Alberto Burri on Rauschenberg, Fontana and how an artist should manage his market

In a rare interview, the Italian artist spoke frankly about keeping the prices high for his work, saying:

“I can always be a doctor instead”

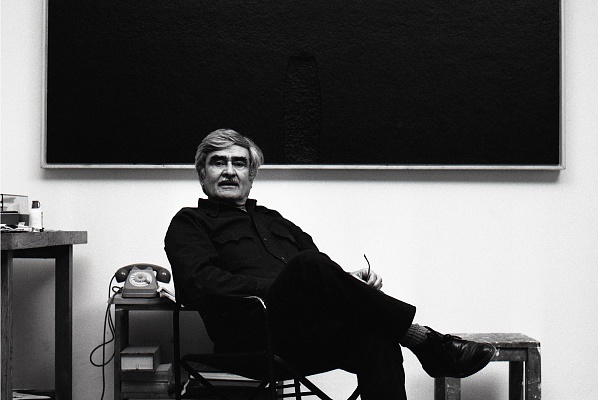

Alberto Burri in his studio in Case Nove di Morra, Città di Castello, Italy, 1982. Photo: Aurelio Amendola

© Aurelio Amendola, Pistoia, Italy

As the first Alberto Burri retrospective in the United States in more than 35 years opens at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, and his work is due to take centre stage at London’s Modern art auctions next week, we reprint an excerpt from one of the most in-depth interviews ever granted by the artist, which was recorded by his friend, Stefano Zorzi. The piece comes from the book Parola di Burri (Burri's Word), published by Allemandi in 1995, the year the artist died.

Stefano Zorzi: We know that after visiting your studio in 1953, Rauschenberg began producing his first “Combine Paintings”. Let’s talk a bit about that meeting and about the artist.

Alberto Burri: First of all, it must be said that right from the outset I did not have a positive impression of the American art world. The year before Rauschenberg’s visit, an American dealer came to see me: Allan Frumkin, who had a gallery in Chicago… He came to visit my studio and told me: “I’d like to do an exhibition about you in Chicago”. This was at the end of 1951 or the beginning of 1952, and my exhibition was to be held within a year.

Frumkin wrote to me often from America, saying that he would send me a cheque to show me what he had sold, but the cheque never arrived… Anyway, when I made my first trip to America since the war in 1955, for “The new decade” exhibition at MoMA, I took the opportunity to go to Chicago to see Frumkin and ask what had happened to my money and my pictures… When I asked for what was owed me, Frumkin told me that he had given all the proceeds of the paintings he had sold to Eleanor Ward of the Stable Gallery [in Manhattan]. So I had to go back to New York after making this futile trip.

That’s how I realised that the attitude of American dealers of the time was certainly no better than that of their Italian counterparts… It was after these experiences that I began my association with the Milanese gallery owner, Peppino Palazzoli, in 1954-55. Palazzoli has been my only dealer, the only one to whom I entrusted my pictures for him to sell and show—in other words, to do everything necessary—and all without a contract, always on trust. He was a friend of mine…

But back to Rauschenberg…

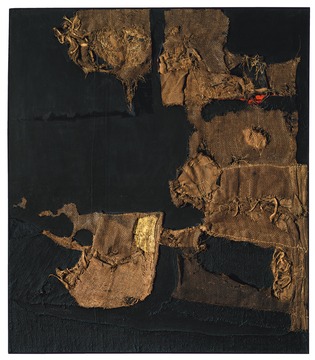

Rauschenberg came to visit me in the studio in 1953. At the time, in my studio, among other things, I had three big Sacchi [burlap sack works] measuring two and a half metres: one that is now in the Fondazione at Palazzo Albizzini, another in the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna and the one that was later bought by the singer Domenico Modugno.

Alberto Burri, Sacco e oro (Sack and Gold), 1953, burlap, thread, acrylic, gold leaf, and PVA on black fabric. Photo: Private collection, courtesy Galleria dello Scudo, Verona, © Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini, Collezione Burri, Città di Castello/2015 Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

Rauschenberg came twice, on two consecutive days, stayed a long time looking and left me as a gift a little box containing some sand and a dead fly... That’s the stuff he was doing then! He had an exhibition at Del Corso with these little boxes “à la Cornell”, so to speak.

And what did you say to each other that time; what did you talk about?

Nothing. We did not open our mouths for the simple reason that at the time I did not speak a word of English and he, naturally, did not know any Italian…

So that’s all there is to your famous encounter with Rauschenberg?

That’s right.

So how do you explain this parallel that critics have always mentioned between you?

Simply because he clearly based himself on my work... I remember a meeting with Dorazio the painter in central Rome in 1954-1955. He said: “I saw an exhibition of Rauschenberg that I initially mistook for a show by you in New York!”

Rauschenberg has of course never accepted any reference to my work even though critics have mentioned the similarities. Unfortunately, no-one has ever written with the necessary clarity that these similarities were caused by the fact that he had been here and seen what I was doing... Because our art critics are cowards, they have a guilty conscience because they are not well-informed.

Sure, it’s all over the place! All that stuck-on paper, or a stick placed just so with a hook and some bird, a dangling eagle... But what does it mean? For me it is just a bit of American showiness.

One of your first buyers was Lucio Fontana, who bought Studio per lo strappo at the Venice Biennale in 1952. Why him, rather than Italian collectors like Emilio Jesi or Riccardo Jucker?

The painter always has a different sensibility to that of a collector when choosing the picture of another painter. These were collectors who were not yet sufficiently prepared for my things… They liked figurative art and would buy anything that had a recognisable form—they bought de Chirico’s horses, they certainly did not want my sacks. The great collectors of the time, Jucker, Jesi and so on, were all wealthy industrialists but traditionalist too.

Fontana has also stated publicly, to a critic in Verona, that in my tears he found the origin of his own slashes...

Many say that have been the most successful artist to manage his market.

The point is that I painted when I wanted to paint, when I felt like it, and I only sold at the prices I established.

So you kept prices high.

Sure, right from the first picture I sold! In 1947, the price for a small painting by me was already 15,000 lire [around $164,000, including inflation]. The price could not be lower, or I would have said, “hold on, stop everything: what do you want from me? Because I can always be a doctor instead!” Do you believe that there is difference between a doctor and a painter from my point of view? No there isn’t!

And have you always managed to keep your market at that level?

And how! Otherwise I wouldn’t sell.

So the secret was not to sell...

Don’t sell, and then raise the price when necessary... only if you’re hungry do you absolutely have to sell.

In this way you have always only partly satisfied market demand and this has allowed you to keep prices high. So that’s all there is to the secret of the “Burri management”: few pictures and sustained prices.

Yes, what other secrets could there be... For a lot of people, there’s still a whiff of sulphur about me, I’m seen as “evil”... But in reality, I was only fulfilling what I considered to be the right demand for my pictures, and no one has ever been “damned” for buying them. The market has always gone up because the pictures were worth it, otherwise they would not have risen.

But how do you feel about the record of about three billion lire paid at an auction in France for one of your works?

I thought: “You see, at last there is someone who recognises something...”

With all the money that your pictures are worth, you should be extremely rich. If you are as good at managing yourself as you say...

I don’t want to be rich. I wouldn’t know what to do with the money; I can live quite happily as things are. I have always had pretty much everything I wanted: I have been able to go to America, I have travelled, I have had large and luminous studios. I’m extremely satisfied with all I have had.