정준모

Exhibitions Conservation USA

Not fake, but ‘tarted up’

Painting due to be removed from museum wins reprieve after tests prove it is a genuine Old Master

By Emily Sharpe. Conservation, Issue 258, June 2014

Published online: 27 June 2014

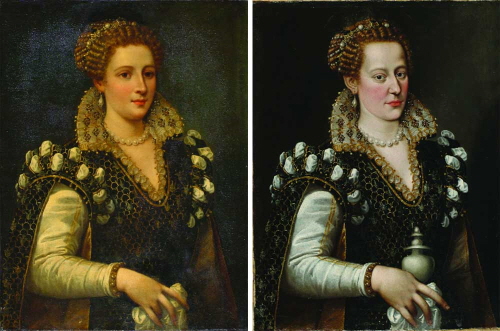

Isabella de Medici, before treatment (far left) and when the restoration was almost finished

A painting that was “targeted for removal” from the collection of the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh won a last-minute reprieve after a technical examination determined that it was not a “modern fake”, but a 16th-century Florentine portrait that was significantly “tarted up” in the 19th century.

“I was convinced it was a total modern fake,” says Lulu Lippincott, the institution’s curator of fine arts, referring to what was purportedly a portrait of Eleanor of Toledo by the Italian Mannerist Bronzino. “One look at the picture and I thought, ‘you’ve got to be kidding—this is not a Bronzino’,” she says. Convinced that the work was not the Old Master it claimed to be, Lippincott sent the picture to the conservation studio with a note asking Ellen Baxter, the museum’s chief conservator, to confirm that it was a fake.

Baxter’s response, however, was not what Lippincott expected. “I wasn’t too sure, because on the surface it appears to be a painting with crack patterns that are wrong for a painting on canvas. Something just didn’t fit,” Baxter says. But she did agree that the sitter’s Victorian biscuit-tin features did not resemble other works by the artist. When she examined the painting’s stretcher, she found the metal stamp of Francis Leedham, a prominent 19th-century British restorer who was skilled in transferring paintings from panel to canvas. “Finally the history of the work was jiving with what we were seeing,” Baxter says, explaining that the crack pattern was consistent with what she would expect to find on panel paintings. She thinks that the work was transferred to canvas because the panel had a split that could not be repaired.

Lippincott then had to accept that the work was at least 100, if not 400, years older than she originally thought. “That’s when the fun really began,” she says.

The real breakthrough came when X-rays revealed an altogether less glamorous figure hidden beneath the surface: an older, jowly woman with “droopy eyes and hands that [were made to play] basketball”, Baxter says. X-rays also showed traces of a halo and revealed that the woman originally held an alabaster urn; both are attributes of Mary Magdalene. The sitter’s face and hands were probably painted over in the 19th century, after the work was transferred to canvas, to make the piece more saleable. Lippincott traced the painting to the 19th-century railroad magnate and art collector Collis Potter Huntington, who bequeathed the bulk of his collection to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The Carnegie acquired the picture in 1978.

Lippincott focused on the woman’s clothing—the most authentic part of the painting—to help identify the sitter. Searching through a catalogue of paintings of the Medici family, she spotted the woman’s dress in a portrait of Isabella de Medici (1542-76), the free-spirited daughter of Eleanor of Toledo and Cosimo de’ Medici; she was strangled by her husband after he learned of her affair with his cousin. Lippincott believes that the picture was painted around 1574, and that the halo and urn were added shortly after the work was completed. The Mary Magdalene attributes transformed the portrait into a “symbol of repentance”; Isabella’s brother Francesco, who became head of the family in 1574, was less accepting of her scandalous lifestyle. “This may have been Isabella’s attempt to clean up her act,” Lippincott says.

Removing the overpaint was fairly straightforward, Baxter says. “I removed 130-year-old paint on top of 400-year-old paint, and you can’t get much more stable than that.”

They hope that the removal of the overpaint will enable them to identify the artist. Lippincott thinks that the work is by someone from the circle of Alessandro Allori, the leading painter of the Medici court during the 1560s and 1570s. “Now that we have the picture as close to its original appearance as we can, scholars will be able to make an accurate assessment of its quality and authenticity,” she says.

The portrait is one of five works due to go on display this month in an exhibition at the museum.

The real deal or made for American millionaires?

When the portrait of George Neville, the third Baron Bergavenny (below), came onto the market in the 1920s, it was proclaimed to be a lost painting by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-1543), made after a drawing at Wilton House, the country estate of the Earl of Pembroke. However, contemporary scholarship has downgraded the “Old Master” to a 19th-century copy made for the American millionaire art market, after tests showed that the paint used for the background dates to the late 19th or early 20th centuries.

But recent tests focusing on the sitter’s face show that the “colours are indicative and representative of the period of Hans Holbein the Younger”, says Ellen Baxter, the chief conservator at the Carnegie Museum of Art, which acquired the work in 1967. Baxter thinks that the background was heavily overpainted and that the earlier test—the results of which have been lost—was restricted to the overpaint layer and “didn't dive into the juice of the painting underneath”.

The museum was planning to conduct further tests as we went to press. The portrait is due to be included in the institution's “Faked, Forgotten, Found” show.

“Faked, Forgotten, Found: Five Renaissance Paintings Investigated”, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, 28 June-15 September

FAMILY SITE

copyright © 2012 KIM DALJIN ART RESEARCH AND CONSULTING. All Rights reserved

이 페이지는 서울아트가이드에서 제공됩니다. This page provided by Seoul Art Guide.

다음 브라우져 에서 최적화 되어있습니다. This page optimized for these browsers. over IE 8, Chrome, FireFox, Safari