Amid a Challenging, Changing City, SFMOMA Reopens with Global Aspirations

The new San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s 3rd Street atrium entrance (all photos by the author for Hyperallergic)

SAN FRANCISCO — After a three-year closure, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) reopens to the public on May 14. The museum is a new institution, thanks to an enormous new wing and the acquisition of the whopping Doris and Donald Fisher Collection. It opens at a time of new museum practice. Like more and more large museums around the world, SFMOMA wants to serve a global audience with “culture,” not just art.

The museum is also opening in a city that has become even more of a congested, fractious, global economic power — with the problems to match. The ultimate success of the new museum will depend on how well it balances these conflicting concerns.

An Alexander Calder sculpture by the “living wall” (click to enlarge)

The museum kept its 1995 brick-and-cylinder building by Mario Botta and hired the Norwegian firm Snøhetta to build a tall, white wing behind it. The new building is an elegant iceberg floating behind Botta’s sturdy fortress. It’s a dense site, and the Snøhetta team made the extension feel seamless. The extension slots right into its narrow space like it’s always been there, and the new galleries line almost exactly with the old. The most special addition may be the third-floor “living wall.” Covered with 19,000 plants, it’s the largest green wall in the US, and it’s going to delight every adult and child who steps out of the Alexander Calder room.

While the effect of the Snøhetta extension is delicate, its impact is big. It adds 230,000 square feet to the museum and triples the gallery space. The previous building had four gallery levels, wide-open spaces, and lots of natural light. Visiting used to be a casual, two-hour affair. But the new museum launches with 1,900 pieces spread over seven gallery levels. And while lead architect Craig Dykers was eager to talk up all the ways he’d sought to add “palate cleansers” and “intimacy” with varying stair heights, light screens, and alcoves, there’s no getting around it: walking through the museum now requires all-day stamina and commitment.

Between the museum’s permanent collection, the Fisher Collection, and a new modern and contemporary initiative called the Campaign for Art, the SFMOMA team has combined three different institutions into one massive building. The original permanent collection, still on view, is strong on photography, reasonable on contemporary, and has a smattering of 20th-century European and American modern art. With the Fisher Collection, the museum now also has a Manhattan-centric greatest hits collection from the last several decades. The Fishers amassed deep collections of work from artists including Richard Serra, Alexander Calder, Anselm Kiefer, Andy Warhol, Sol LeWitt, Frank Stella, Ellsworth Kelly, and Agnes Martin.

The new SFMOMA facade

The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s new entrance on Howard Street

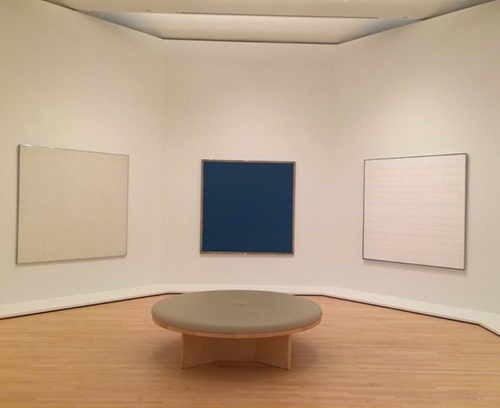

The Fisher Collection’s list of artworks is impressive and so is the museum’s layout. Dedicated, single-artist rooms allow the artists’ strengths to shine. Warhol’s crucial early 1960s silkscreens and Kelly’s razor-sharp colors especially benefit from isolated treatment. Martin, whose sublimely subtle works could’ve been lost amidst the other artists’ noise, has a splendid hexagonal space that reminded me of a nest, or a chapel. But the Fisher Collection is short on all kinds of diversity: gender, race and ethnicity, geography. The danger is that it may dominate the museum’s exhibitions for years to come.

The Campaign for Art seems to be museum director Neal Benezra’s response to that possibility, and it’s where you’ll find the museum’s best surprises. The Campaign celebrated the expansion by securing more than 3,000 works from hundreds of donors. Benezra and his team had fun, securing more adventurous choices from contemporary artists including Ana Mendieta, Tom Marioni, Martha Rosler, Martin Kippenberger, David Hammons, and Nicole Miller. Their list is far more diverse, and it feels more current. However, the lack of current work from Africa, Latin America, and Asia is startling and would be a natural place for the museum to grow.

A window showing the two “seams” of the old and new buildings

It may take the museum’s expanding team (more than a hundred new front-line hires) a little time to settle in. The photography exhibitions are crowded, and some of the original departments, like graphic design, will need new anchors in a collection that’s suddenly grown so rich with paintings and photographs. (The graphic design exhibition Typeface to Interface is promising but lacks the focus of the other galleries.) But the galleries are well designed, and the new works offer a wealth of direction. The key will be clarifying the museum’s vision so it matches the new direction — contemporary art since 1960, not the modern period.

Christopher Wilmarth, “Days on Blue” (1974–77), from the Fisher Collection

The other key will be retaining SFMOMA’s role as a grounding institution in a city that’s facing a full-blown identity crisis. There’s been lots of local hand-wringing about the new museum. Many of the concerns are reflections of how residents feel about San Francisco itself. San Francisco’s recent flood of tech startups and venture capital has washed away its artists and its moderate-income, ethnically diverse neighborhoods. With the museum’s $610 million total price tag, its boosted ticket price ($25, $7 more than when the museum closed three years ago), its interpretative selfie station (a glorified photo booth), and its new restaurant run by the three-Michelin-star chef Corey Lee (whom Benezra calls the museum’s “curator of food”), the new SFMOMA has elements that make it a brash match for an arriviste city.

The city’s journey can be traced through the institution’s own real estate. One of the newly acquired photographs, “South of Market” (1976) by Michael Jang, shows what the neighborhood looked like long before SFMOMA moved into the Botta building: parking lots and desolate streets. Now Larry Gagosian and John Berggruen are preparing to open outposts of their international galleries across from SFMOMA’s blue-chip treasure chest.

Installation view of pieces mostly from the Campaign for Art

The museum isn’t responsible for exacerbating San Francisco’s problems, and it’s trying to address them. Admission will be free to everyone under the age of 18. There’s a goal to triple the number of visiting schoolchildren, from 18,000 to 55,000. In a city that’s lost its young artists and is struggling to maintain its local galleries, the museum is proudly showing off acquisitions from Bay Area artists. There are excellent paintings from Richard Diebenkorn and Wayne Thiebaud, a small but powerful exhibition room for Bay Area conceptual art, and strong offerings in the photography collection (Jang, Irene Poon, Benjamin Chinn, and others, plus a selection of prints from Jim Goldberg’s astounding Rich and Poor series).

There’s only so much one museum can do — especially when it needs to balance a community’s needs with its own. SFMOMA needs a piece of the new money that’s in town, and it needs to get bodies in the door (the museum’s looking to increase attendance to 1 million people per year, over a previous high of 650,000).

Twice the size and seven storeys high: the new San Francisco Museum of Modern Art is ready for lift-off

Galleries filled with blue-chip gifts plus highlights of the Fisher Collection will greet visitors when museum reopens

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art's new wing. © Henrik Kam

Few museum expansions in recent memory have been as anticipated as that of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMoMA). The city's major Modern art museum is due to reopen on 14 May having doubled in size, tripled its gallery space and added 3,000 gifts to the collection, more than 600 of which are on show across 18 inaugural exhibitions. By many measures, the museum is now the largest space dedicated to Modern and contemporary art in the US.

The $305m extension, which has been designed by the Norwegian architects Snøhetta, towers over the institution's original Mario Botta-designed building. Together, the two offer a whopping 170,000 square feet of galleries—26% more than the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

The new facility includes the museum’s first dedicated gallery for works on paper, a new photography centre and a conservation studio. Gary Garrels, SFMoMA's senior curator of painting and sculpture, says he lost five pounds during the installation process from all the walking.

In a presentation to press yesterday, 28 April, Charles Schwab, the chairman of the museum’s board, said: “Today, people’s lives are about sharing, and we wanted a museum that would embrace that spirit.”

This spirit is evident in more ways than one. The inaugural installations are dominated by recent gifts and long-term loans. The new building also has its share of Instagram bait to encourage social media sharing. There is a “living wall” of native California plants designed by the local firm Habitat Horticulture; outdoor terraces with sweeping city views; and a new lobby gallery for large-scale installations that is free to the public. It opens with Richard Serra’s 213-ton steel sculpture Sequence, 2006.

Richard Serra’s Sequence (2006) at SFMOMA. © Henrik Kam. Courtesy of SFMoMA.

Snøhetta's seven-storey addition boasts a rippling façade whose aesthetic is part Christo, part Apple store. The architects say they were inspired by the gentle waves on the San Francisco Bay. Inside, however, they aimed to make the architecture serve the art and the museums' visitors.

Imperceptible touches encourage visitors to dwell in the museum. To prevent them from getting tired too easily, for example, the staircases between the lower floors are less steep than those on the higher floors. To foster quiet contemplation, the ceilings are lined with soundproof plaster and filled with crushed glass beads.

But the star of the new display—for better or for worse—is the collection. “When we opened [the Botta building] in 1995, the museum was quickly given over to exhibitions,” SFMoMA’s director Neal Benezra says. “We wanted to redress that balance and focus on the collections.” High-impact gifts on show at the museum for the first time include Ed Ruscha’s Smash (1963), purchased by Schwab at auction in 2014 for $30.4m, and a room full of late photographs by Diane Arbus.

The largest and most talked-about inaugural exhibition presents 260 highlights from the collection of Gap clothing store founders Donald and Doris Fisher. The blue-chip collection of more than 1,100 works of US and European (mostly German) art, on loan for 100 years, was a major factor in the museum’s decision to expand. For years, the works have been displayed behind closed doors at Gap’s headquarters in San Francisco, rarely seen by the public.

Under the agreement, the Fisher Collection must be shown together for the first year and then again once every ten years; in between, it can be integrated with the rest of the museum’s holdings. Benezra sees the arrangement as a “new model” that may inspire other museums and collectors. Bob Fisher, one of the couple’s sons and the president of the board, said it would be up to future generations to decide whether to make the loan permanent.

The Fisher display is organised monographically to show off the depth of the collection, which includes nearly 130 works by Sol LeWitt, 45 by Alexander Calder, 41 by Ellesworth Kelly and 24 by Gerhard Richter. (Doris Fisher used to speak with Kelly by phone every few weeks.) An octagonal room with seven paintings by Agnes Martin is fondly referred to as the “Martin chapel”. The Calder gallery was specially designed with low ceilings to recreate the feeling of seeing the work in a domestic space.

Gifts are the unifying factor behind the majority of the inaugural displays in the new building, including focused galleries on Bay Area conceptual art and new media pioneers including Nam June Paik and Lynn Hershman Leeson. This organising principle may frustrate visitors looking for a more coherent, compelling narrative or for new discoveries by overlooked artists, particularly women and artists of colour. Benezra acknowledges the museum still has “work to do” to further broaden its collection beyond marquee names.

Meanwhile, a few smaller exhibitions like the photography-focused About Time—which mixes older work and new gifts and spans early daguerreotypes to contemporary photographs by Zoe Leonard and Dawoud Bey—show what curators can do when their hands are not tied by commitments to donors.

For his part, Garrels is already looking ahead to mixed presentations of Fisher and non-Fisher work. He is planning a show of double portraits that will juxtapose David Hockney’s 1974 painting of the artists Shirley Goldfarb and Gregory Masurovsky from the Fisher Collection with works including Frida Kahlo’s famous 1931 portrait of her and Diego Rivera and Alice Neel’s portrait of the artists Geoffrey Hendricks and Brian Buczak (1978). “This is the fun part,” he says.

• For further analysis and an in-depth look at the new SFMoMA, see our June issue.