정준모

Skinny-dippSkinny-dipping in the void: the day I toured James Turrell's art show nakeding in the void: the day I toured James Turrell's art show naked

A nude tour of the artist’s light sculptures is more than a gimmick, discovers our culture writer, as she joins the naturists and curious art students in Canberra

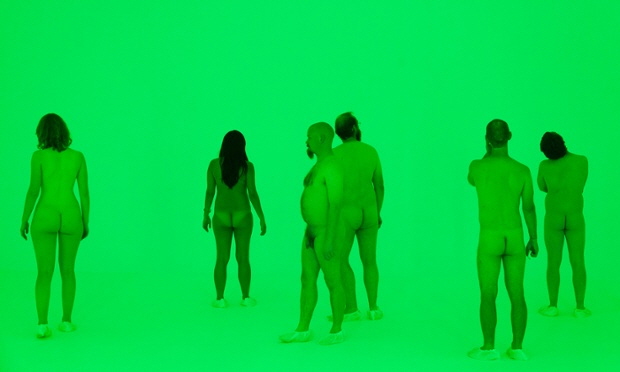

James Turrell’s 2014 work Virtuality Squared and participants of Stuart Ringholt’s piece: Preceded by a tour of the show by artist Stuart Ringholt, 6-8pm. (The artist will be naked. Those who wish to join the tour must also be naked. Adults only.) 2011-ongoing.

Photograph: Christo Crocker/National Gallery of Australia

The dignified halls of the National Gallery of Australia 전시in Canberra are an unconventional space to wear your birthday suit. But here we are, on Wednesday evening, 50 art lovers disrobing with quiet, private trepidation.

I too begin to strip: the dress comes off, the underwear soon after – until I stand, breasts, bum and bush in the breeze.

I shuffle nervously. There is nowhere to hide.

When the gallery announced it would be running nude tours of its blockbuster retrospective of the American light artist James Turrell, the scoffing editorials followed. The Guardian’s Jonathan Jones said there was “something arrogant about Turrell’s desire for people to be at their most exposed”.

But hasn’t the nude always belonged in the gallery? Arcing back to ancient prehistoric civilisations, and rarely losing its foothold in popular western art, from Michelangelo’s robust David to the stark confrontation of Lucian Freud’s flesh-filled paintings.

Granted, the naked art spectator is a less common sight, but as our tour guide for the evening, Stuart Ringholt, tells it (he too in the nude), the white cube of an art museum is already a “reductive space”– so it follows that clothes are a kind of visual noise disrupting our experience.

“Minimal museum, minimal audience and James’s work is very minimal,” he says. “Put these three things together and it seems quite appropriate.”

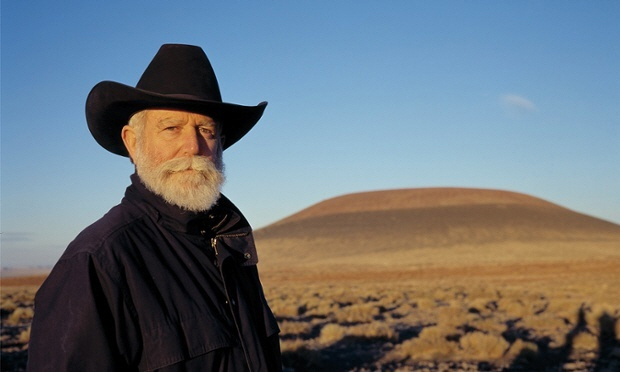

James Turrell in front of Roden Crater in the Arizona desert. With the help of astronomers, the artist turned the crater into a naked-eye observatory. Photograph: Florian Holzherr

Australia is not the first country to run a naked tour of Turrell’s work. In Japan viewers had the option of entering his Perceptual Cell – a single-person capsule that blasts the spectator with coloured light – without clothing. And Ringholt himself has been running nude tours since 2011 as part of his own art practice in Melbourne, which delves into the psychology of embarrassment and humiliation. So when the show came to Australia, Turrell decided the two experiences could make a good fit.

Being naked is a kind of “reset”, says Ringholt. “We’re at our happiest when we’re nude: we take a bath when we’re nude, we sleep sometimes when we’re nude, make love when we’re nude. We swim in the ocean or we run through the park – and they’re our most wonderful times.”

Turrell, meanwhile, believes our bodies have an intimate relationship with light that we frequently overlook. Earlier in the year he told Benjamin Law in the Monthly that “light is part of our diet”.

“We drink light as vitamin D through the skin,” he said. “Without vitamin D, we have serious problems in the serotonin balance and you get depression. Light is a food.”

Bodily modesty has always struck me as the most stupid of human hang-ups. In June, my editor asked me to participate in a mass nude swim as a bitingly cold solstice dawn broke over Tasmania’s Long beach. Which makes this the second naked story I’ve been assigned on the job. For Law, this is the third time an editor has requested he strip off. I suspect the Australian media establishment has a secret Asian fetish.

Before we reach Turrell’s retrospective we have to walk through the main halls of the gallery, a surreal experience in itself. There is something naughty – in a childish sense – about tiptoeing through such a grandiose institution, past the Sidney Nolans and the Aboriginal Memorial, with so many boobs and dicks swinging around like pendulums.

Stuart Ringholt leads his naked tour, standing in front of James Turrell’s 1969 work Raemar pink white. Photograph: Christo Crocker/National Gallery of Australia

That feathery ticklishness I experienced when first undressing in public is vanishing – I feel more comfortable in my skin with each step. But it’s not until we reach one of Turrell’s works that it hits me why we are here. Why art – something we appreciate through our eyes, sometimes our ears, but rarely with our entire bodies – can suddenly be transformed by this absurd act of nudity.

Raemar pink white (1969) is deceptively simple. On paper, it reads like mere decor: a rectangular stripe of pink light glowing from a hidden source. But once you’re in front of it, the shape is so large it fills your entire field of vision, until it seems to warp and wrap around your entire body.

Without a thread between my body and the work, my bare flesh seems to be drinking all that peppy pink brightness in. The feeling is sensual, not sexual. I’m acutely aware of the cool air on my skin, a lock of hair resting on my shoulder. Everyone around me is gawping at the art, almost euphoric with delight.

We’re all looking at each other’s bodies too, of course, but neither intensely nor with furtive snatched glances. It’s the sort of cool appreciation encouraged by a Degas painting: a woman stepping into a bathtub, towel drying one lifted arm, captured in her natural state. “I show them stripped of their coquetry, in the state of animals cleansing themselves,” the painter once said.

Stuart Ringholt leads his nude tour through the National Gallery of Australia. Photograph: Christo Crocker /National Gallery of Australia

Whether we like it or not, our clothes announce which tribe we belong to. Without them we are reduced to a bowl of human fruit: colourful but lacking in pretension. Our tour group are a kind of still-life and I spot nourishing food everywhere; a marbled pink leg, the warm pear-curve of hips, wobbling jelly bottoms and fried egg nipples. Every body its own shape, size and in a state of decay – marvellous yet utterly ordinary.

John Cocks, participant and president of the ACT Nudist Club, (yes, that’s his real name) explains to me the difference between exhibitionism and nudism. “An exhibitionist is someone who gets excited about being naked in front of somebody else or having themselves seen naked by somebody else,” he says. “There’s a titillation aspect to it. For a nudist, being nude means you can relax – you accept people as they are. I just like to be free.”

Since he was a “little tot”, Cocks has disliked wearing clothes, and at 61 he is unlikely to change his tune. “That’s what most people have a problem with. They associate nudism with [something] sexual. You don’t see somebody without their gear on unless you’re going to jump into bed – that’s the way we’ve been taught. ‘Nude is rude.’ But it’s not. It can be a natural way.”

Naturists use the term “skyclad” to describe the feeling of being nude. This evening we are “artclad” and for Cocks and his naturist cohort, the tour is a rare opportunity to practise outside the privacy of their own homes and the club’s bushland property. “With most people the biggest problem with going nude in public is actually that first step,” he says. “When you take your clothes off, a few minutes into it you don’t notice any difference.”

But for the vast majority of participants here tonight – a mix of men and women of varying ages, all adults and all obliged to be nude – the tour marks their first time practising public nudity and many say it has been a transformative experience.

Student Sarah Hanlin, 24, felt a growing apprehension in the days leading up to the tour. On the drive up to Canberra from Melbourne she ran through the scene of undressing in her head, and it struck her: where would she put her hands? “You know when you’re nervous you sort of just put your hands in your sleeves, tug on something, put them in your pockets?” she says.

Earlier in the evening her nerves continued to jangle as she undressed – was she doing it in the right order? should she be sitting down? – until finally, she was naked. How did she feel? “I sort of reclused for a while.” She still hadn’t figured out what do with her hands, and told herself: “Don’t put them on your hips because everyone will know you’re shy. Stand, look. Don’t look. Look blank and act normal.”

Despite her misgivings, Hanlin quickly warmed to the experience. “Such a lovely vibe,” she says. Her favourite piece was Sight Unseen from Turrell’s 2014 Ganzfeld series, where spectators enter a scooped-out space drenched in coloured light whose furthermost wall appears invisible.

Not transparent, simply not there. To me, being naked in that space felt like skinny-dipping in the void. Hanlin describes it as “swimming in a pool of light”.

“If I’d had clothes on, the light would have been affected. It was incredible.”

• James Turrell: A Retrospective is at National Gallery of Canberra until 8 June 2015

FAMILY SITE

copyright © 2012 KIM DALJIN ART RESEARCH AND CONSULTING. All Rights reserved

이 페이지는 서울아트가이드에서 제공됩니다. This page provided by Seoul Art Guide.

다음 브라우져 에서 최적화 되어있습니다. This page optimized for these browsers. over IE 8, Chrome, FireFox, Safari