Art Collector Henry Bloch Keeps His 'Pretty Pictures' On His Own Terms

Henry W. Bloch and his wife Marion lived for years with a collection of Impressionist and post-Impressionist paintings. Bloch recently donated them to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art and replaced the works

in his home with replicas.

For two decades, Henry W. Bloch, co-founder of H&R Block, and his wife Marion, collected what they described as "pretty pictures" — mostly French Impressionist works by the likes of Degas, Matisse, and Monet. Nearly 30 of these paintings filled the walls of their Mission Hills, Kansas home.

Although these masterworks are not there now — you wouldn't know it by looking.

The Blochs started collecting art in the 1970s for a very practical reason. "My wife and I had a home and we needed pictures in it," he recalls.

The first Impressionist painting Marion and Henry Bloch purchased was this oil study by Renoir,

'Woman Leaning On Her Elbows.'

In the early years, there were a few missteps, like a Dutch painting that turned out to be a fake. But, taking the advice of Ralph T. Coe, former director of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, they hit their stride, starting with a small oil study by Renoir of a woman leaning on her elbows.

"I liked it, it’s just a little tiny picture," says Bloch. "So I bought that, then we decided to collect Impressionist pictures."

From 1975 to 1995, the Blochs amassed a collection, through auctions and dealers. And they lived with the works — in the dining room, living room, hallways, and bedroom.

There’s a Manet painting, The Croquet Party, of friends and family playing croquet; and a Degas pastel, Dancer Making Points, of a dancer in a yellow dress. There are also paintings by van Gogh, Monet, Matisse, and Gauguin, among others.

Henry served as a longtime trustee at the Nelson-Atkins, and in 2010, the Blochs promised their paintings to the museum after their deaths. But, after Marion died in 2013, Henry decided to hand over the collection a little early.

But that created a problem — walls, that would be empty without the pictures.

"They've built a world that’s very intimate and personal in their homes and to come in and kind of disrupt it late in life could be kind of challenging," says Steve Waterman, director of presentation at the Nelson-Atkins.

One idea was to use photographs of the Bloch collection taken before an exhibition that opened the Bloch Building, named for Henry and Marion, in 2007. Waterman says creating a replica print, that didn't look like a poster at a gift shop, took some trial and error.

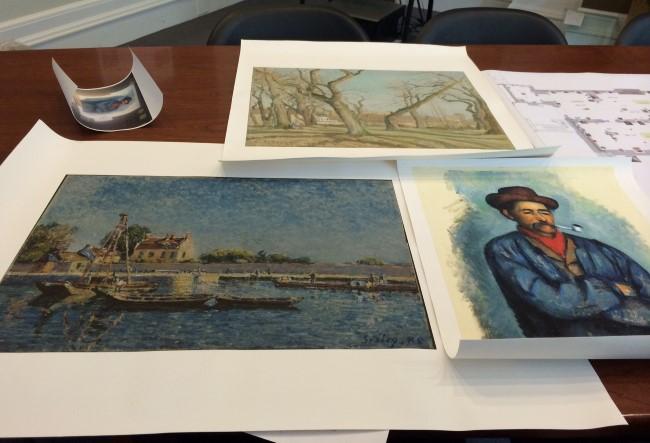

Examples of some of the replica prints, that didn't make the cut, are on display in the design team's work space.

"We just basically went back to that imagery and experimented with printing it on different kinds of paper," Waterman says. "The paper we ended up using has a slight canvas-like texture, so it does a great job of fooling the eye."

Close attention was paid to matching colors and creating a sense of texture. The museum printed the reproductions mostly in-house at a minimal cost.

Waterman says it took a few months — one week at a time — to swap out the originals with the replicas.

"They have a depth to them that’s surprising," he says. "And I remember seeing Henry a few times, reaching out and touching them just to try to confirm that in fact they weren’t the real thing."

Other collectors have done this, too. When publisher Walter Annenberg, and his wife, Lee, donated their collection of Impressionist and post-Impressionist drawings, watercolors, and paintings to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, reproductions were also created for their home.

"It is a perfectly natural thing to do," says Philippe de Montebello, former director of the Met, "and accompanies what is a grand public gesture of generosity."

The Bloch collection provides something, he says, that the Nelson-Atkins didn't have before: critical mass.

"It transforms a good collection into a major representative panorama of French Impressionists, and post-Impressionists with wonderful works by major artists, Manet, Seurat, so many others," de Montebello says. "The great names are there."

These great names are now in the collection of the Nelson-Atkins. And the replicas are carefully hung, in their original decorative frames, on the walls in Henry Bloch's home.

"They're just wonderful. They are absolutely identical," Bloch says. "I often say, are you sure you gave me the copies?"

While the museum has the originals — they won't be on view until at least the spring of 2017. A two-year, nearly $12 million renovation, paid for by the Marion and Henry Bloch Family Foundation, is underway —creating more room to display the museum's expanding European collection.