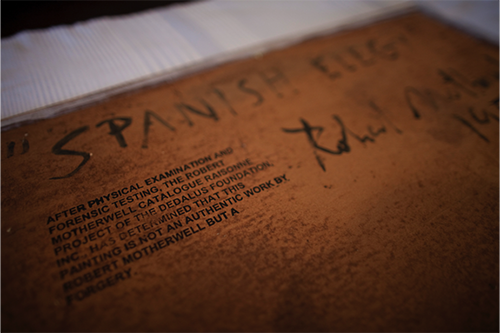

The stamped verso of a forged Robert Motherwell. Image courtesy of the Dedalus Foundation.

Five years ago, the handshake deal in art transactions seemed doomed when two massive forgery scandals sent shivers through the art world. Everyone the market counted on had been fooled. Christie’s and Sotheby’s had sold the forgeries, experts had authenticated them, the Met and other museums had exhibited them, major dealers had circulated them.

In 2010, Wolfgang Beltracchi was arrested in Germany and admitted to forging 20th-century masters like Max Ernst and Fernand Léger. The forgeries may number in the hundreds.

A year later, the prestigious gallery Knoedler & Company, one of New York’s oldest, shuttered amid allegations it had sold some $60 million of fake Abstract Expressionist paintings. The allegations later proved correct. This month, Manhattan federal court Judge Paul Gardephe ruled Knoedler and its former director Ann Freedman must go to trial in two lawsuits brought by angry buyers, New York collector John Howard and Sotheby’s chair Domenico de Sole and his wife, Eleanore. Knoedler and Freedman deny wrongdoing and say they were duped as well. Freedman’s lawyer Luke Nikas told The Art Newspaper that at trial she will “tell her story and prove her good faith.”

“Reaction at the time was raw terror—nothing hits the art world like the ability of an asset to go 100% up in smoke.”

“Reaction at the time was raw terror—nothing hits the art world like the ability of an asset to go 100% up in smoke. […] Systems and structures assumed to be reliable weren’t,” says Jeffrey Taylor, who teaches arts management at State University of New York at Purchase.

How would this new uncertainty be dealt with? Given how easily the forgeries entered the market, it seemed obvious that art world players should no longer be satisfied with the traditional one-line invoice and a gallery’s oral assurances of authenticity.

Five years after Beltracchi’s arrest, it’s time to ask what market participants have learned. Are they checking provenance more carefully, consulting experts, getting written assurances from galleries? What’s changed?

“Nothing,” says art adviser Todd Levin, echoing other art world figures.

Others see what art lawyer Peter Stern calls “an evolution.” “More sophisticated buyers are more cautious,” he says. “Advisers do for them whatever they can to verify authenticity. […] There’s more in writing, particularly when people have legal and art advisers.”

What’s changed? “Nothing.”

There’s a consensus, though, that the very obstacles to determining authenticity highlighted by Knoedler and Beltracchi are still formidable, because the ways of doing business have changed little, if at all.

Consider provenance. If a work can be traced from the current owner back to the artist, it’s almost a guarantee of authenticity. But the art market is notorious for its lack of transparency. With galleries as middlemen, even the seller’s name often isn’t disclosed to the buyer. The Knoedler collectors handed over millions despite the fact that the fictitious owner was never named. The gallery itself knew him only as Mr. X. (Mr. X was concocted by Long Island dealer Glafira Rosales, who brought the forgeries to Knoedler; in 2013 she pleaded guilty to tax evasion, wire fraud, and money laundering.)

Seller anonymity will likely remain one of the rules of the game. “I don’t see things changing regarding willingness of participants to identify themselves, so due diligence can be difficult,” says Judd Grossman, who represented the first collector to sue Knoedler and Freedman. (Ten lawsuits were filed. Four, including Grossman’s, settled on undisclosed terms.) “Sellers have the right to remain anonymous,” says Achim Moeller of Moeller Fine Art.

Even if there’s documentary evidence of provenance, it too can be convincingly forged. Beltracchi told buyers the fakes were collected by his wife’s grandparents. He took photographs of her posed before an array of his forgeries and dressed in decades-old styles. “It was brilliant,” comments art adviser Liz Klein.

“Sellers have the right to remain anonymous.”

Buyers might consider consulting an authenticator, but they “are more and more cautious,” for fear of being sued, says lawyer Stern. Experts entangled in the Beltracchi and Knoedler scandals have been taken to court in both the U.S. and Europe. And many artist foundations have closed their authentication boards in light of the $7 million in legal fees the Andy Warhol Foundation incurred vindicating itself in an authentication suit.

Where does this leave buyers? “They never know” what experts might think, says Dean Nicyper, an art lawyer who, with the New York City Bar Association, is lobbying for legislation that would make suing authenticators more difficult.

Buyers could get some assurances with the kind of written agreements customary in other commercial transactions. A gallery might disclose the seller’s name if the buyer’s lawyer signed a confidentiality agreement, for example. “Most galleries will fix a problem if they’re asked,” says art adviser Klein.

But that’s not the way the art market generally works. Unlike buying a house, where everyone has a lawyer, Grossman points out, art is “one of a kind and buyers don’t want to lose [...] the deal by getting a lawyer involved.” Klein says some collectors buy from someone they trust and leave it at that because “they’re seduced by the social stuff…. They meet artists and think their lives become more interesting.”

“I overly depended on Knoedler’s reputation [...] That was a mistake, and I learned from it.”

One person who’s changed how he operates is veteran dealer Richard Feigen. He was an intermediary in selling a Knoedler fake. “I overly depended on Knoedler’s reputation [...] so I didn’t examine it with the care I would have with an individual or a gallery with less of a reputation,” he says. “That was a mistake, and I learned from it.” (Feigen refunded the money and sued Knoedler and Freedman; the case settled in August).

A Robert Motherwell forgery. Image courtesy of the Dedalus Foundation.

The collectors in the Knoedler lawsuits said they, too, relied on Knoedler’s reputation. In their court papers, Knoedler and Freedman argue that because the buyers were sophisticated, that reliance wasn’t reasonable. Judge Gardephe said that was a question the jury will have to decide.

Working with a reputable gallery still goes a long way. “If you buy from a reputable dealer, your due diligence is in part buying from that dealer,” says Dedalus Foundation president Jack Flam. Flam was instrumental in exposing the Knoedler forgeries when Dedalus discovered that the gallery sold fake Robert Motherwells. Observers think that trust is justified: “Top galleries always have and will continue to do their homework,” says art lawyer Grossman.

“It’s the art world. Memories are short.”

Forensic analysis confirmed the Knoedler and Beltracchi fakes, and it may be the ultimate safeguard for art sold on the secondary market. “Forensic business is growing,” says Nicholas Eastaugh, director of London-based Art Analysis & Research, who identified the first Beltracchi fake. “It will play a big role in the art world.”

ARIS Title Insurance is spearheading an initiative, announced on October 12, “to help prevent disputes on authenticity,” says ARIS chair Lawrence Shindell. A new technology that will be available in the next 30 to 90 days, he says, will permit living artists to identify their work with a bio-engineered DNA marker that will identify the object to subsequent owners. But authenticating works by artists of the past, like those sold by Knoedler and forged by Beltracchi, will still use the traditional tools of due diligence.

Whatever lessons have been learned, will they last? “It’s the art world,” says lawyer Nicyper. “Memories are short.”

—Laura Gilbert