정준모

Market United Kingdom

Year in review: six things you need to know about the art market

Changes were amplified, directions were unpredictable and the future is clouded

By Georgina Adam. Focus, Issue 263, December 2014

Published online: 22 December 2014

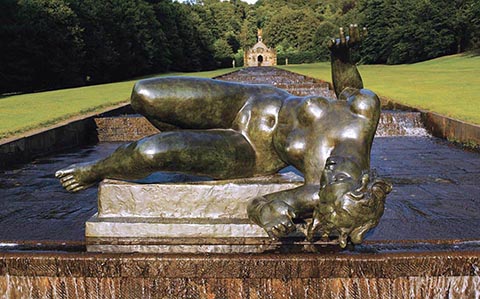

One of the works offered by Sotheby's at its annual show at Chatsworth House

This has been a year of increasing disruption in the art market. While its vastly increased value over the past ten years (€47.4bn in 2013 compared to €18.6bn in 2003, according to the latest Tefaf report by Clare McAndrew) has inevitably brought change, 2014 has seen those changes magnified and evolving in directions that were not previously predictable.

One of the most striking aspects is the way auction houses have been expanding their businesses in a constant bid to cover all revenue-generating bases. Much has already been written about their move into private selling, both as part of their in-house operations and through dedicated retail outlets—Christie’s has just increased its New York space—which mainly feature secondary market material, but a few of the shows organised in the auction houses’ new dedicated galleries also included work consigned directly from artists.

This has been happening notably in Sotheby’s and Christie’s selling spaces in Hong Kong, with another example being Sotheby’s ongoing annual exhibitions of monumental sculpture at the British stately home Chatsworth, which also include some work consigned directly from artists’ studios.

Penetration of the primary market

Penetration of the primary market would be the last frontier, allowing auction houses to achieve a stake in all aspects of the art chain, from production of a work of art to the final resale. An earlier attempt at Christie’s to do this via the acquisition of a dealer, Haunch of Venison, ended in failure, and that lesson has certainly not been lost on Sotheby’s. The firm must also have reflected on the one highly public experiment in selling directly from the studio (Damien Hirst’s London auction in 2008). Although it appeared to be a success at the time, it then resulted in a drop in Hirst’s prices and desirability in the following years. It certainly would be logical for the auction houses to see their private selling spaces as a potential vehicle for moving more strongly, but less publicly, into the primary market at some future date.

Auction houses and the internet

The auction houses’ move into the internet is another disruption. Sotheby’s, probably under pressure from the activist investor-and-now-board-member Daniel Loeb, has linked up with eBay. Christie’s has gone a step further with e-commerce—it is now offering “click and buy” options on watches and some items from sales of collectibles, in advance of the actual auction. Again, a sign that the top houses—which describe themselves as “art businesses” or “the art people”—are continuously seeking ways of extending their reach by entering the online marketplace as players themselves.

Made-for-the-market mania

As for dealers, their traditional modus operandi is being disrupted in other ways. What is often called the “Leo Castelli” model, when a gallery slowly developed an artist’s career and was rewarded along with his or her success, is under threat, and not only because of the immense firepower of the Megagosian galleries. Poaching of artists has been exacerbated by the arrival of speculators such as Stefan Simchowitz, the “art flipper”, and those he advises, who can make an artist’s reputation and force up prices extremely rapidly. It was striking, at the contemporary art sales in London in October, that a number of the younger artists’ works on offer were made just two or three years before, and one in 2013 in the case of a Lucien Smith at Sotheby’s.

There are two disruptive aspects to this: first, the effect on the artist’s career. An explosive price rise and rapid transition to auction leaves artists with the challenge of what to do next: continue making the successful works, or risk being quickly written off by exploring new, and possibly not such saleable, avenues. Second, these almost overnight success stories encourage poaching, with some artists quickly moving up the gallery food chain—again, disrupting the traditional model. And, sadly perhaps, the phenomenon of speculation seems to have triggered a breed of artists opportunistically producing made-for-the-market works, often process-based abstraction, or as the critic Jerry Saltz colourfully puts it, “crapstraction”.

Finally, the “Leo Castelli” model is also being weakened by globalisation: artists may well be represented by a number of galleries in different countries, a situation which inevitably impacts on the artists’ and the galleries’ mutual commitment.

Fairtigue

Disruption has also affected art fairs. Until very recently, it was possible for collectors to visit all the main events, but with the explosive growth of the number, and their geographical spread, it has become very difficult for even the most determined globe trotter to take them all in. The term “fairtigue” has been much used but for good reason: collectors have become more selective, and the very homogenisation of the top fairs does nothing to change this. The same applies to art galleries—apart from the very major players, who have the financial and human resources to exhibit at sometimes a dozen fairs a year, most art dealers have been forced to be more strategic in deciding which to attend.

Seal of approval

Also increasingly problematic is the fair versus gallery programme conundrum, which has not yet been resolved. Fairs represent a large, and increasing, part of a gallery’s turnover, as well as being the “seal of approval” conferred by selection for Basel, Frieze, the Armory or Fiac. That selection is based on the gallery’s programme, but since resources, certainly for the mid- and small-sized dealers, are limited, attending fairs plus running a respected gallery programme puts considerable strain on the gallery’s finances. In addition, selection for a top fair may depend on the galleries agreeing to exhibit work or artists who are not necessarily the most easy to sell, so cutting off a source of income.

And finally, again for all but the biggest galleries, art fairs can represent a considerable risk: the takings from one may well be needed to finance the next one. If the fair goes badly, or a deal falls through, this can have a devastating impact.

Booming emerging economies

Finally, the impact of growth economies is inevitably disrupting the market. Rumours that Bonhams might be bought by the Chinese Poly Auction group have not been confirmed, but a deal such as this would have been inconceivable just a few years ago. The Chinese auction houses are beginning to extend their reach outside their home base, bringing new buyers, new tastes and new ways of working into the market. In the long term, this may prove to be the biggest disruption of all.

• Georgina Adam is the author of Big Bucks: The Explosion of the Art Market in the 21st Century (Lund Humphries, 2014)

FAMILY SITE

copyright © 2012 KIM DALJIN ART RESEARCH AND CONSULTING. All Rights reserved

이 페이지는 서울아트가이드에서 제공됩니다. This page provided by Seoul Art Guide.

다음 브라우져 에서 최적화 되어있습니다. This page optimized for these browsers. over IE 8, Chrome, FireFox, Safari