'It was not a sentimental love': Françoise Gilot on her years with Picasso

At 94, the artist talks to Emma Brockes about her unlikely match with Picasso, her own ambition – and why she’s buying back all her paintings

Françoise Gilot at home in New York City. Photograph: MARC_SCHUHMANN/Ana Lessing

Emma Brockes@emmabrockes

Friday 10 June 2016 12.00 BST

Françoise Gilot takes a stern line with interviewers, assuming they approach her with interest in only one thing: her affair with Picasso, which started 70 years ago and lasted a decade, during which time she had two children with the artist, before walking out. “When people know nothing about you except one thing, you have to talk about that,” she says, looking, at 94, much younger than her age. In the early stages of our encounter, she repels every question with “Certainly not!” and “I don’t know why you think that” as if observing a formal phase of the interview in which all prior knowledge about her must be denied. Then, just as abruptly, her fierceness subsides. “That’s the way it is,” she says, of my misapprehensions, and bursts into peels of laughter.

In fact Gilot will talk expansively about Picasso, but not until she has established him as a single element in a remarkable life, evidence of which can be seen around her apartment, a huge, barrel-ceilinged space in upper Manhattan where Gilot’s paintings hang on every wall. We are half a block from Broadway, but no sense of the contemporary world creeps in. When coffee is served, in fine china and on a trolley wheeled in by a housekeeper in uniform, there is a sense we could be meeting at any point in the last 100 years. “My life is exactly the same here as it is in Paris,” says Gilot. “I live my own life in my own way. It doesn’t matter where I am.”

Pablo Picasso and Françoise Gilot with Picasso’s nephew on the Côte d’Azur in 1951. Photograph: Robert Capa/Magnum

The irony is that, for most of her life, Gilot has been waiting for the world to catch up with her. She has always pointed out that it does her a great disservice as an artist to identify her as “Picasso’s lover” or “a friend of Matisse”. Gilot was born in Paris, the only child of a wealthy industrialist father and an artistic mother who raised her with the same expectations they would have had of a boy – although this doesn’t entirely explain her attitude. Rather, she seems to be one of those people who emerge out of time and space, untroubled by their generation’s anxieties. It is a mark of how, for women, these anxieties linger on that when she talks about her talent without shame or apology – “I was considered astonishingly good” she says of herself as a young artist – it is still a little shocking.

Gilot is used to shocking people. She remembers the first time she did it, when she was five years old and had already started going to the Louvre with her teacher. That same year, while on holiday in the Alps, she pointed out some aspect of the landscape to her father. “I was struck by the fact that, at a certain altitude, there were a lot of dark grey trees, mostly firs, and also meadows of a lively green. And I thought those two colours together were interesting. So I asked my father, ‘When you look at that, as I do, do you see the same thing?’” Her father was immensely irritated by this remark. “He said, ‘Oh, how ridiculous, the retina, blah blah blah, it looks the same for everybody.’ I said that is not exactly what I meant, but I did not know how to say it. It was not the instrument of seeing, it was the result in my psyche. The feeling! At five years old, I could not ask the follow-up question.”

Her mother, Gilot says, would have understood what she was driving at. She was “a typical artist’s mother” in that she encouraged her daughter to have the career she had herself been denied. Gilot’s mother was a gifted ceramicist, with a fantastic knowledge of art history. Nonetheless, one gets the impression it is her father with whom Gilot identifies. He was an uncompromising figure, a wilful man who, during the 1940s, refused to collaborate with the Nazis and was not at all keen on his daughter becoming an artist. “He thought I should have been a physicist, but I refused completely. I said, ‘My imagination is not in it.’ I said ‘Philosophy’ and he said, ‘No!’ I said, ‘OK, the law.'

Runaway Comet (1998) Photograph: Ana Lessing

Gilot started law school in her late teens, but before she could graduate, the Germans invaded Paris. She was briefly detained by the French police for the political act of laying flowers on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. As a result she was put on a list of agitators, some of whom were later executed by the Germans. For a while, Gilot had to go the police station every day and sign a form, something she now thinks was a ploy to intimidate her father. It didn’t help that she was a law student. “The Germans detested French people studying the law.” And so she dropped out, ostensibly for security reasons, but really, she says, so she could start her life as an artist. “At the same time as I found a way out, I found a way in. Which is typical of me. To make in one move what is in fact a double move.”

Gilot crosses the room to a stack of canvases, which she starts heaving around, shooing me off when I try to help. Eventually, she finds it: a line drawing that she did when she was 12 years old, copied from a plaster cast in a museum. What’s striking is not how good it is, but how adult, a solemn, brooding depiction of a man; not a child’s drawing at all. Gilot never cared for it, she says, which is how it remains in her possession. When the Germans invaded, her mother sent away a cart-load of precious items from the house, including Gilot’s favourite paintings, and the cart crashed, destroying its contents. She shrugs. “All my early work disappeared. It doesn’t matter, because I had done the work and had the experience.”

'‘He said, nobody leaves a man like me. I said, we’ll see’'

But that’s not the point. The point is, “I knew how to draw. I was never an amateur in what I did. As you see, I knew about third dimension and all that. I was very much at ease.” Presumably, she didn’t yet know what she wanted to say as an artist? Gilot looks indignant. “I always knew what I wanted to say, it was how to say it.”

And then came Picasso. They met in a cafe in 1943, when Gilot was 21 and Picasso was over 60. Gilot had been making a name for herself at art school and her work was already selling. This is one of her bones of contention with her artist peers; that so many of them are hopeless about business. Not Gilot. “It comes from my father saying you have to be professional. I had no choice. And I must say, I owe him a lot. He said he wanted to put lead shoes on my feet, so that I wouldn’t float away. The result has been that I was capable of understanding the whole problem [of money].”

And your parents didn’t assume, as was the norm, that you would be an artist for a few years and get married?

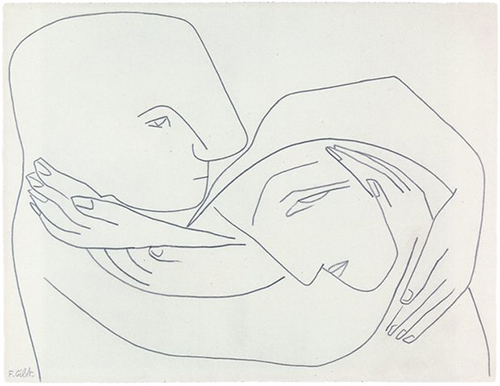

The Kiss (1948) Photograph: Ana Lessing

“They never thought that. My father’s mother had lost her husband rather early, she was a widow with five children and had a good brain too, so it was OK. But my father had a sense of catastrophe. It was at a time when catastrophe was all around, with Hitler. And so I had to prove myself as a boy, and be responsible for myself. Which I did. I was never indulged as many girls are. Not in anything. I remember I was a rather good horse rider, and I came in one day and said ‘I’m very pleased, I jumped this high.’ He said, ‘Raise the bar!’” It sounds as if his approach suited her temperament. “I am exactly the same!” Gilot claps her hands with joy. “I have to admit! It’s rather funny.”

When, that first evening in the cafe, Gilot told Picasso she was a painter, he said “That is the funniest thing I’ve ever heard. Girls who look like you could never be painters.” Their relationship was, in the first instance, a great intellectual friendship, which had it not been for the war, she thinks would probably never have bloomed into romance. “Because I would have thought he’s very old, I’m very young. The men who could’ve been interested in me, and me in them, just disappeared. It was not a time like any other. It was a time when everything was lost; a time of death. So: do I want to do something before I die, or not? You have to seize it. It was – let’s do something right away!”

Even Gilot’s parents were not that liberal, and so to begin with she concealed her involvement with Picasso, who for the entirety of their relationship was married to Olga Khokhlova. After a few years, Gilot moved in with him and they had two children, Claude and Paloma. I ask Gilot if it was a very passionate relationship and there is a long pause, after which she assumes a rather naughty expression. “Eventually,” she says. “But, you know, it was not what we call in French l’amour fou! Non! It was an intellectual dialogue as well. I could not say that it was a sentimental love. It was maybe an intellectual love, or a physical love, but certainly not a sentimental love. It was love because we had good reason, each of us, to admire the other.”

Was it restrained by the fact you were both protecting your art?

“No.” She thinks for a moment. “My taste in men is in long, narrow, six foot or more, and Picasso was the exact opposite. He was smaller even than myself. And I’m very small. He was not my type, physically. It was because we had so many things working together that made us compatible. But otherwise – age-wise and in lots of other ways, we were not compatible.”

She judges that, if she had never met him, Picasso’s influence on her work would have been precisely the same, because she had studied his work. “On the contrary, because I was there, I had a tendency to retract a little bit.”

Photograph: Ana Lessing

Surely, being involved with an artist of that magnitude threatened to overwhelm her own style and development? No, says Gilot. “In art subjectivity is everything; I accepted what [he] did but that did not mean I wanted to do the same.”

Didn’t love interfere with all that? A slow chuckle. “Love interferes with everything.” But weren’t you in danger of losing yourself – your central vision? There is a long, long pause. “Why?” Because you had to give so much of yourself. “Yes, but the heart is on the left, and the brain is on the other side.”Gilot considers. “You might say that I am a little bit hard-boiled. I have to admit that I was never so much in love with anyone that I could not consider my own plan as interesting. It’s a bad idea that women have to concede. Why should they? That was not for me. Probably I was a bit ahead of my generation.”

She was also, by her own admission, something of a tactician. She studied Picasso intently but, she says, “He did not know me well at all. I am very secretive. I smile and I’m polite, but that doesn’t mean that I am in agreement, or that I will do as I said I would do. It’s just a screen. He thought I would react like all his other women. That was a completely wrong opinion. I had other ideas. I did not put my narcissism in being represented by him. I couldn’t care less.” When Picasso painted her, she asked that he call the painting, “Portrait de Femme” rather than using her name. As he became increasingly cold and tyrannical, she thought about leaving. It took her two years to come to a final decision. Was there anything that would have made her stay?

“I wanted a bit more affection, maybe; not love, but affection. So anyway, I was not satisfied.” She laughs, but it was a bitter ending and after she left, they were estranged, meeting only once more a year later, when she handed over the children for a visit. I ask her if leaving him was liberating.

“No, because I was not a prisoner. I’d been there of my own will and I left of my own will. That’s what I told him once, before I left. I said watch out, because I came when I wanted to, but I will leave when I want. He said, nobody leaves a man like me. I said, we’ll see.”

Landscape for a Gold Digger (1971) Photograph: Ana Lessing

In the years after Gilot and Picasso broke up, he tried to ruin her, bad-mouthing her across the whole industry. “So what!” she says. “I would have been quite stupid to expect something else. In life, you have to measure ahead of time, otherwise you are stupid. You have to measure the quantity of danger that you can afford. You know? If I had not thought I was up to it, I would not have done it. I would have stayed.”

Gilot moved to America to try to escape Picasso’s orbit and, in spite of him, her work kept selling. In 1970, she married Jonas Salk, a pioneering scientist who invented the first polio vaccine, and remained with him until he died in 1995.

She has always made a living from her art and these days often bids on her own work – she is trying to recover as many paintings as possible; she likes to bring them home. Often she can’t afford it; when auctioned at Christie’s and Sotherby’s, Gilot’s paintings can go for upwards of $100,000 (£68,000).

On an easel in the centre of the room is a painting she recently bought back, that she painted in London in the 60s. It is a typical Gilot to the extent that it combines the figurative and the realistic, depicting collapsed columns from Greek mythology with a bird of prey bearing down on them. “What happens in everyday life is being attacked by a hawk,” she says, “which means that every day, there is destruction and construction. I call it Past Present. You might think there is something a little philosophical about it.”

Le Coup de Telephone (1952). Photograph: Ana Lessing

She continues to paint every day, quickly, as she always has. “I am not like the painters who fiddle around.”

When has she come closest to defeat?

“To defeat? Every day of my life. That’s true. I also come close to success. It is the same. Fifty-fifty.”

She is so fierce and uncompromising, that, as I get up to leave, I wonder aloud whether Gilot derives energy from opposition. No, she says. It is, rather, a question of being able to confront the bad as well as the good. “You have no choice. That’s the way it is. So non, non, I don’t like to fight.” She gives me a challenging look, spiked with merriment. “But if I have to, I will.”

• The Woman Who Says No, Francoise Gilot on Her Life With and Without Picasso by Malte Herwig is published by Greystone. To order a copy for £14.39 (RRP £17.99) go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99.

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/jun/10/francoise-gilot-artist-love-picasso#img-1