정준모

Artists Exhibitions USA

Critic's pick of the top ten shows of 2014

From Malevich to Jeff Koons: Blake Gopnik chooses his highlights

By Blake Gopnik. Focus, Issue 263, December 2014

Published online: 22 December 2014

The New York art critic on the best shows of 2014

1 John Gerrard

John Gerrard’s Solar Reserve (Tonopah, Nevada), installed on the plaza of New York’s Lincoln Center in October, was that very rare thing: high-tech art that went beyond techie spectacle. Gerrard’s giant LED screen used video-game software to give us a lifelike view of a solar-power installation in Nevada, presented in a simulation of live video. The piece was truly spectacular—no passerby could resist it—but also seemed to seed doubts about the virtues of its own technology. Could the solar technology it seems to sell really ever keep up with our endless hunger for screens and the power that drives them? Even when used to make art, does gaming software ever leave behind its roots in the world of first-person shooters?

2 Kazimir Malevich

I almost skipped the Kazimir Malevich survey that opened at Tate Modern in London in July, because I felt that I’d already seen more than enough to have grasped what he and his art were about. The exhibition proved me wrong. Its early rooms made me realise how talented Malevich was from the very start: even when he was working in a Nabis or Impressionist style, his derivations could compete with works by those movements’ founders. The exhibition’s wonderful recreation of the 1915 gallery where Malevich showed his famous Black Square made me understand for the first time how that work never represented an end-point for Malevich, as though extreme reduction had been a principle he was working towards. He was no Donald Judd or Robert Ryman: he continued to make complex, maximalist paintings and sculptures even after he’d arrived at the minimal.

3 Christopher Williams

For some reason, “Christopher Williams: the Production Line of Happiness”, at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York in July, seemed to strike many smart critics as pretentious—deliberately obscure and recherché. It’s true that some of the rhetoric around Williams’s meta-photographic practice can be impacted, but the works themselves strike me as a wonderfully telling exploration of the ins and outs of our image culture. That makes them necessarily as complex as that culture, but never for the sake of the complexity itself. Let’s pause to remember that most deeply original Modern art, from Cézanne to Picasso and beyond, was first thought to be needlessly recondite.

4 Jeff Koons

At the Whitney Museum of American Art in June, curator Scott Rothkopf organised the perfect Jeff Koons retrospective. Whether you love or hate Koons, could any critic deny that his excellence (or weakness) got an ideal outing in Rothkopf’s show? I happen to think that Koons has often achieved something I wouldn’t have thought possible: he’s taken the Duchampian ready-made in genuinely new directions, and injected it with emotions—even politics—we might not have thought it could carry. Yes, Koons has made many lame works (all the later paintings, most of the giant stainless-steel tchotchkes) but I don’t think his batting average is much worse than, say, Rubens or Picasso.

5 Here and Elsewhere

“Here and Elsewhere” at the New Museum, which opened in June, was a worthy exercise from the get-go, bringing to New York an unprecedented spread of art from the Arab world. It went way beyond the worthy, however, in its presentation of the self-portraits of the Cairene photographer Van Leo, made during and after the Second World War. In the photos at the New Museum, we got to watch him restage himself as a daredevil pilot, religious ascetic and gunman, heading deep into Cindy Sherman territory many decades before anyone else got there. In the end, all such “ethnic” shows are really remembered for the particular treasures they turn up; this one turned up some stunners.

6 13 Most Wanted Men

In an age when even the richest museums can seem addicted to empty, crowd-pleasing shows, it was a special pleasure to visit “13 Most Wanted Men: Andy Warhol and the 1964 World’s Fair”, a collaboration between the Queens Museum in New York and the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. Warhol’s silkscreens of petty criminals came at one of the great moments in his career, and explore some of his crucial concerns: seriality, gay desire, social conformity, the human face. This show let us dig deep into all the circumstances of the project’s creation. It reminded me of “Picasso: Guitars 1912-1914” at MoMA in 2011. That’s the highest praise I can give.

7 Amy Siegel

Amie Siegel’s elegant and witty video Provenance, which I caught at the Metropolitan Museum in New York in June, was a lovely study in how objects become art. The video’s first shots show the Chandigarh armchairs of Le Corbusier where they now sit, as official treasures, in billionaires’ yachts and homes. Then Siegel’s footage tracks them back through the entire supply chain—of auction houses, dealers, restorers and antique pickers—all the way to the chairs’ origins as cast-offs in the office buildings that they were designed for in the Punjab. The piece was especially pungent at the Met, our official end-point for officially sanctioned art

8 Kara Walker

Kara Walker’s A Subtlety, a 75ft-long sphinx coated in sugar, was on view for May and June at the decommissioned Domino Sugar Factory in New York. It was great to see Walker moving on from her trademark silhouettes, and responding so well to a specific site and commission. Her sphinx had a lovely mix of humour and threat—like that Halloween special of a treat with a razor inside. It’s a rare mix for any work of public art.

9 Charles James

In May, the Metropolitan Museum launched “Charles James: Beyond Fashion”, its survey of some of the greatest gowns and dresses of the first half of the 20th century. There is nothing more lame than using the terms and frameworks of fine art to describe what goes on in the very different world of fashion. But what can I say? My first thought about these outfits were that they were Brancusis in cloth. Maybe my second thought redeems me: at least one of the gowns was so explicitly clitoral that it seemed to address the politics of desire in a way that only a dress ever could.

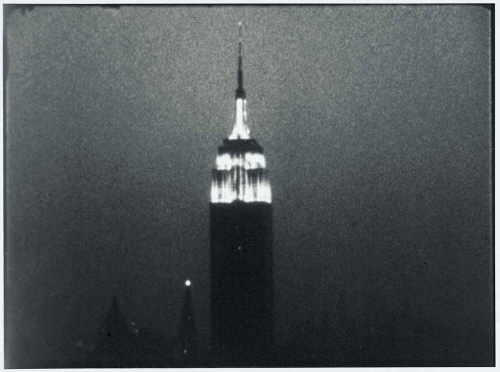

10 Empire

Can we judge a show’s success by the time we spend in it? How about seven hours straight? In January, when the James Fuentes gallery in New York screened Warhol’s Empire, uncut and in its original 16mm, I viewed the entire masterpiece without a break, watching the light change on the Empire State Building from sunset to about 2.30am. The piece deserved the marathon, in that it is clearly one of the landmarks of experimental film, and of the passage of such films into fine art. It also demanded it: seeing a few minutes of Empire is like glimpsing a few corners of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon and thinking you’ve seen the whole thing. Empire lasts the duration of a blue-collar factory shift; to truly understand the piece, you need to re-enact Warhol’s labours in shooting it.

• Blake Gopnik is working on a biography of Andy Warhol for HarperCollins

Kara Walker's A Subtlety, 2014

In January, James Fuentes gallery in New York screened Andy Warhol's Empire, 1964, uncut and in its original 16mm

http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/Year-in-review-critics-pick-of-the-top-ten-shows-of-/36374

FAMILY SITE

copyright © 2012 KIM DALJIN ART RESEARCH AND CONSULTING. All Rights reserved

이 페이지는 서울아트가이드에서 제공됩니다. This page provided by Seoul Art Guide.

다음 브라우져 에서 최적화 되어있습니다. This page optimized for these browsers. over IE 8, Chrome, FireFox, Safari