NEWS

Paris’s Art Models Protest for Job Security and Better Wages

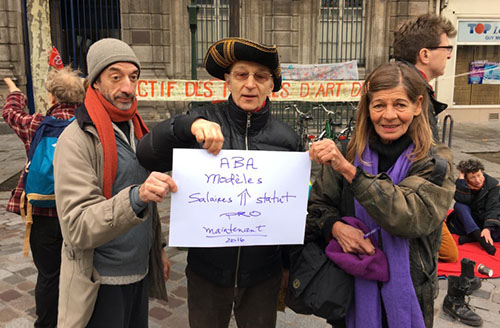

Members of the Collectif des Modèles d’Art de Paris demonstrate in the Place de l’Hôtel de Ville. (all photos by the author for Hyperallergic)

PARIS — On Saturday afternoon, people trickled across the large plaza in front of the Hôtel de Ville. Pausing to admire city hall’s façade, some snapped pictures while others gathered around a group of break-dancers before shuffling off. Meanwhile, tucked away in a far corner of the plaza, an eclectic group was hanging painted banners that read “Modèles” (“Models”), “Modèles d’art: Poser c’est un métier!” (“Live modeling: it’s a job too!”), and the name of their organization, Collectif des Modèles d’Art de Paris (Art Models Collective of Paris).

A Collectif des Modèles d’Art de Paris sign at Saturday’s protest

“In France, live models who pose in fine art studios for painters and photographers do not have professional status,” explained Patrick Bellaiche, a delegate from the cultural workers union Force Ouvrière‘s section for art models and the protest’s organizer. Paris considers Bellaiche and others in his profession to be vacataires — “temp workers” who are employed for short periods, usually less than a day at a time. For these models, attaining professional status would offer

the right to negotiate working conditions and a raise in their minimum wage from an average of €17.40 (~$19.16) per hour to €21.78 (~$23.99) per hour before taxes. Paris’s live models first began to organize in 2008 after a municipal

labor reform outlawed their cornet, the tips traditionally gathered from art students at the end of a drawing session. “When we lost the cornet, we also lost a third of our income,” Bellaiche said. In response to the city’s action, on December 15, 2008, models protested nude in front of the Department of Cultural Affairs. “It was less than three degrees Celsius

outside,” remembered Bellaiche. “And because of that, perhaps, there were many more people who showed up to see us [in 2008] than there are today.” Ever since this nude protest, the models have protested clothed, feeling that the stunt had gotten people to see them but not hear them.

Members of the Collectif des Modèles d’Art de Paris demonstrate in the Place de l’Hôtel de Ville with a sign calling for professional status and salaries.

Indeed, at the heart of their battle for professional status is another, more abstract desire for their trade to be recognized for its historically vital role in the education of young artists. “Models first arrived at the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in 1648,” explained Pascale Nicolas, who was participating in her first protest despite having modeled for four years. “So our trade, in its current form, has existed for 368 years; it would be nice if we could finally be considered as something other than ‘temps.’” Drawing from the nude was central to the training programs of art academies from their inceptions in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. In her essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”

art historian Linda Nochlin explains how academies that forbade women from studying the nude figure were a major impediment to those women’s artistic aspirations. To be deprived of this training meant being deprived of the possibility of creating major art. Fabrice Balossini, a Paris-based artist who came to the protest in search of live models for his own studio practice, confirmed that “we can never really have an understanding of what the human body is like until we have drawn from a live model. The practice is irreplaceable.”

Members of the Collectif des Modèles d’Art de Paris stage a life drawing session in the Place de l’Hôtel de Ville.

Modeling is difficult work, Bellaiche noted. “You don’t get to just sit your butt on a little stool with a book while people draw you, no!” he exclaimed. “Modeling requires endurance, discipline, imagination, and an understanding of body language. You have to love playing with your body in space and to be mindful of the audience drawing you. Are they in front of or behind you? That is what makes the drawings happen.”

Members of the Collectif des Modèles d’Art de Paris stage a life drawing session in the Place de l’Hôtel de Ville.

Despite the grueling nature and modest compensation, models find their work rewarding and validating. Nicolas attributes this to the inclusiveness of the profession: “In live modeling, all morphologies are drawn — young, old, beautiful, ugly, fat, thin. There are no physical barriers to becoming a live model. Quite the contrary.” Although the work draws models from all walks of life, “it seems that a lot of them come from theater or dance backgrounds,” observed Laure Saffory-Lepesqueur, a graduate student in art history at the École du Louvre. After learning about the protest on Facebook, Saffory-Lepesqueur came to see how the conditions of live models today compared to those of women modeling in the 19th century, the subject of her master’s thesis. Her conclusion: “Little has changed.” Bellaiche, on the other hand, sees progress in the campaign. “At the beginning, the Mayor of Paris [Anne Hidalgo] was a wall. In one ear and out the other,” he said. “We couldn’t get anything from her.” But in December 2014, the models were recognized by the cultural worker’s union, which elected two models as delegates, one of whom was Bellaiche. “We outlined 10 articles in a document that stated the acceptable conditions under which a model ought to pose,” he said proudly. “All that started happening in 2014. That was when the wall fell.”

A banner hung by the Collectif des Modèles d’Art de Paris in the Place de l’Hôtel de Ville