정준모

큐레이팅이란 참으로 어려운 것입니다. 작품에 대한 이해와 시대에 대한 생각 그리고 전시하는 공간에 대한 이해가 맞아떨어져야 하는 것이지요.

하지만 우리에게는 전시보다는 진열 진짜 디스플레이만 있는 것이라는 생각이 듭니다. 늘 어려운 전시를 만들고 잘난체를 하는 한스 울리히지만 그가 만드는 전시의 근본이 충실하게 기본, 소위 정상적인 전시를 염두에 두고 그에 기초해서 별종 또는 변종을 만들어 내고 있다는 점에서 곰곰 읽어보아야 할 것 같습니다.

피터 쉘달(Peter schjeldahl, 1942~ )에 의하면 오늘날의 미술관은 모든 미술품을 우상으로 주조하도록 한 결합 백과사전형

즉 국립중앙박물관이나 국립현대미술관 같은 미술관을 비롯해서 하우스형, 도시형, 부티크형, 파빌리온형, 실험실용, 유원지형으로 구분합니다.

오늘날 대한민국의 미술관은 모두가 대중화라는 명분으로 유원지형을 지향합니다. 참으로 애석한 일입니다. 서로가 자신의 역할과 기능에 대해 최대한 자신감을 가지고 줏대있게 나아가는 미술관을 희망해 봅니다.

-

Hans Ulrich Obrist: the art of curation

Behind every great artist is a great curator. But what do they actually do? Serpentine superstar Hans Ulrich Obrist reveals the delights and dangers of his craft – while Yoko Ono, David Shrigley and more pick their all-time favourite show

Hans Ulrich Obrist. Interviews by Stuart Jeffries and Nancy Groves

The Guardian, Sunday 23 March 2014 15.59 GMT

'One of my favourites' … Adrian Piper's The Humming Room, part of Do It

Hans Ulrich Obrist

One of my childhood heroes was Sergei Diaghilev. He didn't dance. He wasn't a choreographer. He didn't compose. He didn't direct. But he was, to use a term the writer JG Ballard said to me in an interview, a junction-maker. Diaghilev was the founder of the Ballets Russes: he brought Stravinsky together with choreographers, with Picasso, Braque, and Cocteau. He made art meet theatre meet dance.

Diaghilev and Cocteau tried to explain what they did with the words: 'Etonnez moi!' Astonish me. I've never had an art practice, and I've never thought of the curator as a creative rival to the artist. When I became a curator, I wanted to be helpful to artists. I think of my work as that of a catalyst – and sparring partner.

It's worth thinking about the etymology of curating. It comes from the Latin word curare, meaning to take care. In Roman times, it meant to take care of the bath houses. In medieval times, it designated the priest who cared for souls. Later, in the 18th century, it meant looking after collections of art and artifacts.

There's a hangover of all those things in modern curating. When I curated my first exhibition – which followed discussions with the artistsFischli/Weiss (Swiss duo Peter Fischli and David Weiss), Richard Wentworth, Christian Boltanski and Hans Peter Feldmann in the kitchen of my apartment in St Gallen, Switzerland – I had a productive misunderstanding with my parents. They thought I was going into medicine because curating means caring. I don't think they thought it was to do with art.

Today, curating as a profession means at least four things. It means to preserve, in the sense of safeguarding the heritage of art. It means to be the selector of new work. It means to connect to art history. And it means displaying or arranging the work. But it's more than that. Before 1800, few people went to exhibitions. Now hundreds of millions of people visit them every year. It's a mass medium and a ritual. The curator sets it up so that it becomes an extraordinary experience and not just illustrations or spatialised books.

I started going to exhibitions in Switzerland when I was 10 or 11. As a schoolboy, I would go every afternoon to see the long, thin figures ofGiacometti. I'd just look and look. As Gilbert & George told me: 'To be with art is all we ask.' But the first epiphany I had in terms of curating came when I saw Harald Szeemann's Der Hang zum Gesamtkunstwerk (The Tendency Towards the Total Work of Art) in 1983. Szeemann had the idea of the exhibition as a toolbox, or of an archaeology of knowledge, like Michel Foucault. That is how Szeemann displayed works by Gaudi, Beuys, Schwitters and others: the idea was that these artists had created all-embracing environments. I went to see that exhibition 41 times.

Later, I was inspired by how philosopher Jean-François Lyotard curated the 1985 exhibition Les Immatériaux at the Pompidou in Paris. It dealt with how new information technologies shape the human condition, but what interested me was that, rather than writing a book, Lyotard made his philosophical ideas into a labyrinth in the exhibition. It's difficult to describe because he was producing the idea rather than illustrating it, but it influenced me and lots of other artists – like Philippe Parreno, who I worked with later.

But there are dangers with curating. The Gesamtkunstwerk exhibition was very dense, very inspiring and interesting because of the danger that it became the Gesamtkunstwerk of the curator rather than of the artists. But for me, it was important to be close to artists and not subordinate their work to the curator's vision. I've realised that the curator's role is more that of enabler. The Italian conceptual artist Boettitold me to pay attention to artists' unrealised projects. Many artists have not been able to realise their fondest projects. My role is to help them.

One of my favourite exhibitions is called Do It, which I co-curated with the artists Christian Boltanski and Bertrand Lavier 21 years ago. It is still going. It was inspired by Marcel Duchamp sending instructions from Argentina to his sister to assemble one of his readymades, and by John Cage's music of change, and by Yoko Ono's work. Lots of artists contributed how-to instructions to do things in the gallery or elsewhere. It's been to more than 120 cities, often to places where there isn't otherwise much of a contemporary art scene. Right now, it's in Salt Lake City. It can continue for the next 100 years.

Joseph Beuys talked about expanding the notion of art. I'm trying to expand the notion of curating. Exhibitions need not only take place in galleries, need not only involve displaying objects. Art can appear where we expect it least. • Hans Ulrich Obrist is co-director of the Serpentine Galleries. His Ways of Curating is published by Allen Lane.

David Shrigley

Sonic Youth's art show in Malmo.

The exhibition that really sticks in my mind was the Sonic Youth show from maybe two or three years ago that toured. It was curated by Sonic Youth and Robert Groenenboom. I had a piece of work in it and caught it in Malmö. What struck me was the fact that there was a lot of bad art in it, yet it was still fantastic. A lot of stuff wasn't art, or was art but by dilettante artists, but somehow it fitted together well.

It was all about Sonic Youth, their relationships with other artists and with art. There were so many different types of work. Some exhibits were more like artefacts. In fact, the magic was in the blurring of art and artefacts, of artists and musicians. Their journey, that was the premise. So they had the Sonic Youth album covers made by some seminal artists: Gerhard Richter, Christopher Wool, Mike Kelley. They even had their final album cover, which was designed by John Fahey. He was the quintessential folk revivalist. He made these paintings that he'd sell at his gigs.

The show made you realise that that's what curating is: it isn't necessarily about showing good art to its best advantage. It's about making an exhibition that's really good. You can make a good show without having good art in it. That's not to say you can't have both, just that it's possible without both.

My eyes glaze over when people want to talk about curating. I think good curation is working with someone who can do something you can't. That goes for any good collaboration. The best is when you're making a show together and finding it all out as you go along. Some curators are academics, but artists aren't – or at least I'm not.

Yoko Ono

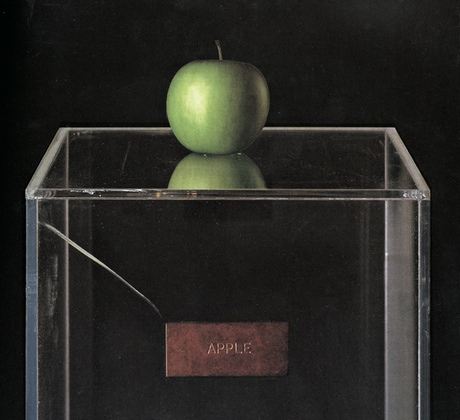

Apple by Yoko Ono Photograph: Tony Cox

When I do a show, I'm hands on. I almost do the whole thing myself. Over the course of my career I've been lucky to work with many creative curators. Their role is to give me protection and encouragement. Not in the sense of changing what I do, but allowing me to do what I want to do. They have helped me to understand what I like.

Alexandra Monroe gave so much love to me and my work that she madeYes [Ono's first major retrospective] very easy for me. I would sometimes wonder why she would select a particular work - but she says: 'Look at this – it's important, Yoko.' And she is often right.

Jon Hendricks [curator of Ono's current Bilbao show] has also been very supportive – just by going to places on my behalf and saying: 'Yoko doesn't like that.'

Hans Ulrich is one of those people who jump around a lot. He flies around in his mind, just as he is always flying around the world. And when you meet that mind in transit it's very exciting. It gives me a sense of my own power. My feeling is that Hans is not just a curator. His duty is to nurture his own knowledge and tastes as much as the artists he works with.

John Baldessari

Yves Klein in the late 50s Photograph: Express Newspapers/Getty Images

The collector Virginia Dwan had a remarkable gallery in LA, which later moved to New York. She was instrumental in exhibiting many European and New York artists who had never shown on the west coast before. The show I most remember was Yves Klein at Dwan Gallery in the late 60s: it was all blue paintings. It made me rethink what I was doing. Virginia had to close the gallery in the end. She wasn't making a profit. The message is that it wasn't about selling art.

I think a good curator is like a good chef. They understand the city's needs – and fulfil and challenge them. How do curators and artists work with each other? Ideally, it's a collaboration in which one inspires and challenges the other. The best thing a curator can do is elicit the response, 'I didn't know you could do that,' from the public. The worst thing is to present a show that is no longer relevant.

Mark Wallinger

Tue Greenfort's Diffuse Eintraege, part of the Münster Sculpture Project in 2007 Photograph: Roman Mensing

The Münster Sculpture project was founded by Klaus Bussmann and Kasper König in 1977 and happens every 10 years. Kasper has been the curator throughout. It's an amazing project and I was lucky enough to be part of it in 2007 – one of 33 artists that year.

My work was to encircle the city with this thin line that was barely visible. I remember having a meeting in a Münster cafe with Kasper where I said: 'I want the circle to go around here but I need a set of compasses or something.' Kasper just lobbed a saucer across the table, I drew around it and half an hour later we were in the town council office with the chief surveyor asking me how many metres above sea level I wanted it.

Kasper is a sounding board and an enabler and an enthusiast for all the artists he works with. Münster is a personal place for him. It's not like those shows where international curators get dropped in. His relationship to the city is critical to the whole venture.

Taryn Simon

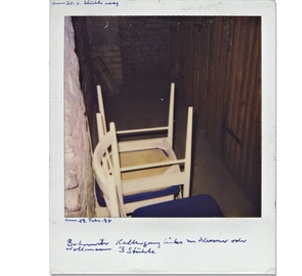

Untitled by Horst Ademeit

The exhibition that stands out for me is Horst Ademeit at the Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart in Berlin, 2011. In a small, often overlooked area of the museum was an overwhelming amount of meticulously ordered material by an artist I'd never heard of before. After being rejected by his parents, his wife, his school, and even his teacher – Joseph Beuys – Ademeit abandoned drawing and painting for photography and writing. He shot more than 6,000 Polaroids in isolation over a 14-year period, which engulfed the room.

In the margins of the Polaroids, and in seemingly endless calendars and booklets, he handwrote notations at a scale that borders on indecipherable. He was studying the impact of cold rays, earth rays, electromagnetic waves and other forms of radiation on his health and safety. He protected himself with magnets and herbs from what he perceived to be dangerous invisible forces, while obsessively creating this trove of records and evidence. The exhibition felt almost like an invasion of privacy — as if you were seeing somebody's secret world.

Philippe Parreno

Les Immateriaux. Photograph: Centre Pompidou

I was really influenced by early shows at the Pompidou, particularly Les Immatériaux, curated by Jean-François Lyotard in 1985. One of the first to imagine our digital future avant la lettre, it was enormously influential, its title reflecting not just a shift in the materials we use, but also in the very meaning of the term 'material'.

Lyotard created an open structure, a maze with one entrance and one exit, but multiple pathways through it. Walls were not solid structures but grey webs stretching from floor to ceiling. Visitors wore headphones and listened to radio transmissions that faded in and out as they moved through the exhibition. Such fluid non-linearity exemplified the very conditions of immateriality central to the show's argument.

What makes for a good curator? Passion, curiosity, intelligence. Hans, Daniel Birnbaum (director of the museum of modern art in Stockholm) and I are working on a project: the sequel Lyotard planned to Les Immatériaux, which never took place. Ours is called Resistances. Humans want to simplify events in the world in order to understand them. For example, it's easier to say that the force of gravity is stable but actually it's not. It oscillates. Lyotard believed that art was about that, about resistant forces that make things not totally how we think they are. That's a really beautiful way to define art and art curating.

FAMILY SITE

copyright © 2012 KIM DALJIN ART RESEARCH AND CONSULTING. All Rights reserved

이 페이지는 서울아트가이드에서 제공됩니다. This page provided by Seoul Art Guide.

다음 브라우져 에서 최적화 되어있습니다. This page optimized for these browsers. over IE 8, Chrome, FireFox, Safari