정준모

The Problem With Selling the Largest Private Art Collection in the World

By James Tarmy Jul 16, 2014 4:26 AM GMT+0900

Source: Courtesy of Art Basel

Monika Sasnowska's 'Untitled' from The Modern Institute Gallery.

Source: Artist Pension Trust Global via Bloomberg

Moti Shniberg in New York City, 2010.

Moti Shniberg shuffles through the lobby of the trendy Manhattan building where his company is based to a quiet corner table. A boyish 41-year-old with red hair and a soft Israeli accent, he’s slightly out of place among the dressy-casual office workers who weren’t yet in high school when he launched the Artist Pension Trust, which may hold the largest private collection of contemporary art on the planet.

“Look around,” Shniberg says, gesturing to the walls. “You see all the art there? All of these are APT artists.” And who created the video installation in the corner? “I’m not sure,” says Shniberg, half sheepish, half defiant. “We have so many artists.”

Close to 2,000, from 75 countries, they have collectively contributed 10,000 artworks to the trust, a unique combination of artist collective and hedge fund. Shniberg has attracted big-name backing as well, all by promising to fix what is widely viewed as a broken market: Those who create art -- even valuable art -- often don’t profit from it nearly as much as their collectors or even, on occasion, their own dealers. Shniberg's solution is a combination of skipping the middleman (artists get to bypass their dealers by selling through APT instead) and altruism (part of each sale goes to other artists).

It’s a sound strategy on paper, and over the past decade Shniberg has corralled an impressive amount of art.

Now, to sell it.

Shniberg, whose background is in data-mining tech startups, secured backing from investors such as Thomas Schimdheiny, the fourth-wealthiest man in Switzerland, Sir Harry Djanogoly, a prominent British philanthropist and art collector, and Raymond McGuire, the head of Global Banking at Citibank, investing on his own behalf. The trust's advisory board includes Lady Elena Foster, chairman of the Tate International, and John Baldessari, an iconic conceptual artist, along with a host of curators spread across the globe who recommend artists for the trust.

Twenty years ago, the Artist Pension Trust would have been inconceivable. The art market wasn’t yet a repository for sums so large they appear to be made up. In 1993, the top-grossing living artist at auction, according to Artnet, was the pop artist Roy Lichtenstein. His art sold that year for a total of $3.9 million, or $6.3 million in today’s dollars. Last year the painter Gerhard Richter held the same title. His total auction sales: $189 million.

With this much money sloshing around there seems to be some for everyone. And that includes, as Katya Kazakina has reported, art-market speculators like Stefan Simchowitz, who made a small fortune by finding and promoting the art of 20-somethings to his famous friends and then reselling it at tremendous profit.

This would be fine, except that artists don’t get any royalties from secondary sales. Instead, they depend on galleries, which play the role of agents and managers, generally taking 50 percent of the sale prices. Galleries try to avoid letting art slip into the auction market too early, if at all.

'Your relationship with your gallery has a lot to do with how they protect you,' says Liam Gillick, a contemporary artist represented by the Casey Kaplan gallery in New York, who has invested his work in APT. 'One of the key ways that they protect you is to keep you from being used as a kind of exchange object -- being bartered around.'

When everything works as it should, artists and galleries benefit from an artist’s career in equal measure. But sometimes things go wrong. Collectors get greedy and try to flip the art to other collectors, or go broke and dump the art for less than it’s worth. Artists can only watch as their work gets volleyed around.

Enter Shniberg, who stepped into this morass of artistic endeavor and capitalist ferment in 2004. At the time, he was a technology entrepreneur based in Israel who had just sold ImageID, a pattern recognition firm. He was also setting the groundwork for his next ventures, filing for a series of patents and trademarks.

One patent was for facial recognition technology, and formed the basis of Face.com, a company that Shniberg co-founded and sold to Facebook in 2012 for $60 million. Another effort was a trademark on the term “Sept. 11, 2001” (filed on September 11, 2001, and rejected a few years later) and its use in various forms of entertainment, including TV dramas, news shows, theater productions and “musical variety, news and comedy shows.” Shniberg says he filed for the trademark for “charitable purposes.”

He also founded Mutual Art, an art-information website that compiles huge swaths of data about artists (exhibitions, news articles, auction sales) and allows subscribers to play around with that data to create indexes. Most recently he founded FDNA ('the most beautiful company I've done in my life,' he says), a software company that uses facial recognition technology to assist in genetic research.

All of these ventures, except for the peculiar September 11 trademark attempt, use fickle, nebulous sets of data to create something intelligible and lucrative. Mutual Art assembles seemingly disconnected pieces of information to lend insight into an artist’s career trajectory. You can click on a Performance button and presto, a median price performance index of an artist's sales is charted alongside industrywide median auction results. Shniberg takes raw data, in other words, and makes it available to the masses, effectively democratizing information previously available to a select few.

Here's how APT works.

Artists around the globe are invited by a board of curators to join their own regional pool with 249 other artists. The eight regional pools cover the biggest art markets: New York, Los Angeles, Dubai and so on. There's also a global pool with a capacity of 628 artists.

By joining, an artist agrees to donate 20 of her own works to the pool over 20 years. Members have usually achieved some level of commercial success; the recommended base retail price for work they donate is $5,000. The trust waits at least a decade after a work is donated to sell it.

Having just reached its 10th birthday, APT has started to sell (so far, less than 1 percent of the collection), in a process likely to accelerate in the coming years. Forty percent of the net proceeds of the sale go to the artist. Twenty-eight percent go to APT. The remaining 32 percent goes into the pool and is distributed evenly among all of the artists.

The trust is structured in such a way that if the artist’s career takes off, she has set aside works that will let her share in the profits. If her career lags, she can reap the benefits of her peers' success.

The current value of the trust’s art collection, Shniberg says, is around $125 million. Based on the existing commitments of future donations by APT artists, Shniberg says, its value is closer to $500 million. He says the trust’s worth will “double, at least” in the next four years.

Beyond the star-studded board, Shniberg hired the blue-blooded Pamela Auchincloss as director of the New York pool, and then a host of young curators as far apart as Puerto Rico and Mumbai to search out artists and recruit them to contribute their art. He partnered with Dan Galai, recently the dean of Hebrew University’s business school and the father of what has become known as “portfolio theory,” which uses risk management to optimize investment profits. They’re joined by Shniberg’s stable of investors, who pay for the considerable costs of storing and marketing APT artworks.

But the backers aren’t the only ones taking a risk.

'You're basically allowing this institution to quasi-represent you,' says Charlie Friedman, an artist who has invested in the APT global pool. 'You want to make sure that it stays protected -- that the work gets marketed in a way that's appropriate.”

There's the added fear that, in an effort to generate cash, APT could tank an artist's market by dumping the work all at once. 'There's the worry that they might liquidate my work in some way that's beneath its value,' says Kevin Cooley, an artist who has invested in the APT New York pool. He worries that his artwork could be bundled with a group of other artists and sold in bulk. “There’s no indication for how that’s going to go,” he says.

Shniberg brushes those concerns aside. 'We have to be sensitive to an artist's career, and sensitive to their price,' he says. 'Remember, our clients -- our investors -- are the artists.”

Those clients are about to find out if they’ve made a good investment.

“It’s laudable that someone is making such a big move,” says Marion Maneker, editor of the Art Market Monitor, an art trade publication. “But also somewhat breathtaking that they’re taking such an enormous risk without anyone having done something like it before.”

APT’s success hinges on three factors: whether the trust’s body of artwork rises in value, whether the trust can sell that body of work at the peak of its value and whether there are enough collectors to buy everything APT wants to sell.

The first of these hurdles is probably the easiest to surmount. Most of the artists in APT’s portfolio will never be particularly valuable. “There’s an enormous amount of art produced and sold,” says Maneker. “The vast majority of it, once sold, will never have an exchange value again.”

For APT that’s fine; they factored that into their risk structure. The scale of the trust guarantees that at least some of its pools have artists with a resale value. Some estimates predict that only 3 to 5 percent of APT's art has to double for the trust to work as needed.

The second problem, of timing the sale, is tougher. APT started with a rule that it would hold every artwork donated to the trust for at least 10 years. The rule was presumably put in place to eliminate competition between the trust and its artists’ galleries: neither would ever find the other selling prints from an artist’s edition at the same time.

But 10 years is a long time in the contemporary art world, long enough for a contemporary artist to no longer be, well, contemporary. The artist Douglas Gordon, for instance, who has invested his work in APT and is represented by the powerful Gagosian Gallery in New York, reached a median sales price of over $50,000 at auction in 2008. Much of his art is a combination of video and installation art. “Play Dead, Real Time,” which is now in MoMA’s permanent collection, consists of two giant projectors and a smaller monitor displaying a silent video of a circus elephant.

It’s a famous work, and Gordon is an established artist. His median sales price in 2013, however, was just $15,643. In other words, Gordon’s sales price might have peaked already. As APT begins to liquidate its collection, it might find that it has missed the prime earning years of artists.

In an email, Virginia Coleman, a spokeswoman for the Gagosian Gallery, wrote, “We don’t comment on prices, but have a healthy primary market for Douglas Gordon and place his work regularly in the best museums and private collections in the world.”

APT’s last problem, of demand, is the most difficult. Selling art requires connections. Shniberg clearly has links to people with deep pockets, but that’s not the same thing as having access to a swath of collectors willing to buy 10,000-plus art objects, some of which are room-size installation pieces. Even established collectors might be a little hesitant to buy a homemade, 10’ x 20’ pine bleacher covered in “found textiles” accompanied by a dissonant soundtrack and the message “Come in friends, the house is yours!” spray-painted on a nearby wall. Selling something like that requires finding and seducing a buyer who has the right combination of sensibility, money and exhibition space. For some works, that buyer may not exist.

This is potentially befuddling for an outsider looking into the art world. As money gushes in and fairs sell untold billions of dollars of art, prospective buyers must seem infinite. But there’s no public square where an artist can simply plunk down his wares and wait for offers to pour in. Instead, the current structure is creaky, antiquated and heavily weighted against the artists themselves. Shniberg, riding in on his data-driven horse, showed that there must be a better way, that the art market was yet another unruly data set waiting to be tamed and groomed and presented for the world to enjoy.

But unlike Shniberg’s other projects, APT’s success probably isn’t a question of mastering information. Instead, the entire operation just might depend on his ability to curry favor with the very people his organization claims to bypass: dealers. It’s there that he can find answers for what art to acquire, when to sell and whom to sell to.

In other words, to conquer the art market, Shniberg, the soft-spoken outsider, might have to become its biggest insider instead.

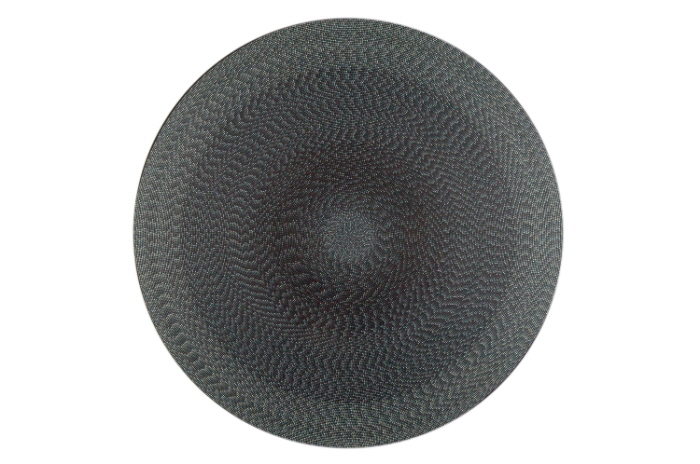

Source: Courtesy of the artist and Artist Pension Trust

Michelle Grabner's 'Untitled' (2006) from the APT Collection.

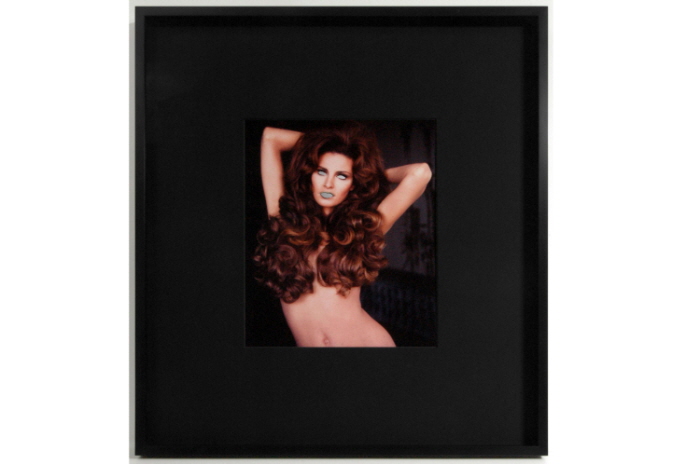

Source: Courtesy of the artist and Artist Pension Trust

Douglas Gordon's 'Self Portrait of You and Me' (2007) from the APT Collection.

FAMILY SITE

copyright © 2012 KIM DALJIN ART RESEARCH AND CONSULTING. All Rights reserved

이 페이지는 서울아트가이드에서 제공됩니다. This page provided by Seoul Art Guide.

다음 브라우져 에서 최적화 되어있습니다. This page optimized for these browsers. over IE 8, Chrome, FireFox, Safari