The Candor of the Camera: Nan Goldin’s Ballad of Sexual Dependency

Nan Goldin, Nan One Month After Being Battered, 1984, silver dye bleach print, printed 2008, 15 1/2 x 23 1/8″ (39.4 x 58.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2016 Nan Goldin.

Nan Goldin stares back at the camera with swollen, bruised, bloodshot eyes. Her facial injuries are so severe that the pupil of the right eye disappears in a cloud of intense red. In contrast, she is made-up in red lipstick and dressed up, dripping with jewels and glossy curls. The bluish light of the flash bulb lights up her yellowish brown bruises. A white curtain lurks ominously in the background.

Nan Goldin, Nan on Brian’s Lap, Nan’s Birthday, New York City, 1981, silver dye bleach print, printed 2008, 15 1/2 x 23 1/8″ (39.3 x 58.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2016 Nan Goldin.

The iconic self-portrait of the artist – and its gut-wrenching title, Nan, one month after being battered – is considered by critics, and by the artist herself, one of Goldin’s pivotal works. Taken in 1984, the image defined a turning point in the artist’s life and work as a photographer and marked the end of her long-term relationship with then-boyfriend Brian. It is still a deeply troubling image, as compelling as it is contentious; it is no wonder that it has defined Goldin’s archive. In the publication of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, Goldin writes of the events that preceded it: “For a number of years I was deeply involved with a man. We were well suited emotionally and the relationship became very interdependent. Jealousy was used to inspire passion. His concept of relationships was rooted in … romantic idealism … I craved the dependency, the adoration, the satisfaction, the security, but sometimes I felt claustrophobic. We were addicted to the amount of love the relationship supplied ... Things between us started to break down, but neither of us could make the break. The desire was constantly reinspired at the same time that the dissatisfaction became undeniable. Our sexual obsession remained one of the hooks. One night, he battered me severely, almost blinding me.”

Nan Goldin, The Hug, New York City, 1980, silver dye bleach print, printed 2008, 23 1/8 x 15 1/2″ (58.7 x 39.4 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2016 Nan Goldin.

Yet the image is far from a straightforward condemnation of a violent lover. Goldin did not name her abuser until much later and she did not include any of the images of Brian when The Ballad was originally released. She stated at the time that this was because she intended for the deeply personal image to have universal function – to show that every couple has the potential to combust into fits of passion or rage. The Ballad of Sexual Dependency takes its name from a song in Bertolt Brecht’s Threepenny Opera – in which Mrs Peacham sings about the inexorable sexual power women have over men. Goldin’s operatic photo album is an attempt, as the artist puts it, to figure out “what makes coupling so difficult,” something Goldin searches for in addiction and obsession, love and sex, drugs and violence – wherever the struggle between independence and dependence is present.

Nan Goldin, Rise and Monty Kissing, New York City, 1980, silver dye bleach print, printed 2008, 15 1/2 x 23 1/8″ (39.4 x 58.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2016 Nan Goldin.

The image is also included in the current iteration of Goldin’s slideshow The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – on view at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, until February 12, 2017. While it still provides an emotional underpinning to the work, the photograph also highlights Goldin’s obsessive need to control ways of seeing. When she began showing her portraits in New York in the 1970s, cash was tight and the artist used the slideshow format rather than make expensive prints – but over the years she has added to it and altered it. The soundtracks she developed, meanwhile, evolved naturally from showing her work at bars and nightclubs, where her friends would often suggest music and share in her process of editing. Now the songs are in a symbiotic exchange with Goldin’s visual sequence. The narrative is as rhythmic as it is emotional – a symbiotic exchange that mimics Goldin’s conceptual ideas on the nature of dependency and the flickering, fading heartbeat of life on the edge.

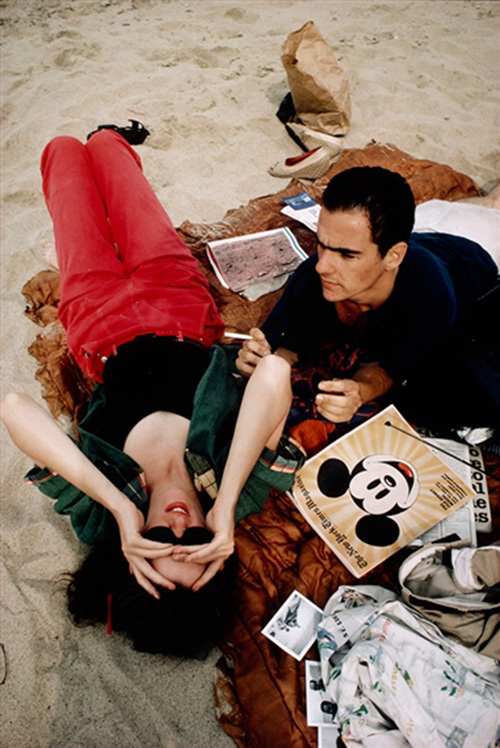

Nan Goldin, C.Z. and Max on the Beach, Truro, Massachusetts, 1976, silver dye bleach print, printed 2006, 23 1/8 x 15 1/2″ (58.7 x 39.4 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2016 Nan Goldin.

Goldin has often emphasized the personal nature of her work – calling it a ‘diary’ – and has insisted on its honesty: “I want to show exactly what my world looks like, without glamorization, without glorification. This is not a bleak world but one in which there is an awareness of pain, a quality of introspection.” Yet there is a design to her work – and a photograph cannot speak, or tell the whole truth. It is always a construction based on perspective. Though Goldin’s photographs present motion and are presented in motion, she sticks with the static: large and lush, she controls the image information, and through the music she employs, guides the way we see and the emotions we feel very precisely. There is not one image out of 700 photographs that make up The Ballad that we are left to linger over more than Goldin wants us to. Viewing the work, fully immersed in her world, gives you a sense of the order she seeks over her environment when she shoots – quite contrary to the content of the images themselves, where lives spiral erratically out of control.

Nan Goldin, Buzz and Nan at the Afterhours, New York City, 1980, silver dye bleach print, printed 2008, 15 1/2 x 23 1/4″ (39.4 x 59 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2016 Nan Goldin.

“Since its inception in the 1980s, and including its presentation in the 1985 Whitney Biennial or the 1986 Aperture publication, The Ballad has remained one of the most celebrated and influential photographic works,” says Lucy Gallun, Assistant Curator, Department of Photography, MoMA. “So we are thrilled, but of course not surprised, by the passionate response of visitors to this current installation. The work resonates on a deep level for many audiences: from those who themselves participated in the downtown club scene or who lived through the height of the AIDS crisis, to those who may not have even been born when many of these photographs were shot; from those who can identify by name the individuals that appear in these images, to those who are experiencing this work for the first time.”

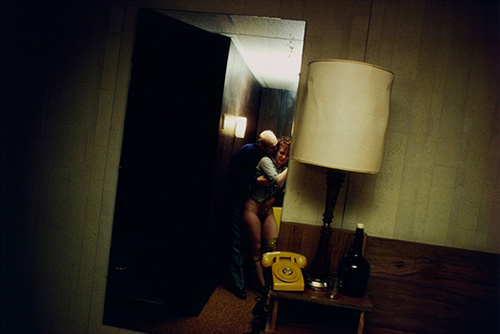

Nan Goldin, Nan and Dickie in the York Motel, New Jersey, 1980, silver dye bleach print, printed 2008, 15 1/2 x 23 1/8″ (39.4 x 58.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2016 Nan Goldin.

The candor of the camera is never easy. Throughout her career Goldin’s ballad for the next generation has been of how we see the private lives of others. Making the invisible visible has been the defining urge of photography, from its inception, but Goldin has inspired many a millennial to turn the camera on their own inner lives, to make their own private story public. Ultimately, in Goldin’s work, photography is about control. Just like in the image of her beaten face, photographs are a way to take ownership of a situation, to edit your own view of the world and create your own memories from which to learn.

—Charlotte Jansen