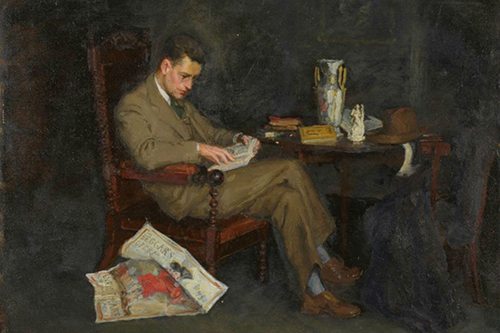

Courtesy of Bryn Mawr College.

Susan Eakins very likely began the painting in her husband’s studio. Unfinished canvasses lay around, so perhaps she chose one — a barely-started half-length portrait of a man, a portrait not in good shape, apparently having lain around a while — and started to paint over it.

At least that’s what might have happened.

Gerrit Albertson is a graduate student at the Winterthur/University of Delaware program in art conservation. He’s actually a second-generation conservator: His mother, Rita Albertson, is the chief conservator at the Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts.

As part of the graduate program, students must study paintings that may have challenges for conservation. Among three paintings he studied in his second year, Albertson got The Bibliophile. It came from Marianne Weldon, collections manager for the art and artifact collections at Bryn Mawr College, where The Bibliophile lives.

Joyce Stoner, a professor in the Winterthur/University of Delaware program, says Weldon also mentioned “there was a legend attached to the painting that there’s an unfinished painting underneath” associated with Eakins.

Albertson went to work, first doing old-fashioned, look-it-up research. He found two sources that said the canvas for The Bibliophile was originally Thomas Eakins’. Alas, those sources give no reasons or references; they just say so.

At first, Albertson was skeptical. But then he noticed something in crossways light.

He writes by e-mail from Naples, where he is working this summer: “[I]f you look closely at the surface of the painting, you can see ridges of paint that don’t correspond to the Susan Eakins portrait on top.” Electron microscopic analysis of a tiny cross-section suggested that different white pigments had been used in the top and bottom layers of the canvas — “which could suggest two different artists were at work.”

Here, he ran into a roadblock.

The restorer used by Susan Eakins applied a lead white lining adhesive to the back of the canvas, blocking all attempts to make an x-radiograph. So x-rays were useless. What to do?

Albertson went for gold. He contacted John Delaney, senior imaging scientist, and Kate Dooley, research scientist, at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. The gallery has spectroscopic instrumentation that allows for the noninvasive examination of paintings. Depending on the materials present and the layering structure of the painting, sometimes visualization of subsurface paint layers is possible.

Delaney suggested that they try hyperspectral reflectance spectroscopy in the reflective near-infrared range. (Stoner calls this kind of analysis “very, very sexy and hard to arrange.”) They employed their novel, near-infrared spectral imaging camera, developed in part with George Washington University, to collect more than 500 images of the painting at different near-infrared wavelengths. Albertson calls them “tremendously kind and generous with their time. … I couldn’t be more grateful that they were so willing to help a student out with his project.”

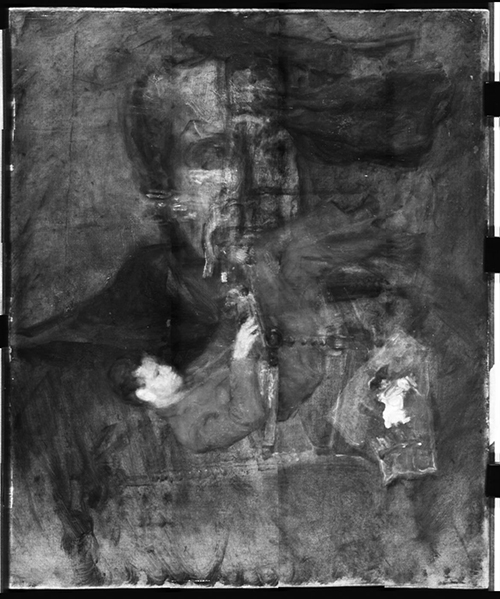

What they come up with appears in the images below.

Beneath the seated reader, there is an unfinished, sketchy-looking painting of a half-length male figure. The head is clearly visible in the spectroscopic images. Here is an unenhanced image from the National Gallery analysis:

Courtesy of John Delaney and Kate Dooley, National Gallery of Art.

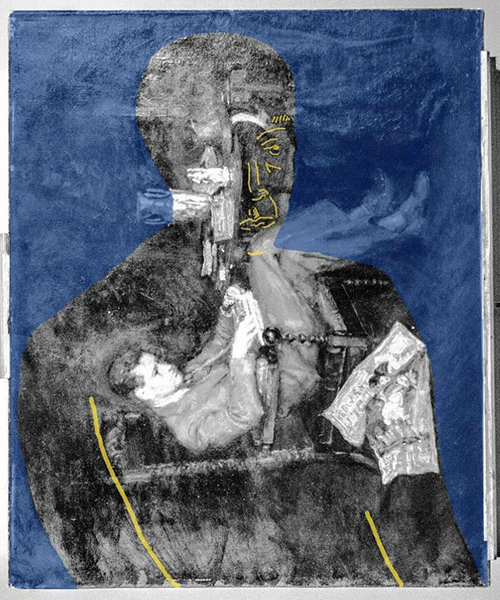

Here is an infrared image on which Gerrit Albertson drew the outlines of what he thought he was seeing in the first place, with the background blued and lines inserted to suggest where facial and bodily features might be:

Courtesy of Gerrit Albertson, Winterthur/University of Delaware program in art conservation.

Exciting. But Albertson went further. At the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C., at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, and at Bryn Mawr, he examined some old palettes - the wood boards on which painters mix their colors - associated with or once used by Thomas Eakins. Albertson analyzed the paints, and they corresponded pretty well to the paints in the lower layers of the canvas.

And he found that the specific white pigment Eakins used was different from the white his wife used. And guess what? Her white is found in The Bibliophile, while his is found underneath.

So … what do we have? A circumstantial case. We have the legend; those two citations that say the underlying painting is his; and the differences in paints suggesting two painters, with the whites used on the bottom layers being like Thomas’ whites and the top whites being someone else’s, presumably Susan but not Thomas. We also have Susan working in Thomas’ studio and using someone’s old painting, which had been hanging around a while unfinished.

Was Albertson's work persuasive to his professional peers?

He presented his findings to a meeting of the Association of North American Graduate Programs in Conservation at Harvard University this April. Stoner calls this a “highly critical group ready to tear us apart if we go outside the bounds of exactitutde, and they loved his work and had no doubt.”

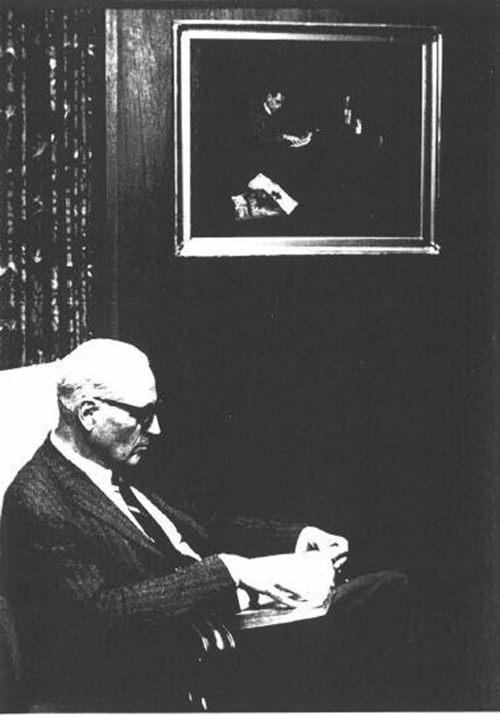

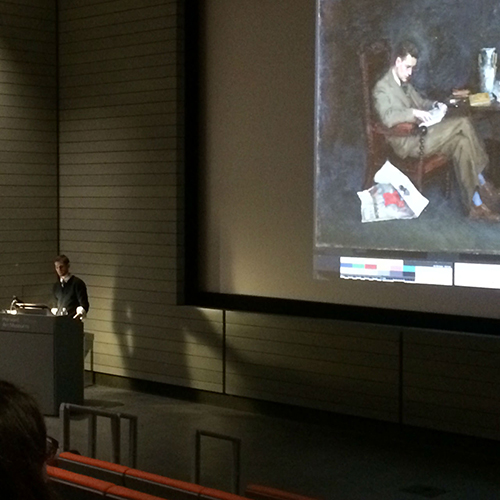

Gerrit Albertson reports on his findings to the annual meeting of the Association of North American Graduate Programs in Conservation at Harvard University in April. On the screen is Susan Macdowell Eakins' The Bibliophile with a color bar beneath it. Courtesy of Joyce Stoner.

Nice — but it isn’t proof. Albertson e-mailed a hyperspectral reflectance image to Kathleen A. Foster, an Eakins scholar and senior curator of American art and director of the Center for American Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art — and “she did not feel comfortable making an attribution based on this image alone.”

Neither does Albertson: “I can only say that I wouldn’t rule Thomas Eakins out.”

How can we ever know for sure? Maybe we never will, says Albertson — unless some more certain link surfaces somewhere. Albertson writes that there is “no substitute for closely looking at an actual painting.”

And unless we were to wash away Susan's painting, and erase The Bibliophile completely, that is something we probably never can do.