What’s Happened

The Knoedler & Company forgery scandal—which brought down the once-esteemed gallery in 2011 and spawned numerous protracted lawsuits—came to an abrupt halt Wednesday when collectors Domenico and Eleanore De Sole announced a settlement with Knoedler and its parent company 8-31 Holdings, Inc., the remaining defendants in the case. The De Soles had settled with Ann Freedman, the gallery’s former director, on Sunday. Luke Nikas, an attorney for Freedman, told Artsy in a statement: “Ann is pleased to be able to reach this settlement. She stands behind the work that she sells. From the very beginning of these cases, Ann never wanted to keep a penny of the commissions she made on these works.”

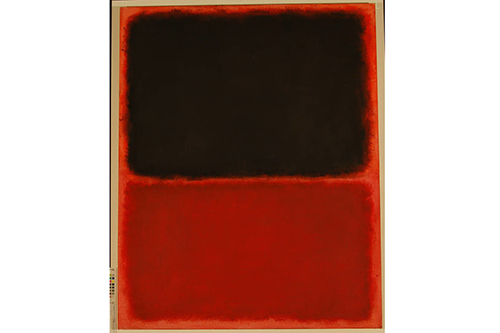

The case against the gallery and holding company was slated to proceed this week, with Freedman and Michael Hammer, Knoedler’s owner, expected to testify on Tuesday. According to ARTNews, just before they took the stand in front of a packed courtroom, the judge dismissed the jury for the day “due to unexpected developments.” Although the trial was set to resume the following morning, it never did. Instead, the De Soles settled with Knoedler and 8-31, effectively resolving the $25 million lawsuit over the family’s purchase of a fake Rothko. Charles Schmerler, Knoedler’s attorney, told ARTNews that Freedman’s earlier settlement had served to “enable a fair, reasonable, and good settlement for the other parties.”

Lawyers would not disclose the terms of either settlement, althoughartnet News reported that the gallery settled a similar lawsuit brought by hedge fund manager Pierre LaGrange for just $6.4 million—despite the fact that he originally purchased his fake Pollock from Knoedler for $17 million. Whether that settlement included an additional sum for the co-owner of the forged work, Canadian investor David Mirvish, is unknown.

The high-profile trial had the potential to determine the crucial (and potentially game-changing) point of law at the heart of the case: Is it the responsibility of the gallery or the purchaser to verify a work’s authenticity? Below, we bring you up to speed in this complicated dispute and discuss what the settlement means for the art world going forward.

The Case

As we’ve previously reported, the prestigious Upper East Side gallery Knoedler & Company shuttered in 2011 amid allegations it had sold some $60 million in forged works falsely attributed to major Abstract Expressionists including Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, and Willem de Kooning. The paintings came to the gallery by way of art dealer Glafira Rosales, who claimed that a secretive Swiss collector had consigned them. Dubbed “Mr. X” by Rosales, the mysterious figure never actually existed. In fact, Rosales commissioned the works from a struggling Chinese artist based in Queens named Pei-Shen Qian (who has since fled to China); she paid him anywhere between a few hundred and a few thousand dollars for each multi-million dollar forgery.

The De Soles’ lawsuit is one of 10 (five of the others have been settled, four remain pending), but it is particularly notable, not least because Domenico De Sole is the chairman of Sotheby’s. The origins of the De Soles’ claim date back to 2004, when the couple purchased what turned out to be a forged Rothko from Knoedler for some $8.3 million. They uncovered the deception in 2011 and filed a lawsuit in 2012, asking for some $25 million in damages, alleging fraud and a litany of related crimes. Interestingly, the De Soles, who highlight what they claim is a coordinated pattern of fraud unfolding over a number of years, are suing under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (“RICO”). RICO allows for a monetary judgement three times the original amount lost and is a statute that is used to prosecute organized criminals.

For their part, the defendants allege that they were duped by Rosales and, regardless, that it is the burden of the De Soles, as savvy and experienced art-world citizens, to verify the authenticity of the work sold to them. In October, the judge presiding over the case ruled that such questions were matters for a jury to decide and the case proceeded to trial.

The Trial

Since testimony began three weeks ago, numerous witnesses have taken to the stand to settle questions about what efforts were made to verify the authenticity of the works and who was aware they were forgeries—and, of equal importance, when. The De Soles argue that upon being presented with a trove of unseen works by major artists at bargain prices, Ms. Freedman should have done more due diligence to verify “Mr. X” and the works themselves. They also state that Freedman knew the works were counterfeit, a claim she strenuously denies, arguing she acted in good faith. Even after Sunday’s settlement, the New York Times reported that Freedman’s lawyer stated his client would “continue to assert that she had believed in the Rosales paintings and would never have sold those works if she had known that they were not genuine.” Freedman even purchased a few forgeries herself.

A Brief History of Art Forgery—from Michelangelo to Knoedler & Company

Earlier testimony included a librarian and archivist hired by Knoedler to look into the identity of “Mr. X,” which she could never verify—although a connection to a major deceased collector was allegedly disseminated as fact by the gallery. Testimony from James Martin, a forensic conservator, noted that the naked eye could tell some of the works were of dubious authenticity and, according to The Art Newspaper, that “Knoedler wanted [Martin] to change the conclusions in his report on two works meant to be by Robert Motherwell.” The president of the Dedalus Foundation also took to the stand, noting that his organization had looked at four works attributed to Motherwell in 2007 and deemed them likely to be forgeries. Others reportedly expressed doubts to Knoedler as early as 1994.

Rothko expert David Anfam took the stand, noting that while he never authenticated the works, he had once written an encouraging email to a Buffalo institution that was thinking about acquiring what turned out to be a forged Barnett Newman. On cross-examination by the defense, he admitted mistaking fake Rothkos for the real thing. Conservator Dana Cranmer also reportedly testified that the De Soles’ Rothko did not look like a forgery upon examination.

Another issue is the scale of the fraud. That is, did Knoedler need to sell forged works in order to keep the gallery afloat? According to the New York Times, testimony last week “indicated” that Freedman personally raked in $10 million in commissions on fake work. The sales, which totaled $70 million, brought the gallery back into the black to the tune of $32.7 million. Knoedler’s lawyer argued that the gallery didn’t need to sell forgeries but could have sold other works to make that money. It’s difficult to know exactly why De Sole and Freedman settled, but Art Market Monitor states that “the prospect of testifying as a witness for the plaintiffs seems to have encouraged” her to settle.

The Takeaway

Forgery cases come and go, but as Laura Gilbert noted last December, this case raised an important question: “Do wealthy collectors with art advisors have a duty to investigate authenticity and research provenance, or can they do what they’ve always done and rely on what a reputable gallery tells them?” The stakes were high. If the jury had sided with the De Soles, the status quo would have endured and the burden would have remained on the gallery. If they sided with Knoedler and 8-31, collectors may have been “burdened with new obligations to investigate authenticity, overturning long-standing industry practice.” Although the resolution of the Knoedler trial leaves these questions unanswered, several additional lawsuits centered around the forgeries have yet to go to court—each with the potential to set a precedent in the world of art law.

—Isaac Kaplan and Abigail Cain

(Lawyers for Knoedler and the De Soles did not respond to Artsy’s request for comment.)