The Sky Line

Shaping The VoidHow successful is the new World Trade Center?

by Paul Goldberger September 12, 2011

You get a sense of how different things are now from the way they felt the first couple of years after 9/11 when you look back at various master plans that were proposed for rebuilding the World Trade Center site. The runner-up proposal, by a consortium of architects working under Rafael Viñoly, suggested replicating the profile of the original Twin Towers with a pair of steel skeletons. A few cultural institutions would have been inserted into the gargantuan latticework, but the real point of the structure was to evoke the buildings that were no longer there. I remember thinking that the concept looked powerful. Yet if the emotions of that time had led to its being chosen—as it almost was—we would probably now find it bizarre, and disquietingly obsessed with the past. Then, there was Norman Foster’s proposal, a pair of towers with the opposite problem: they reinterpreted the architecture of the World Trade Center with exquisite finesse, but they were all business, and left little room for commemoration.

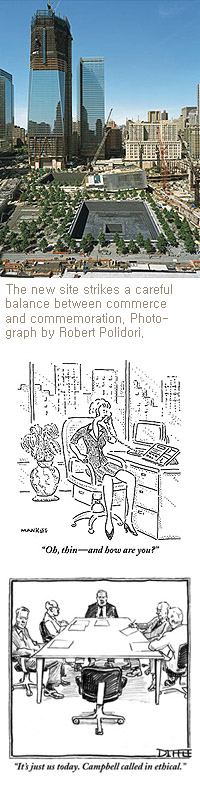

The master plan that was eventually selected, by Daniel Libeskind, split the difference, arranging a number of office towers around a memorial space occupying the footprint of the Twin Towers. This failed to satisfy some relatives of the dead, who wanted the entire sixteen acres preserved as a memorial, and also people who thought that the Twin Towers should be replaced with a new business district as quickly as possible. But Libeskind saw how wrong both these attitudes were. Declaring a permanent void in the heart of lower Manhattan would only have crippled the city’s recovery—hardly the best way to honor people who died as they went about their work. And it would have been unthinkable to rebuild Ground Zero as a purely commercial site, as if nothing at all had happened there. Libeskind’s plan struck a careful balance between commemorating the lives lost and reëstablishing the life of the site itself.

The plan has been followed, more or less, as construction has stumbled forward over the past decade, but, after winning the competition for the master plan, Libeskind never managed to get a commission to design even a single building himself. His rough ideas for the layout were accepted, and then politics and horse-trading took over. Ten years on, the long-term shape of Ground Zero is coming into focus. It is turning out to be one part Daniel Libeskind to several parts Larry Silverstein, the real-estate developer who held the lease on the World Trade Center. Silverstein asked various architects to build skyscrapers on the site, none of whom, at least so far, have produced anything close to their best work.

It says something about the interminable wrangles over Ground Zero that, of the towers planned for the site, only two are currently far enough along to be visible aboveground: 1 World Trade Center, once known as the Freedom Tower, by David Childs, of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, and 4 World Trade Center, by Fumihiko Maki. Even these are a couple of years away from completion. Others—2 World Trade Center, by Norman Foster; 3 World Trade Center, by Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners—have yet to reach street level, and it’s not clear when they will get built.

Some of the early versions of 1 World Trade Center showed promise. There was one with wind turbines; others had sky gardens. But the design has been whittled away, until it has become not much more than a big version of a typical New York developer’s skyscraper. It will be the tallest building in New York, and it still has the subtle taper and the elegant octagonal ascent that David Childs gave it. But the reflective glass skin is the sort of thing you see everywhere. It’s unclear how the Port Authority and the developer Douglas Durst, who took over the building from Larry Silverstein, will decide to cover up the fifteen stories of concrete that security officials have insisted are necessary to protect the building’s base. Childs had planned for an ingenious coating of prismatic glass, which would animate the base on the exterior, but it was recently jettisoned, on practical grounds, and no one is talking about what will take its place. Given that this tower’s base has to be as solid as a bunker, it seems oddthat Maki’s 4 World Trade Center, close by, is permitted to have a bright, welcoming four-story lobby made of glass.

Only a few feet away from the memorial space of the Twin Towers’ footprint is a trapezoidal entry pavilion, designed by the Norwegian firm Snøhetta, for an underground museum designed by Aedas. The pavilion, which will not open until next year, is a kind of tilted box; it’s covered with a striped metal sheathing, and one end is largely of glass. The shape is a little discordant; from some angles, the building looks like a metallic whale beached beside the memorial. I didn’t realize from the original plans how intrusive a building would seem right there. It will be better, I suspect, from the inside. The glass end, an atrium that bears a resemblance to Libeskind’s work, will house enormous steel pieces salvaged from the base of the façade of the World Trade Center; the result may well feel like an uneasy marriage of historical artifact and monumental sculpture.

A performing-arts center, designed by Frank Gehry, is planned for just east of 1 World Trade Center, but there isn’t a final design yet, because planning can’t begin until a new transport hub is finished and more money is raised. The site is far from ideal, since it is over the PATH train tracks, which means that the arts center will cost much more to build than it would elsewhere. The Port Authority controls another site, just south of Ground Zero, where the Deutsche Bank Building damaged on September 11th once stood, and which is designated for another office tower. It would make more sense to build the arts center there, and to hold the site beside 1 World Trade Center for the office building, which couldn’t begin until the market improves anyway.

It’s far too early to know how good the new transport hub, designed by Santiago Calatrava, will be, and whether the extraordinary amount of money it has cost—more than two billion dollars, at last count—will be worth it. Calatrava has a way of creating swooping, curving forms that many people find exhilarating, and which at their best are convincing attempts to convey a new kind of civic monumentality. Other times, as at the Bilbao Airport, they can look like warmed-over versions of Eero Saarinen’s great T.W.A. terminal, at J.F.K. But there’s a hope that Calatrava’s design may be the most successful work of architecture at the World Trade Center. Right now, that title would have to go to a building that isn’t even on the main site: 7 World Trade Center. Across the street from Ground Zero, it was designed by David Childs and finished five years ago. It’s more refined than the big tower, and it reminds you how many good things have happened outside the sixteen acres of the main site since 2001. After September 11th, it looked as if the future of lower Manhattan would depend entirely on what we managed to do with Ground Zero. But the past ten years have proved the opposite. Lower Manhattan healed more quickly around its gaping wound than anyone would have thought possible, with a flourishing of housing, restaurants, cultural facilities, and parks. While politicians, developers, bankers, architects, and almost everyone else quarrelled over the future of Ground Zero, the rest of lower Manhattan, as well as most of the rest of the city, quietly pulled itself together.

This month, a small portion of Ground Zero will open to the public, to mark the tenth anniversary of the terrorist attacks. Because so much of the site is unfinished, the main thing on view will be the memorial to the victims of the attacks, built on and around the footprint of the two World Trade Center towers. This is chiefly the design of Michael Arad, a young architect whose entry was chosen, in 2004, from among fifty-two hundred entries, the largest such contest in history. Early on, public officials made the sensible decision that, whatever happened at the site, nothing new would rise exactly where the Twin Towers had stood. Arad didn’t tiptoe around the footprint; instead, he made it the basis for a strong, almost minimalist design, turning the footprint of each tower into a square hole, with waterfalls running down the sides into a reflecting pool below. At the center of each reflecting pool is another, smaller square, into which water tumbles, as if it were flowing to the center of the earth. Arad figured out how to express the idea that what were once the largest solids in Manhattan are now a void, and he made the shape of this void into something monumental. The names of those who died are inscribed in inch-and-a-half-high letters cut into bronze panels that surround both pools. The lettering will appear dark during the day, and by night will glow, with lighting hidden below the panels.

Early in the design process, Arad was teamed with the landscape architect Peter Walker, who shares his minimalist sensibility, and they have made the space around the two footprints a handsome and restrained civic square, with oak trees, benches, and light poles giving the place a kind of quiet, firm order. You wouldn’t mistake it for an ordinary park or urban piazza, but it isn’t a cemetery, either. You feel a sense of dignity and repose, and you see the shapes of the renewed city in the rising skyscrapers, as you should. Ground Zero can’t be a place where your thoughts escape completely into history, as at Maya Lin’s extraordinary Vietnam Veterans Memorial, or on the battlefield at Gettysburg. You are in the middle of the city, part of an urban life that was as much a target of the terrorists in 2001 as the lives of three thousand people. The people will not come back, but the life of the city has to. When you stand in Arad and Walker’s park and look toward the footprints ringed by names and the new towers behind them, you feel the profound connection between these two truths.

The Sky Line

The Sky Line