Iraqi food truck installation hits Chicago’s streets

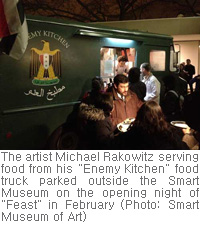

Iraqi food truck installation hits Chicago’s streetsThis weekend, Enemy Kitchen, an ongoing project by the artist Michael Rakowitz, hit the streets of Chicago. The work, a food truck serving regional Iraqi cuisine, staffed by American veterans of the Iraq War and Iraqi refugees, was mobilsed just in time to mark the ninth anniversary of the start of the war.

The project started in 2004 as an after-school programme, where students created dishes using recipes borrowed from the artist’s Iraqi-Jewish mother. Rakowitz is known for his practice of social engagement and his continuing examination of the Iraq war includes an ongoing series of reconstructed archeological artefacts that were looted from the National Museum of Iraq.

Enemy Kitchen first came to Chicago last month for the opening of “Feast: Radical Hospitality in Contemporary Art” at the Smart Museum (until 10 June). Meals were served on paper plate reproductions of china looted from Saddam Hussein's palaces; Rakowitz had previously used the real china for a project with the New York public art producers Creative Time, but the plates were returned to Iraq at the end of last year after a request from the Iraqi embassy, just as the US started pulling troops out of the country.

Every detail of the truck has been considered—from the font used on the signs to the colour of the vehicle. The flag that flies from the truck is the Chicago flag in Iraq’s colours. “It looks uncanny, exactly like the Iraqi flag,” says Rakowitz. Bolted to the side of the truck is a soap dispenser filled with rose water, its metal case engraved with the words Ysallim idak, meaning “May God bless your hands”. It is often common to say that to a chef after a delicious meal. With that, Rakowitz conflated two ideas: “Often, after a meal the host drips rose water on the guest’s head, so you leave with this aroma.” Rakowitz likens it to a Proustian experience of smell and memory.

During its tour of Chicago, Rakowitz will park the truck near obvious art institutions, but he also plans to visit neighbourhoods where there is heavy military recruiting. “Not with any particular agenda, but because that could be a site for potentially interesting conversations,” says Stephanie Smith, the curator of the Smart Museum show. Visitors can also find the location of the truck on Twitter, under the profile @EnemyKitchen.

At the end of the exhibition in June, Rakowitz says he is turning the truck over to the owners of a small restaurant, Milo’s Pita Place, which has lent the artist the use of its kitchen. In this way, the project will live on as a place for conversation and as a microeconomy for veterans and refugees. “[Enemy Kitchen] is not limited by the closing date of the museum,” Rakowitz says.

Iraqi food truck installation hits Chicago’s streets

Iraqi food truck installation hits Chicago’s streets