Papa’s Damn Good Pictures

Papa’s Damn Good PicturesERNEST HEMINGWAY the hunter, Hemingway the fisherman, Hemingway the drinker — they’re all part of the legend. Among the motifs in “The Select,” the Elevator Repair Service staging of “The Sun Also Rises,” currently at the New York Theater Workshop, is an inside joke about how much imbibing takes place in that book.

But Hemingway the art lover? If you haven’t read “A Moveable Feast” or seen “Midnight in Paris,” the recent Woody Allen film that takes place partly in 1920s Paris, you might not know that through Gertrude Stein, Hemingway became friendly with many of the painters there. He even had a small personal collection, including etchings by Goya and paintings by Gris, Miró and Klee — artists who in some ways mirrored his own modernist aesthetic.

And he was a museumgoer of sorts. When in New York he was as likely to visit the Metropolitan Museum as Toots Shor’s.

In general Hemingway had little use for New York, which he called a “phony town,” and it tended to bring out the worst in him. On his most famous visit to the city, the one chronicled in Lillian Ross’s scathingly brilliant profile in The New Yorker in 1950, he mostly behaved like a parody of himself, more exaggerated even than the Hemingway character in “Midnight in Paris,” who is always looking for a fight. In the profile Hemingway swills a lot of Champagne, some of it in the company of Marlene Dietrich — the Kraut, he calls her — and never tires of wheezy old boxing metaphors: “I started out very quiet and I beat Mr. Turgenev. Then I trained hard and I beat Mr. de Maupassant. I’ve fought two draws with Mr. Stendhal.”

Even worse, Hemingway also lapses frequently into baby talk, or maybe it’s mock American Indian. “Not trying for no-hit game in book,” he says of “Across the River and Into the Trees.” “Going to win maybe 12 to nothing or maybe 12 to 11.”

Aside from buying a coat and a pair of slippers at Abercrombie & Fitch, Hemingway didn’t accomplish much on that visit. But with his wife, Mary, and his son Patrick, known as Mousie, a sophomore at Harvard, he did drop by the Met and spent a couple of hours looking at paintings, periodically topping himself up from a little pocket flask.

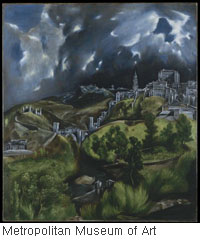

The paintings Hemingway lingered over, according to Ms. Ross, are an extremely odd and eclectic bunch: Titian’s “Portrait of a Man,” Francesco Francia’s “Portrait of Federigo Gonzaga,” van Dyck’s “Portrait of the Artist,” Rubens’s “Triumph of Christ Over Sin and Death,” El Greco’s “View of Toledo,” Reynolds’s portrait of George Coussmaker, Cabanel’s portrait of Catharine Lorillard Wolfe, Cézanne’s “Rocks — Forest of Fontainebleau,” Manet’s portrait of Mlle. Valtesse de la Bigne, and Carpaccio’s “Meditation on the Passion.” (He also wanted to look at Bruegel’s great painting “The Harvesters,” but its gallery was closed that day.)

The Met has since sold the Rubens, and the Cézanne is not currently on view, but the other pictures are still there, and a contemporary museumgoer can spend a baffling hour or so trying to discern what, if anything, links them to what we know of Hemingway’s life and work.

The Reynolds portrait, depicting a lordly and swaggering army officer, makes a certain amount of sense. Hemingway called it “a damn good picture,” and said approvingly, “Now, this Colonel is a son of a bitch.” He added, “Look at the man’s arrogance and the strength in the neck of the horse and the way the man’s legs hang.”

But at least two of the other portraits seem positively sissyish. The van Dyck self-portrait, though a great painting, is of a foppish, effeminate figure, with rouge-red lips and long tapered fingers adorned with a little pinkie ring. Not exactly Hem’s type, you would have thought, especially considering that at the other end of the gallery these days is a giant and gory hunting scene from Rubens’s workshop with hounds and horses and a guy stabbing a wolf with a spear.

Federigo Gonzaga was about 10 when Francia painted him, and in the picture he has a dreamy, eye-rolling expression. Far from suggesting grace under pressure, that greatest of Hemingway virtues, it makes you think that he’s about to pass out. What on earth did Hemingway see here? The trees in the background. “This is what we try to do when we write,” he said pointing them out to his son. “We always have this in when we write.”

Hemingway’s choice of female portraits is similarly mystifying. The Cabanel painting of Catharine Lorillard Wolfe is far from a great picture and is remarkable mostly for its subject. She was a great tobacco heiress and an early benefactor of the Met’s, and she looms here stiff and formidable, decked out in fur-trimmed lace. What Hemingway said he liked about the Manet portrait — a pastel sketch, really — of Valtesse de la Bigne was that it was an example of how “Manet could show the bloom people have when they’re still innocent and before they’ve been disillusioned.” He must have been misled by Mlle. de la Bigne’s high-ruffed collar and yearning, pale-blue eyes. She was actually a famous, high-priced courtesan, most likely the model for Zola’s Nana.

Are there any common traits in the paintings Hemingway picked out? Well, beards maybe. The luxuriant reddish chin warmer, looking like paste-on stage whiskers, is the chief point of interest in the Titian portrait (of another effeminate-seeming young man, come to think of it). And in the Carpaccio Passion painting, St. Jerome and Job, flanking the stricken Jesus, each sprouts a beauty, the kind of beard you need to be a hermit or a desert-island strandee to grow.

And in both the Bruegel and El Greco, if you look very carefully, there are tiny sticklike figures in the background (fishing in El Greco and playing on a village green in Bruegel): a level of detail barely visible but suggesting a Hemingway-like precision and desire to get things right. Hemingway said that what he most liked about “The Harvesters” was the way the artist used the geometry of the grain to “make an emotion for me that is so strong I can hardly take it.” In its plainness and honest depiction of ordinary lives, it’s the painting that most nearly resembles his fiction.

“View of Toledo,” on the other hand, is in some ways a dishonest painting, or a deliberately inaccurate one, depicting the city not as it really looks but as El Greco liked to imagine it, and yet of all the pictures in the Met this was Hemingway’s favorite. It is moody and evocative, rather than precise and finely observed — more nearly Stephen Vincent Benét, say, than Hemingway.

So in the end it’s hard to conclude more about Hemingway’s taste in art than that he knew what he liked, or thought he did, and that except for El Greco and the Carpaccio, a truly eccentric picture, his taste tended toward the conventional, the middlebrow and even the prissy. He was drawn to the kind of paintings that Paul, the pedantic, know-it-all character in “Midnight in Paris”— the Hemingway opposite — would have liked. Go figure.

Papa’s Damn Good Pictures

Papa’s Damn Good Pictures