Do Artist Branding and Hollywood Talent Agency Deals Kill an Artist's Soul?

Paddy Johnson, Tuesday, February 17, 2015

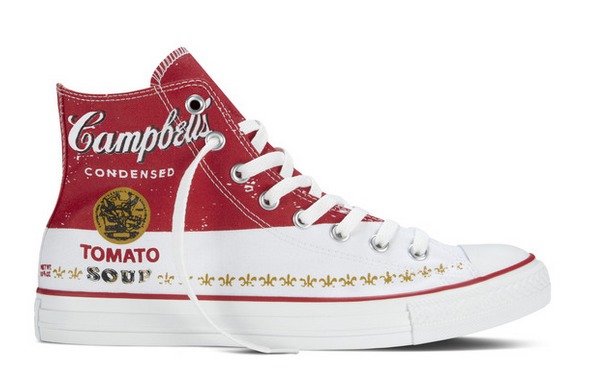

Andy Warhol x Converse

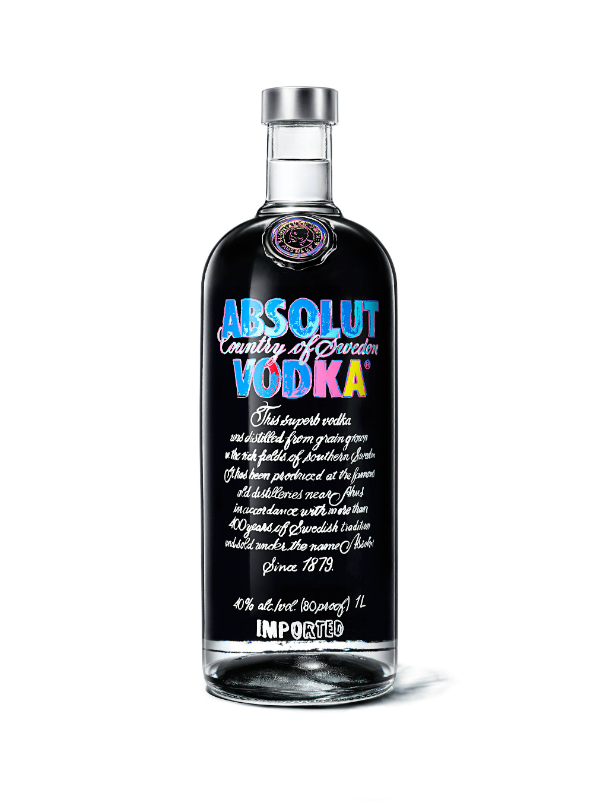

We've all seen the Andy Warhol Converse sneakers (read Converse x Andy Warhol Coming in February). And the Uniqlo t-shirts adorned with famous artworks. And the painted BMW cars, and the artist's branding of Vodka bottles. But here's a question: If artists want to put their signature squiggles on a shoe or a bottle of booze, are they compromising their work in exchange for a bit of cash?

That's the fear of many now being discussed on Facebook thanks to the news that at least one Hollywood talent agency wants to get into the art game. Last week, the Beverly Hills–based United Talent Agency announced the formation of a new visual art wing in its company (see Hollywood Agency Announces Plans to Represent Visual Artists — Guess Who?). The company is primarily known for representing actors like Johnny Depp and Angelina Jolie. They would help broker sponsorship deals and assist artists who want to become more involved in the movie-making business.

A collection of threatened gallery owners, when interviewed, said they did not expect the company to do well. No surprise there. Who wants more competition? Dealer and collector Stefan Simchowitz has complained over Facebook, where he seems to spend most of his working day, that “contracts kill art" (read he believes the United Talent Agency experiment is doomed). Internet artist and professor Marc Horowitz has also chronicled his four-year dysfunctional relationship with William Morris that began back in 2006. “Whatever energy and originality I had, they figured out a way to scar it, kill it, stretch it out and make it something that was no longer mine," he remarked ruefully. His story sounds no different than that of any Hollywood script writer I know.

I don't agree with Simchowitz on the subject of contracts—legal documents exist to make the responsibilities of both parties clear, and without them business relationships easily get messy. There's no reason that a contract with, say, a shoe company, has to result in art's murdered soul. Why would it? You are just signing a piece of paper. Trying getting a home loan and see what that's like. Does that kill an artist's soul?

The Andy Warhol Absolut Vodka limited edition bottle

Photo via: F&B News

Same goes for some corporate branding deals. I, for one, quite like the Jenny Holzer shoes “Protect Me From What I Want" produced for her retrospective at the Whitney, even if they were a bit tacky. I'm sure a contract was signed. But to Horowitz's point, it's also true that corporate sponsorship deals easily go awry. Just last year, Marina Abramović's remake of a performance from her 1970s series “Work Relation" for the sportswear giant Adidas made waves for its stupidity. In the original performance, she divided workers in trench coats into groups performing various methods of carrying stones to learn which method was the most effective. The answer: a human chain works best because it involves teamwork! That said, this is probably one art performance that could stand to be lost within the annals of art history because, well, it's kind of pointless and in this instance overly literal and commercial-minded. In the remake, she chooses 11 performers to match the number of players in a soccer team and everyone of course wore Adidas shoes…. The piece was so dumb and so pandering that internet commenters responded in the only way they knew how: by attempting to identify the earliest date Abramović jumped the shark.

Suffice it to say, nobody wants to see more sell outs along the lines of Abramović. Generally, though, I don't see a problem with merchandising deals. When Jeff Koons paints a car for BMW, I don't assume it's a core part of his practice, in the same way that when Drew Barrymore poses for the cover of Vanity Fair, I don't re-evaluate her skills as an actor. They are simply means for creatives to make more money. And assuming United Talent Agency hires a few art-savvy folk to manage their accounts—they're off to a good start by hiring Joshua Roth, an art lawyer, to head the division—this may represent more opportunities for artists. There's nothing wrong with that.