정준모

A New Art Capital, Finding Its Own Voice

Inside Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Abu Dhabi

By CAROL VOGELDEC. 4, 2014

The architect Frank Gehry talks about his asymmetrical design for the planned 450,000-square-foot Guggenheim Abu Dhabi and his inspiration for the museum’s huge, cooling cones. Video by Channon Hodge on Publish Date December 4, 2014. Photo by Gehry Partners.

ABU DHABI, United Arab Emirates — The site of the future Guggenheim Abu Dhabi is desolate these days: just arid land and concrete pilings jutting out over a peninsula on Saadiyat Island, north of the city’s urban center here. But in about three years, it is poised to become an international tourist attraction, when a stunning museum designed by Frank Gehry, a graceful tumble of giant plaster building blocks and translucent blue cones, is scheduled to open.

Spanning 450,000 square feet, the $800 million museum will be about 12 times the size of the Guggenheim’s Frank Lloyd Wright landmark in New York and will showcase art from the 1960s to the present. The collection is being assembled from scratch by Guggenheim curators following a “transnational” template, with popular symbols of American culture like Andy Warhol’s Brillo boxes or Richard Prince’s photographs of the Marlboro Man juxtaposed with works by artists from China, Asia, India and the Middle East.

Part of a $27 billion cultural and tourism initiative, the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi is one of three museums under construction that are being financed by the government of Abu Dhabi, capital of the United Arab Emirates. A branch of the Louvre, designed by Jean Nouvel, is opening next year. And the Zayed National Museum, lionizing a former ruler, designed by Norman Foster and created with the British Museum as a consultant, is expected to open its doors in 2016. Local officials bristle when asked about importing big Western brand names and expertise.

The Guggenheim Abu Dhabi will be 12 times the size of the landmark Guggenheim museum in New York. To fill it with art, the curators first plan out the space with scaled-down models and tiny silver people. Video by Channon Hodge on Publish Date December 4, 2014. Photo by Channon Hodge/The New York Times.

“We have to begin somewhere,” said Zaki Anwar Nusseibeh, a cultural adviser at the emirates’ Ministry of Presidential Affairs. “We know we cannot create culture overnight, so we are strategically building museums that in time will train our own people, so we can find our own voice. Hopefully, in 20 or 30 years’ time, we will have our own cultural elite, so our young people won’t have to go to London or Paris to learn about art.”

Mr. Nusseibeh pointed to the success of the Guggenheim Bilbao, which was paid for by the government of the Basque region of Spain and has been attracting about one million visitors a year since it opened in 1997.

An “infinity mirrored room” by Yayoi Kusama. Credit Karim Sahib/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

As recently as the 1950s, Abu Dhabi was little more than a cluster of tiny villages and date farms populated by fishermen, pearl hunters and nomadic Bedouins. It wasn’t until the advent of oil production in the 1960s that the emirate got its first paved roads; later, hospitals and schools arrived.

Hanan Sayed Worrell, the Guggenheim’s senior representative in Abu Dhabi, stood overlooking the Guggenheim’s site on a 106-degree afternoon. “Ten years ago, there was nothing here,” she said.

Richard Armstrong, director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and Foundation. Credit Richard Perry/The New York Times

Before 2006, “you would have had to come by boat,” she added. “There wasn’t a road or bridge. There was nothing but sand.”

A lot has happened in the eight years since the government of Abu Dhabi announced the project. There was the worldwide economic downturn of 2008 and the Arab Spring. There were also changes of leadership within the Tourism, Development and Investment Company, the government-run developers who are overseeing the museums. Between economic fears and political unrest, by 2012 work on the museum projects had frozen. “All the pilings were in, and then everything just stopped,” Mr. Gehry recalled. “Everybody was silent.” A year ago, he said, he heard from a new group at the development company that was determined to see the projects through.

Reem Fadda, an associate curator, says that while there are institutions that honor Arab and Middle Eastern art, the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi will place the work of Arab artists side by side with that of their international counterparts. Video by Channon Hodge on Publish Date December 4, 2014. Photo by Channon Hodge/The New York Times.

More recently, the region has been at the center of a worker-abuse scandal, focused in particular on the New York University campus in Abu Dhabi, which was built by migrant laborers who were forced to live and work under unspeakably harsh and abusive conditions. Fearing that history might repeat itself, the group Gulf Ultra Luxury Faction has led several protests at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, waving banners that call for fair labor practices.

Richard Armstrong, director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, who said he sees establishing a branch in Abu Dhabi as part of the museum’s worldwide mission, added that he was “deeply committed to fair labor issues.” Although a contractor for the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi has not been selected (a decision, officials there say, is imminent), the government of Abu Dhabi, through the development company, has already hired Pricewaterhouse Coopers to oversee the construction, which is expected to start next year, enlisting monitors to keep watch over the project.

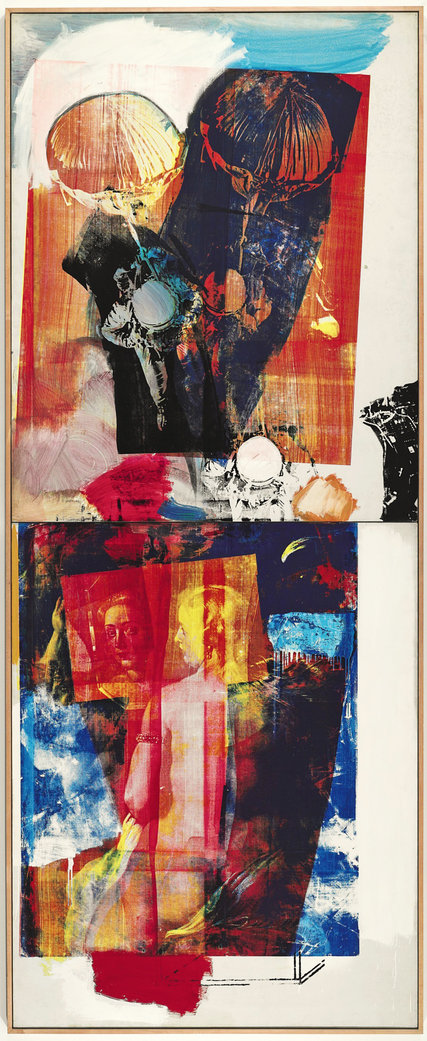

Robert Rauschenberg’s “Trapeze” (1964). Credit Robert Rauschenberg Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Even before the protests, Mr. Gehry said, he was contacted by Human Rights Watch. “I spoke to the emirates,” Mr. Gehry said in a telephone interview. “And they’re concerned about it, too. We’re going to make sure everything is done properly. We’re trying to move the needle.”

Unlike Doha (Qatar’s capital) — whose royal family has enlisted top flight advisers and spent what is rumored to be more than $1 billion to build a masterpiece collection including works by Cézanne, Picasso, Rothko, Twombly and Damien Hirst for its network of museums — Abu Dhabi has been modest in its acquisitions. While no one at the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi will talk officially about money, people close to the museum say they have a budget of about $600 million with which the curators, in collaboration with local officials, have so far purchased about 250 works.

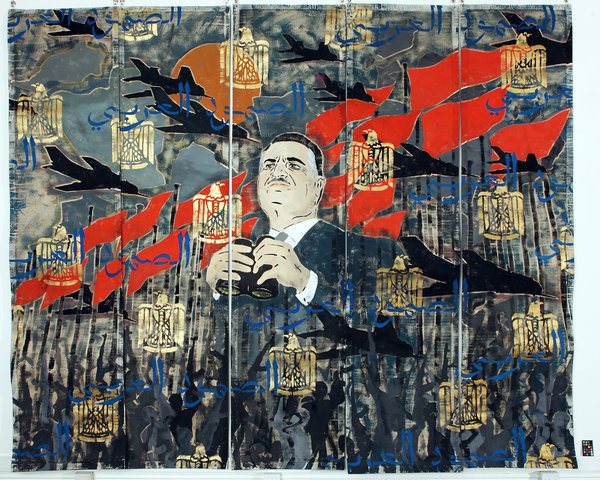

Chant Avedissian’s “The Arab Resistance” (2008) Credit Rose Issa Projects

The curators’ goal has been to be inclusive in a way that will resonate with Abu Dhabi’s changing population and its visitors. About 10 million tourists came to the region last year, Mr. Armstrong said, with the local airport undergoing a major expansion so that by 2017, it will be able to handle an estimated 45 million passengers a year arriving there from Africa, Asia, India and Pakistan. There is also a large local population not used to having museums in their backyard, according to Sandhini Poddar, an adjunct Guggenheim curator based in London, who is working with the curatorial team. The challenges are “how to make a collection that speaks to these art histories, to places like India, Pakistan, Asia, in a respectful, intelligent and elucidating way.”

“It will take one or two generations before a museum like the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi will soak into the quotidian part of life,” she said. “This is not just entertainment and spectacle but art, education, beauty, and it will take a while to feel internalized and natural.”

“Andy 1962-63,” Marisol’s tribute to Warhol, complete with a pair of his shoes. Credit Acquavella LLC/All rights reserved Marisol Escobar, Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

To address this melting pot of cultures, Mr. Armstrong said, he and his curators have been forced “to get away from the bipolarity of seeing art history from the point-of-view of America and Europe.”

Even when construction was frozen in Abu Dhabi, curators in New York were forging ahead. Instead of calling the museum global, which they say connotes money rather than art, they describe it as transnational, to reflect “the rich fabric of information being shared among cultures in the Middle East,” Mr. Armstrong said.

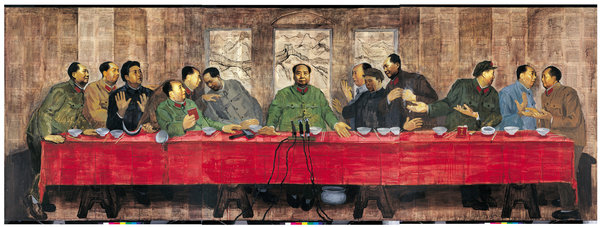

Mao Zedong plays host in Zhang Hongtu’s “Last Banquet” (1989). Credit Zhang Hongtu

Tucked in the back of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s offices in SoHo, there is an open space that at first glance looks like a preschool playroom. There are models the size of giant doll’s houses made up of futuristic shapes and miniature galleries hung with diminutive replicas of artworks from the new collection.

“We’re working against type,” said Nancy Spector, the Guggenheim’s deputy director and chief curator. “We’re telling an alternative art history, weaving different stories together. It’s more nuanced than just buying work by a lot of big names.”

The museum itself will consist of four levels of galleries, the first primarily for the permanent collection and the others dedicated to special exhibitions. The museum will also have different kinds of spaces, including giant exterior cones that provide shade for visitors. Mr. Gehry said he had devised them after spending time in the Middle East. “I noticed that even though it’s hot, the men tended to hang out outdoors because the air-conditioning is so strong,” he said. His system of cones, somewhat like a tepee, vents hot air out the top. Eventually, he said, the curators plan to commission site-specific artworks within the cones. “It’s a big building, and the audience is not used to going to art museums,” Mr. Armstrong said. So the galleries will be organized thematically. There will be spaces that introduce visitors to abstraction and others that tell the story of figuration. There are also galleries that will explore key ideas that make up conceptual art and another to delve into the way artists during the 1960s drew ideas from history in ways that reflected their own cultures.

The curators have included big names in contemporary American art: Warhol, Rauschenberg, Richard Prince, Frank Stella, Donald Judd, Jeff Koons and James Rosenquist. But there will also be a significant focus on artists from the Middle East and Asia who are largely unfamiliar to American and European visitors. “We are finally breaking loose from that fixation of Europe and North America,” Mr. Armstrong explained.

“Seeing Through Light: Selections From the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi Collection,” an exhibition of 19 artworks intended for the new museum, opened last month at Manarat, a visitor center on Sadyiaat Island, where thousands got their first glimpse of the collection. It explores artists’ use of light and includes one of Yayoi Kusama’s “Infinity Rooms,” a blackened galaxy of water and mirrors lit by minuscule handblown LED lights; a hanging light ball by Otto Piene, of the German Zero group, and a bronze sculpture by the Egyptian-born artist Ghada Amer, along with work by California artists like Doug Wheeler, Robert Irwin and Keith Sonnier, who experimented with light and space in the 1960s and ’70s.

Light is only one narrative in the collection. Valerie Hillings, who is leading the Guggenheim’s curatorial team, explained that she and her fellow curators had been grappling with different ways to tell interconnected stories, like how artists in various parts of the world were playing with themes like celebrity portraiture and consumerism.

Alongside work by Western Pop stars like Claes Oldenburg and James Rosenquist will be art by Chant Avedissian, an Egyptian who marries images of Arab resistance with Ottoman textile patterns. His portrait “The Arab Resistance” features a photograph taken around the time of the Six-Day War, showing Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt’s second president, looking through binoculars as if contemplating the future as he surveyed the Arab world. Another painting, by the Egyptian artist Adel El-Siwi shows the singer Om Kalthoum with a gold-painted face like a Renaissance Madonna.

“These are as iconic as any Warhol,” Ms. Hillings said. Also on display will be “The Last Banquet,” by the Chinese artist Zhang Hongtu, a panel painting with Mao at the center. The collection also includes a wooden chair with a portrait of Warhol painted by Marisol, the French artist. “This portrait is made all the more real because it includes a pair of shoes that actually belonged to Andy Warhol,” Ms. Hillings said.

“We’re trying to look at popular culture across time and space,” she added. “These are different points of reference, yet each is universal.”

Correction: December 7, 2014

An earlier version of this article misidentified a group that has led worker-abuse protests at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. It is Gulf Ultra Luxury Faction, not Human Rights Watch.

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/07/arts/design/inside-frank-gehrys-guggenheim-abu-dhabi.html?_r=0

FAMILY SITE

copyright © 2012 KIM DALJIN ART RESEARCH AND CONSULTING. All Rights reserved

이 페이지는 서울아트가이드에서 제공됩니다. This page provided by Seoul Art Guide.

다음 브라우져 에서 최적화 되어있습니다. This page optimized for these browsers. over IE 8, Chrome, FireFox, Safari