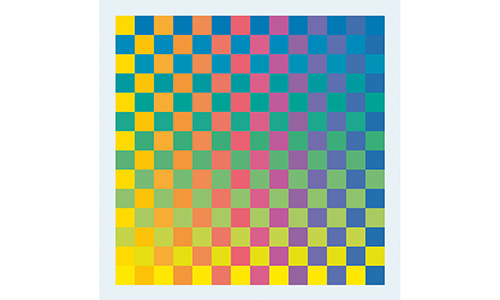

Karl Gerstner, Color Spiral Icon x65b, 2008. Acrylic on aluminum, diameter 41 in. (104 cm). Collection of Esther Grether, Basel, Switzerland.

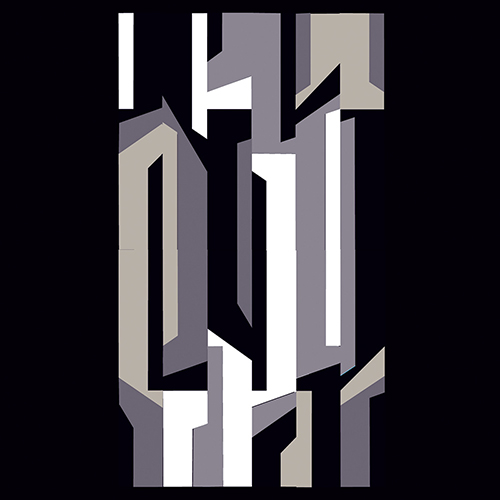

Scientists further confirmed that the laws of nature, such as the force of gravity and the speed of light, are symmetrical in the sense that they apply equally throughout the Universe. These discoveries found widespread application, even inspiring some artists to create iconic expressions of nature’s symmetry in their art. They’d learned of Einstein’s cosmology from popularisations such as Einstein’s own Relativity: The Special and General Theory, A Popular Exposition (1917). Karl Gerstner, a young artist in the 1950s and a leader of this new movement, expressed the impossibility of a single human point of view in the artwork Aperspective: 12 black and white units fixed to magnets, which can be repositioned endlessly within a fixed framework – like light moving through Einstein’s cosmos as a bounded infinity.

Gerstner’s work is in the tradition of Swiss Concrete Art, which was founded in Zurich in the 1930s and ’40s by Max Bill, Camille Graeser, Richard Paul Lohse and Verena Loewensberg. Zurich was a place where physicists and mathematicians, including Einstein, Andreas Speiser and Hermann Weyl, gathered to give a unified description of the forces of nature: gravity, electromagnetism, the strong nuclear force and the weak nuclear force. They used the mathematics of group theory to describe symmetry, which is the property of remaining unchanged when certain operations are carried out. For example, imagine drawing a line down the centre of a person from head to toe, dividing the body into left and right sides. If the person does a half turn (180 degrees) and then a full turn (360 degrees), the body’s silhouette does not change in these two positions because it has left-right (or ‘mirror’) symmetry. In the language of group theory, the body has twofold rotational symmetry about one axis.

Karl Gerstner, Aperspective 1: The Endless Spiral of a Right Angle, 1952–56. Synthetic resin paints on 12 Plexiglas panels, 3 ½ × 17 ¾ in. (9 × 45 cm) ea., secured with magnets unto iron over a base of black Plexiglas, 39 3/8 × 39 3/8 in. (100 × 100 cm). Courtesy of the artist.

The most symmetrical form is a sphere, where all points are equidistant from a point in three-dimensional space. A sphere has an infinite number of axes through its central point, and it remains invariant when rotated to any degree, on any axis. In the late 20th century, scientists concluded that the Universe began in perfect symmetry as a point that exploded into a sphere of plasma. As the infant Universe expanded, the primordial sphere cooled, and matter condensed from the plasma to form the first particles, then atoms, gas clouds and stars. At some point, the original symmetry of the Universe was broken; the resulting asymmetries appear to be the result of random shifts analogous to mutations during evolution. Today at CERN (the European Organization for Nuclear Research) on the French-Swiss border near Geneva, physicists are recreating samples of this primordial spherical plasma to determine the degree to which the Universe retains traces of its original symmetry. Nearby in Basel, a 78-year-old Gerstner created a series of Color Icons (2008) to symbolise the symmetry of nature in the tradition of Swiss Concrete Art.

https://aeon.co/opinions/how-physics-and-maths-helped-create-modernist-painting