Black Holes

Black HolesThere is nothing comforting about the 9/11 memorial.

By Witold Rybczynski

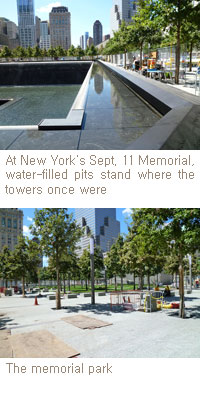

Architect Michael Arad and landscape architect Peter Walker are credited with the design of the 9/11 memorial in New York City, which will be opened to the public on Sept. 12, but an unintentional third designer is Rudolph Giuliani, who as mayor supported the idea that the World Trade Center site was "hallowed ground" on which nothing should be built. By 2003, when a competition was held for the design of the memorial, the idea that the one-acre footprints of the twin towers should be preserved had hardened into a requirement. And that is what people will see on Sept. 12: two vast water-filled pits where the towers once stood.

The design of what has turned into a $700 million memorial has been much simplified since the competition, which is all to the good. The underground museum remains, but no longer theatrically looks out through a veil of falling water. The names of the deceased, originally below ground, have been moved to the surface. The pits, 192 feet by 192 feet and 30 feet deep, are lined in black granite—black as death. Water cascades down the four walls and disappears into a square hole in the center of the pool. The effect is quite beautiful—and the sound of the cataracts effectively masks the noise of the surrounding city. But more than beauty is required of a memorial; one searches for meaning.

It is hard not to think of another abstract memorial designed by an unknown competition winner: the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Maya Lin's design has been characterized as a gloomy tombstone; nevertheless, the act of ascending, after having descended into a kind of underworld, has an oddly comforting effect, and the names, arranged chronologically, have a severe poetry. But there is nothing comforting about gazing into the vast pit—or, rather, two pits—of the 9/11 memorial, the water endlessly falling and disappearing into a bottomless black hole. The strongest sense I came away with was of hopelessness.

The 2,983 names on the memorial include not only the victims of the attack on the World Trade Center but also those who died at the Pentagon and Shanksville, Pa., as well as the six victims of the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center. First responders are not identified, which seems wrong. The much publicized wrangling about how the names should be listed has produced a largely random arrangement, despite the architect's effort to produce what he calls "meaningful adjacencies." But meaningful to whom? A national memorial should speak to more than the families of the victims.

The names are incised in a bronze parapet that rings each pit. The boxy parapet looks simple but is actually complicated: It is cooled inside in the summer, to make sure that the dark bronze surface with the names does not get too hot to the touch, and heated in the winter to prevent ice from forming. In addition, lights illuminate the names from within. This may not strike you as excessive—it does me—but it is a reminder that nothing at the memorial is exactly what it seems. The water that appears to drain into the hole is pushed along by peripheral water jets beneath the surface of the pool. The hallowed ground of the memorial park is actually a concrete slab suspended above a museum, train tracks, and other urban infrastructure. The space immediately below the walking surface houses tunnels that provide access for maintaining the roots of the swamp white oaks (400 of them, eventually) that grow in planting trenches, boxed urban trees being notoriously difficult to cultivate.

Although next week's 10th anniversary is billed as the opening of the memorial, the truth is that it will be years before the World Trade Center site is complete. Since the two water features are part of an eight-acre park, until that is finished, it is too early to make a final judgment on the memorial. The park will be approached at street level from any of the surrounding four streets, and this intimate connection to the life of the city—at the moment the memorial is isolated from its surroundings—will hopefully counteract the nihilism of the black pits. An eight-acre park in the center of Lower Manhattan is bound to attract people. The proximity of grieving families and lunching office workers will be unusual, but New Yorkers undoubtedly will find ways to make it work.

Black Holes

Black Holes