정준모

Don't call Glasgow's contemporary art scene a miracle

Glasgow has produced three of this year's Turner Prize nominees, and several previous winners. This should come as no surprise

Moira Jeffrey

The Guardian, Saturday 10 May 2014

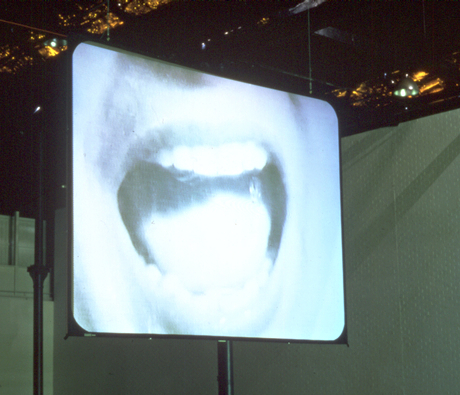

A still from Douglas Gordon's video installation 24 Hour Psycho.

When the Turner prize shortlist was announced this week, the news that three out of four of this year's nominees studied at Glasgow School of Art was no great surprise for Glaswegians. Tris Vonna Michell studied for an undergraduate degree there, while Ciara Phillips and Duncan Campbell both undertook the two–year postgraduate programme, the MFA, there.

In recent years the city has come to dominate Turner prize lists. Glasgow winners include Douglas Gordon (1996), Simon Starling (2005), Richard Wright (2009) and Martin Boyce (2011). Martin Creed (2001) and Susan Philipsz (2010) both studied and made their careers elsewhere, but grew up in the city. I could go on: nominees Christine Borland, Jim Lambie, Nathan Coley, Cathy Wilkes, Lucy Skaer, Karla Black, Luke Fowler andDavid Shrigley have all lived and worked in Glasgow.

"Of course you guys will win it," a television news editor said to me when, as a journalist, I was covering the 2011 prize. "The Turner prize belongs to Glasgow." This week Ben Luke of the London Evening Standard echoed him. The shortlist, he wrote, "confirms the supremacy of Glasgow as the UK centre for new art".

The question is why? How has a declining post-industrial city, with practically no art-collector base, with important historical collections but skeletal contemporary institutions, become so culturally dominant in the UK and, indeed, in Europe?

The answer is, perhaps, simple: why not? Douglas Gordon was only the most prominent of a new generation of artists who had graduated from Glasgow School of Art and had nothing to lose. In the west of Scotlandthe dwindling days of Thatcherism and the Major years were economically and politically grim. But if money felt scarce, this generation were culturally – if not financially – ambitious and opportunistic. In 1991 a group of artists staged Windfall '91, an exhibition in a former Seamen's Mission on the banks of the River Clyde. In the catalogue, artist Ross Sinclair roused his fellows: "Doors lie open all over the world," he wrote. "All it takes is for us to go through them."

This summer, more than 60 galleries and museums across Scotland are hosting Generation, a programme of exhibitions that is part of the nationwide Glasgow 2014 cultural programme. It will include the work of more than 100 artists who came to prominence in the country in the last 25 years. I have been editing a book, the Generation Reader, of new essays and archival material, and have found that many of them scratch away at the secrets of Glasgow's success.

The writer Sarah Lowndes, whose book Social Sculpture is a chronicle of Glasgow's rise to prominence, has linked the city's artistic culture to its notable night life – she draws a line from postwar dancehalls to rave culture to the thriving independent music scene. David Harding, the influential Glasgow School of Art teacher whose innovative environmental art course nurtured many generations of students, suggests that conviviality helped build a supportive community. The novelist Nicola White, who in her former career as a curator commissioned Douglas Gordon's breakthrough artwork 24 Hour Psycho (1993), cites "the collective, egalitarian feel of Glasgow, the multitude of practices and groupings, the respect for hard work, the 'now'". All of them agree that the do-it-yourself culture of the city's artists, who built their own institutions rather than rely on established ones, has been crucial.

Then there are the technological advances of the last quarter-century: the mobile telephone, cheap air travel and, of course, the internet. Once you needed to live in New York for your work to be seen there. Now we have Skype and are a cheap flight away from colleagues in Berlin or Cologne. There is structural change: the commercial art world does business at international art fairs such as Frieze. Glasgow has a tiny commercial gallery sector and few collectors. Artists make their work in Glasgow and if they sell it, do so elsewhere. Art fairs make that possible. But, crucially, commerce is not all. Many thriving spaces and events are artist-run and voluntary. Even the city's key dealer Toby Webster, now one of the UKs most important gallerists, grew up with his roster of artists as a peer and fellow artist.

Webster's gallery the Modern Institute is minutes from the studios of his artists. Glasgow is a smallish city, with a motorway cutting right through its heart. The modern consequence is that most people live 20 minutes from the airport. It's vitally important to understand that these days Glasgow artists are an international community: Ciara Phillips was born in Canada, Duncan Campbell in Dublin; both stayed on in the city after education, buoyed by its possibilities. Glasgow has always been outward looking: a mighty river runs through it. Its built fabric is Victorian and very grand. Rents are considerably cheaper than in many major UK cities and the city council, which once appeared wrongfooted by the riches on its own doorstep, has now invested hugely in studio complexes. For those who work at home, and many Glasgow artists do, the architecture of the Glasgow tenement is a godsend. Tenement living offers large rooms, high ceilings and huge windows that routinely make my London friends gasp. All this takes us only so far. The bottom line is that artists get nominated for the prize because they are recognised as good. Australian curator Juliana Engberg, who included a number of Glasgow artists in this year's Sydney Biennale, stresses that artists routinely alert her to their colleagues: one studio visit leads to another. Artists learn from, share with, and are challenged by their peers.

Skaer, a Glasgow School of Art graduate who was nominated for the Turner Prize in 2009, grew up in Cambridge. "On my first visit to Glasgow, aged 18, I saw Douglas Gordon's 24 Hour Psycho at Tramway," she has said. "Since then, my experiences here cannot be untangled from the language and influence of my precedents and peers. It's the creative fabric of the place." Skaer recently returned to live and work in the city after seven years in London and New York. When Martin Boyce thanked his teachers from the Turner prize podium in 2011 he said he meant his friends and fellow artists as much as his lecturers.

Living in Glasgow, one finds oneself torn between a certain sense of pride and mild outrage that people are surprised that the city's cultural life has deep roots and international reach. The Glasgow art scene is far more complex – and sometimes more fraught – than headline news and big prizes. Most of Scotland's artists maintain international careers with an underlying economic fragility. Judicious public support has underpinned achievement.

The two most hated words in the Glasgow art world lexicon are "Glasgow Miracle", a term coined to describe the city's success. Once it was resented because it seemed to deny the long, hard and unpaid labour behind cultural achievement. These days it seems even more foolish because it suggests a momentary flash in the pan. Glasgow's success is hard won, durable and above all consistent. It is 18 years now since Douglas Gordon won the Turner Prize, and jokingly thanked his friends in the "Scotia Nostra". You would think that the rest of the country would have had time to get used to it.

• This article was amended on 10 May 2014. The standfirst initially stated that Glasgow was the capital of Scotland.

FAMILY SITE

copyright © 2012 KIM DALJIN ART RESEARCH AND CONSULTING. All Rights reserved

이 페이지는 서울아트가이드에서 제공됩니다. This page provided by Seoul Art Guide.

다음 브라우져 에서 최적화 되어있습니다. This page optimized for these browsers. over IE 8, Chrome, FireFox, Safari