Graham Fagen, “A Drama in Time” (2016) (all photos by the author for Hyperallergic)

EDINBURGH — “Scotland is a canny nation when it comes to remembering and forgetting,” wrote the poet Jackie Kay. This year’s edition of the Edinburgh Art Festival — whose title, More Lasting Than Bronze, was lifted from Horace’s line “I have built a monument more lasting than bronze” — seeks to explore, through seven special commissions, how and what we choose to publicly remember and, perhaps more crucially, what we choose to forget.

Kay was writing in 2007, on the bicentenary of Britain’s abolition of the slave trade. “The plantation owner is never wearing a kilt,” she continued, referencing Scotland’s glossing over of its complicity in slavery. It is a subject that has troubled Graham Fagen for more than a decade and to which he returns in his festival commission, “A Drama in Time.” Five neon panels light up a dark street under a railway track in Edinburgh’s Old Town. Flanking a skeletal figure are two ships, The Bell and The Roselle. These are ships on which, in 1786, the poet Robert Burns booked and then canceled passage to Jamaica, where he intended to take up a job as a bookmaker on a slave plantation — changing his mind only when his poetry found success. This story, Fagen’s work suggests, is part of a cultural history that is normally absent from Scotland’s reverence for its national bard.

Jonathan Owen, “Untitled” (2016)

“A Drama in Time” sits at the bottom of a very steep staircase called Jacob’s Ladder, named after the biblical connection between heaven and earth and separating Edinburgh’s twisting, medieval Old Town from the elegant and well-planned New Town. At the top of the staircase is Calton Hill, home to the National, Nelson, and Dugald Stewart monuments, Athenian-style tributes to the Scottish Enlightenment. But in the Burns Monument we find something darker. Established in 1831, the monument was built to house a statue of the poet, which had to be removed shortly afterward due to smoke damage from a nearby gasworks. Jonathan Owen uses the empty space for his untitled commission. Owen purchased a 19th century marble statue of a nymph and mutilated it, reshaping its torso and neck into a series of interlocked chains and leaving its head to hang as if brutally murdered. The original statue, Owen says in the festival notes, was “made to embody a kind of idealized female modesty and passiveness for the gaze of wealthy men.” Owen breaks that gaze and reveals the cruelty hidden within.

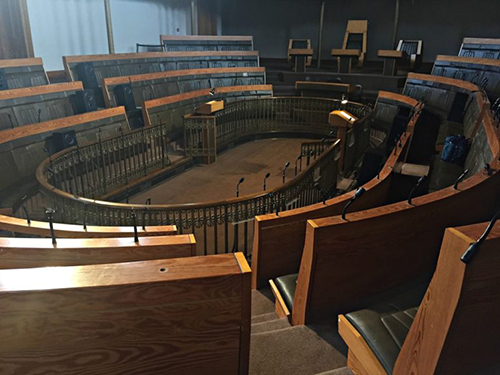

Opposite the Burns Monument is another of Edinburgh’s underutilized grand spaces, New Parliament House. Once the Royal High School, the building was adapted for use as the new Scottish parliament following the devolution referendum of 1979. That referendum failed to pass on a technicality, though, and when a second referendum in 1997 did lead to the creation of parliament, the building was passed over in favor of a brand new structure. In what would have been the debating chamber, Bani Abidi has finally brought voices to a long-silent room. Her sound installation brings to life the forgotten histories of the more than one million Indians who fought for the British in the First World War. Folk songs sung by women in Indian Punjab pleading for their men not to go to war are followed by passages drawn from the censored letters Indian soldiers wrote to their loved ones telling of its horrors and, as Abidi writes in the festival’s notes, their “confusion over whose war they were fighting.” These letters never reached their intended recipients and so for years the Indian soldiers of WWI, when remembered, have been commemorated as having made a noble sacrifice for the Crown, even if their reality was closer to being dragged into a war that wasn’t their own.

“A Drama in Time” sits at the bottom of a very steep staircase called Jacob’s Ladder, named after the biblical connection between heaven and earth and separating Edinburgh’s twisting, medieval Old Town from the elegant and well-planned New Town. At the top of the staircase is Calton Hill, home to the National, Nelson, and Dugald Stewart monuments, Athenian-style tributes to the Scottish Enlightenment. But in the Burns Monument we find something darker. Established in 1831, the monument was built to house a statue of the poet, which had to be removed shortly afterward due to smoke damage from a nearby gasworks. Jonathan Owen uses the empty space for his untitled commission. Owen purchased a 19th century marble statue of a nymph and mutilated it, reshaping its torso and neck into a series of interlocked chains and leaving its head to hang as if brutally murdered. The original statue, Owen says in the festival notes, was “made to embody a kind of idealized female modesty and passiveness for the gaze of wealthy men.” Owen breaks that gaze and reveals the cruelty hidden within.

Opposite the Burns Monument is another of Edinburgh’s underutilized grand spaces, New Parliament House. Once the Royal High School, the building was adapted for use as the new Scottish parliament following the devolution referendum of 1979. That referendum failed to pass on a technicality, though, and when a second referendum in 1997 did lead to the creation of parliament, the building was passed over in favor of a brand new structure. In what would have been the debating chamber, Bani Abidi has finally brought voices to a long-silent room. Her sound installation brings to life the forgotten histories of the more than one million Indians who fought for the British in the First World War. Folk songs sung by women in Indian Punjab pleading for their men not to go to war are followed by passages drawn from the censored letters Indian soldiers wrote to their loved ones telling of its horrors and, as Abidi writes in the festival’s notes, their “confusion over whose war they were fighting.” These letters never reached their intended recipients and so for years the Indian soldiers of WWI, when remembered, have been commemorated as having made a noble sacrifice for the Crown, even if their reality was closer to being dragged into a war that wasn’t their own.

Bani Abidi, “Memorial to Lost Words” (2016)

In Edinburgh, it is often said, there are more monuments to animals than to women. So too, according to Ciara Phillips, are women’s war efforts absent from commemorations of WWI. Phillips sheds light on this history with “Every Woman,” one of four so-called “dazzle ships” commissioned throughout the UK to commemorate the First World War. Under threat from German U-Boats, dazzle ships were designed to distort a ship’s appearance by using contrasting colors and shapes, the majority of which, Phillips discovered, were created by a predominantly female team. Moored in the Leith Docks, Phillips has dazzled the MV Fingal, a former lighthouse tender, with thick strokes of swirling blue, pink, and yellow. At night, her point is emphasized via a message in retro-reflective pigment: “Every Woman a Signal Tower.”

“Understanding versus Sympathy,” Roderick Buchanan’s film on Edinburgh-born James Connolly — a key figure in Ireland’s 1916 Easter Uprising who is commemorated with monuments in Ireland but nearly ignored in his birth town — is screened in a small side room in St. Patrick’s Church, in an area once known as “Little Ireland.” Olivia Webb’s “Lapides Vivi” invites visitors to a series of public choral workshops in Trinity Apse, a 16th century kirk dismantled to make way for a railway then partially reconstructed. Finally, Sally Hackett playfully commemorates the young, notably absent from most public commemorations, with her ceramic “Fountain of Youth” in a small courtyard off the souvenir shop-lined Royal Mile.

Edinburgh in August, with its multiple festivals and military tattoo, heaves with tourist crowds. While inevitably overwhelmed by the bigger and brasher events circling around them — perhaps the only truly monumental work, the pleasing dazzle ship, will inspire festival crowds to pause — the Art Festival’s seven commissions lead you off the city’s well-trodden paths and toward some of its most evocative places and untold histories.