Young British Artists 2.0 try to make way in wake of Hirst and co

Young British Artists 2.0 try to make way in wake of Hirst and coThe YBA days of pickled sharks and stardom are long gone, but as a new art guide shows, there is top talent for a soberer time

As Damien Hirst dusts off his £50m diamond skull in preparation for his Tate Modern retrospective this spring, a new generation of young British artists are working in a very different climate from the brash super-confidence of his 1990s heyday.

"Before I did an art degree I knew I wasn't doing it for financial gain," says Max Dovey, 24, who graduated with a first in fine art from Wimbledon Art College last year.

"At art school I was always telling everyone else that no one would be a successful artist, to make sure they had a skillset so they'd be employable and [not to] wait to be picked by [Charles] Saatchi because it won't happen."

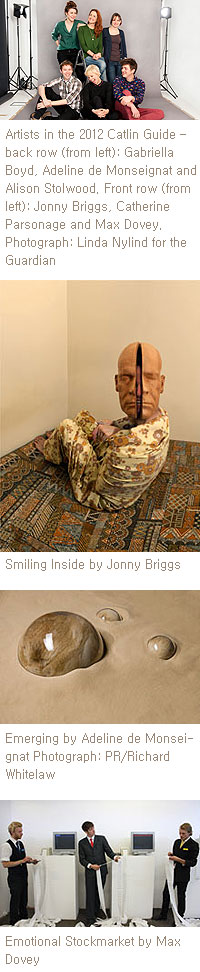

Yet there are flecks of light for Britain's fledgling painters, sculptors performance artists and video installation-makers – not least from the Catlin Guide 2012, being launched at the London Art Fair on Wednesday.

The guide showcases what its editor, Justin Hammond, claims are the country's 40 most promising young artists.

Some art world observers say the guide is premature, as it is based on BA and MA graduate shows. But many of those chosen – from recommendations by tutors, bloggers, collectors and critics – have received recognition elsewhere.

Alison Stolwood's work was selected for the influential Bloomberg New Contemporaries show at London's ICA. That work, a photographic animation of a wasp's nest spinning back and forth, has been sold and will be exhibited at Preston's Harris Museum later this year.

Meanwhile, Royal College of Art graduate Jonny Briggs has defied Dovey's dire prediction and has sold work to Saatchi, But the days of Hirst and the Young British Artists (YBAs) – when this would have been a fast track to stardom – have long passed.

In October Briggs, 26, won New Sensations, a competition created by the Saatchi Gallery and Channel 4 to find Britain's most talented art graduate.

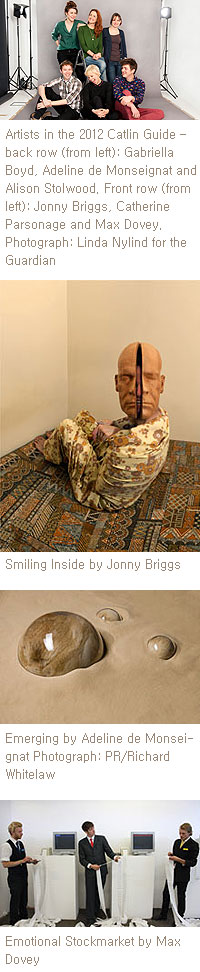

His work documents his attempts to "connect with his childhood self", and includes a photograph of him wearing a giant wooden mask made to look like his father's face.

This theme could be taken as making a virtue out of necessity; Briggs cannot afford to move out of his parents' home, though he does rent a studio in a former factory in south London "where Twiglets were invented".

Of the other artists picked by the Catlin Guide, Gabriella Boyd, a graduate of the Glasgow School of Art who was runnerup in the competition, has managed to fund her large-scale oil paintings through portraiture commissions.

Adeline de Monseignat, who makes disconcerting sculptures she accurately calls "hairy eyeballs", works as a nanny to pay the rent on her studio. But she has recently sold two works.

Catherine Parsonage, 22, considers herself "incredibly lucky" to have won a scholarship from the RCA, though, she says, she is "struggling – it's expensive to live in London".

Her portrait of her friend Charlotte was longlisted for the BP Portrait award at the National Gallery last year.

Few young artists are producing work with the in-your-face iconoclasm of classic YBA works such as Hirst's shark in formaldehyde or Tracey Emin's My Bed.

Dovey is a performance artist. Previous work includes The Emotional Stock Market, which recreated an exchange based on the "trading" emotions every time they were mentioned on Twitter.

He says that the bold individualism of the YBA years, when art schools encouraged students to create their own brand identity to make them stand out in the art market, has given way to more diverse, less easily digested work, as well as a more sober attitude. "The YBAs made art school a very cool place to be, and possibly a very golden route to stardom," he says.

"Slowly there are becoming more and more realists around the art school environment. "With the rise in fees, I hope prospective students looking at creative courses in art school will value coming out with an employable skills-set over a strong professional art identity.

"So the effect of the YBAs on academia is slowly wearing off, which – looking at the economics and the politics – is probably a really good thing."

Most of the artists say the tough financial climate has led to a greater atmosphere of collaboration and mutual support.

Stolwood says that her peer group from Brighton University "email if there are any competitions people should apply for", while Boyd's colleagues band together to try to stage exhibitions.

Though this year's students have to contend with increased fees, the British art market is still buoyant, outperforming the stock market by 9% last year.

De Monseignat says that while she will go and see Hirst's retrospective, the YBAs are now part of art history.

"At some point every artist has to be interested in them and understand what happened at that point in the UK," she says. "It's a very important period."

And despite Hirst's continuing presence, one that seems a long way in the past.

guardian.co.uk,

Tuesday 17 January

2012 15.01 GMT Article history

Young British Artists 2.0 try to make way in wake of Hirst and co

Young British Artists 2.0 try to make way in wake of Hirst and co