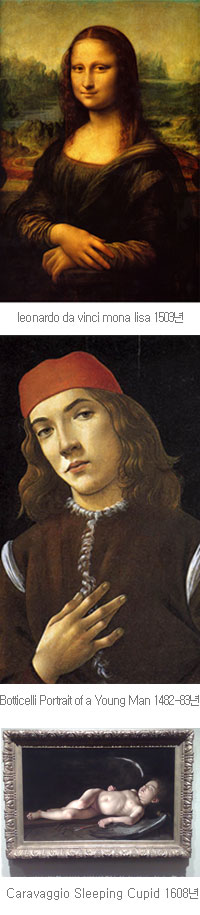

Behind the smile Mona Lisa may have been suffering from high cholesterol

Behind the smile Mona Lisa may have been suffering from high cholesterolIn Leonardo Da Vinci's Mona Lisa there is said to be clear evidence around the left eye socket of xanthelasma, a yellowish collection of fatty acids underneath the skin, suggesting high levels of cholesterol. There also evidence on the hands of subcutaneous lipomas, benign tumors composed of fatty tissue

Richard Owen in Rome

Is she enjoying a private joke? Is she sneaking a sly glance at an unseen lover? Or is the glint in the Mona Lisa’s eye in fact the result of a build-up of fatty acids around her eye socket, a sure sign that she wasn’t watching her cholesterol?

An Italian medical expert says he has found evidence of a range of afflictions in some of the world’s greatest works of art. Vito Franco, Professor of Pathological Anatomy at the University of Palermo, claims that there are clear signs of diseases, from bone malformations to kidney stones, that cast certain icons of perfection in a very different light.

Professor Franco, who presented his findings at a European congress on human pathology in Florence, told The Times that he had begun studying art masterpieces for evidence of disease and illness two years ago.

“I look at art with a different eye from an art expert, much as a mathematician listens to music in a different way from a music critic,” he said. He added that he had analysed about 100 art works, from Egyptian sculpture to contemporary paintings but his focus, he told La Stampa, was on Old Masters. He found that not only aristocrats but also Madonnas, angels and mythical heroes — or at least the sitters — revealed telltale signs of illness.

In Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas (The Maids of Honour), at the Prado in Madrid, the five-year-old Infanta Margarita depicted with her attendants at the court of Philip IV appears to be a victim of Albright syndrome, “a genetic illness involving precocious puberty, low stature, bone disease and hormonal problems”.

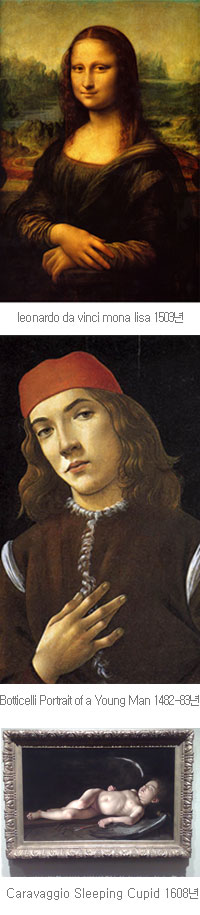

The “almost feminine” elegance of the young nobleman in a red velvet hat and wearing a gold medal in Sandro Botticelli’s Portrait of a Young Man at the National Gallery in Washington was due to his unnaturally long, thin fingers — a sign of arachnodactyly, or “spider fingers”. This condition is linked to Marfan syndrome, a genetic defect apparently visible in Parmigianino’s long-necked Madonna, at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence.

Sufferers from Marfan syndrome, first identified by the French physician Bernard Marfan in 1896, tend to be unusually tall and thin with disproportionately long limbs.

Another famous Virgin Mary, the Madonna del Parto by Piero della Francesca, has a goitre, or swelling of the thyroid gland, on her neck “typical of people who drank water from a well in certain areas” in medieval times. This produced a deficiency of iodine, which caused changes in the thyroid.

Michelangelo’s own ailment, which Professor Franco diagnoses as kidney stones — is shown in Raphael’s School of Athens where he appears with strangely swollen and knobbly knees. Michelangelo complained of kidney and bladder problems in his letters and may have suffered from gout.

Behind the smile Mona Lisa may have been suffering from high cholesterol

Behind the smile Mona Lisa may have been suffering from high cholesterol