkent. Courtesy of Abdullais4u via Wikimedia.

2. An Inside Job in Uzbekistan

Even possession of an original work of art doesn’t protect you from worry. The Uzbek State Art Museum, for instance, discovered that over the course of 15 years, its collection was systematically pillaged by a group of employees, at least three of whom have since been convicted.

Over 25 works by European artists, including Renaissance great Lorenzo di Credi and modern Russian artists Victor Ufimtsev and Alexander Nikolaevich, were swapped out for copies. The employees then sold the originals on the black market for a pittance.

There are many forgeries of Alberto Giacometti’s Walking Man. Courtesy of Cornell University Museum.