Getty presents first major museum exhibition to focus entirely on Gustav Klimt's drawings

LOS ANGELES, CA.- —Drawing the human figure was Gustav Klimt’s starting point for exploring overarching themes of existence—the cycle of life, human suffering, happiness, love, and longing. Gustav Klimt: The Magic of Line, Drawings from the Albertina Museum, Vienna, on view at the J. Paul Getty Museum July 3, 2012 through September 23, 2012, is the first major museum exhibition devoted entirely to the modern master’s drawings.

Klimt (Austrian, 1862–1918), the father of Viennese modernism, is renowned for his ornate paintings, but he was also an exceptionally innovative and gifted draftsman. Featuring more than 100 drawings, many having never before been exhibited in North America, this exhibition traces Klimt’s radical evolution from early academic realism and historical subjects in the mid 1880s to his celebrated modernist icons that broke new ground in the beginning of the 20th century.

This major loan exhibition was organized by the Albertina Museum, Vienna, in partnership with the J. Paul Getty Museum, to mark the 150th anniversary of Klimt’s birth (July 14, 1862). Throughout 2012, the city of Vienna will celebrate this anniversary with special events and exhibitions in the region, including the exhibition at the Albertina, which houses one of the world’s most comprehensive collections of Klimt drawings.

“Working with our colleagues at the Albertina, the Getty is proud to bring this first major exhibition of Klimt’s drawings to the U.S.,” said James Cuno, president and CEO of the J. Paul Getty Trust and acting director of the Getty Museum. “In looking at four decades of drawings by Klimt, this exhibition reveals how he tackled line, space and the human figure, developing into one of the most distinctive, seminal figures in Modernism. It is precisely the kind of exhibition for which the Getty has earned its international reputation.”

Early Work

This thorough chronological examination of Klimt’s drawings begins with those made in his early style of Historicism—popular in the 1880s—that depicted grand historical and mythological scenes in a realistic manner. From its earliest moment, Klimt’s art was based on drawing the human figure from life, as it would be for the rest of his career.

“Gustav Klimt drew live models nearly every day,” explains Lee Hendrix, senior curator of drawings at the Getty Museum. “His drawings are essential to understanding Klimt’s art and give crucial insight into his creative process. They demonstrate his search for aesthetic solutions as well as his ongoing concern with the transitory, interconnected, and ineluctable flow of human existence.”

In the mid-1890s, Klimt’s approach to the figure gradually became more ambiguous both formally and psychologically with modeling and perspective abandoned in favor of the flat plane of the paper or canvas. At the same time, the wider European movement of Symbolism began to influence Klimt’s work, as he rejected optimistic, unambiguous historical subjects and began to investigate troubling psychological and emotional worlds of dreams, melancholy, and sexual desire.

The Vienna Secession

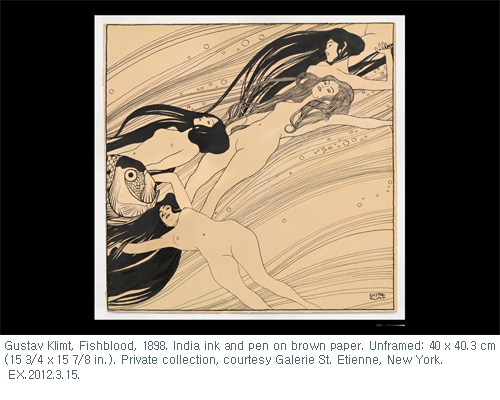

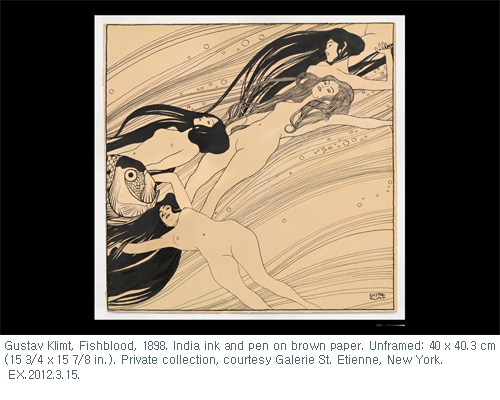

In 1897, alongside other young Austrian artists and architects, Klimt broke away from the Vienna “Artists’ House” (Künstlerhaus)—the exhibition venue dominated by academically established painters. Calling themselves the “Secession,” the group sought to revolutionize the visual arts in Vienna. At this time, Klimt took up Symbolism more fully and developed dreamlike themes, including the floating female figures that became a recurring motif in his work. The figures are often cropped at the feet and hands, which heightens the sense that they are floating in space, while paradoxically anchoring them on the page. This section of the exhibition features masterpieces of Klimt’s graphic art, such as the large drawing Fish Blood, made to be reproduced in Ver Sacrum—the Viennese Secession’s art periodical which is represented in the exhibition by an issue from the collection of the Getty Research Institute. In this gallery on the Secession, visitors will also find familiar images, including studies for Klimt’s famous Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I.

The Faculty Paintings

The next section of the exhibition explores a turning point for Klimt. In 1894, Klimt and artist Franz von Matsch were commissioned to make the ceiling paintings for the grand reception hall of the newly-built Vienna University. Klimt was to create three paintings representing the disciplines of Philosophy, Medicine, and Jurisprudence. No longer believing in the inevitable progress of humanity so widely espoused at the time, Klimt created a cosmic vision of floating figures delivered up to a fate that was out of their control. He developed a radical approach to the nude, rejecting the fleshy three-dimensional beauty of the classical nude in favor of what might be called “nakedness,” pointing to the realities of the human condition, and achieving a potent vision of the endless birth, death, and suffering of humanity. Klimt’s paintings caused a public scandal and were ultimately rejected by the University, with Klimt buying them back in 1905. The paintings, considered to be his most sweeping view of humanity, were destroyed by fire in 1945. Many preparatory drawings for the “Faculty Paintings” will be on view along with a photomural that creates a composite view of how the canvases would have looked had they ever been installed.

The Beethoven Frieze

The exhibition then moves to a high point in Klimt’s career—the Beethoven Frieze, a painted interpretation of one of the greatest musical compositions ever written, the final choral movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony (1824). In 1901/2 Klimt created this groundbreaking decorative cycle for the Secession building in Vienna, where it is still in situ today. The creative process of this highly elaborate project is evidenced by numerous preparatory drawings, represented in the exhibition by thirteen fine examples displayed according to the order of the narrative. High on the walls above the drawings, the frieze—which depicts mankind’s dramatic quest for happiness—will be reproduced almost in its entirety and practically to scale.

Life Drawing

In spite of the modernity of his practice Klimt retained the academic discipline of drawing studies after the naked or dressed model. Klimt’s studio practice is explored in the middle of the exhibition, which includes an enlarged photo of his last studio. There Klimt hired models, mostly female, to lounge in various poses; for his drawing board he used a stand mounted on casters so he could follow them around the studio as they adjusted positions. The swift, elegant, and often intensely erotic drawings were frequently done on smooth Japanese paper with silvery pencil or colored pencils in red and blue that lent a sense of weightlessness to the flowing forms.

Later Work

In 1905 Klimt left the Secession group to follow an increasingly personal artistic path in which he focused primarily on the theme of the cycle of life. Drawings in this part of the exhibition include studies for his well-known work Three Ages of Women (1905). Even though Klimt saw mankind as caught in the grip of the cycle of life and death, he celebrated the lifeaffirming forces of love and procreation with astonishing poetic force in highly ornamental and modern paintings such as The Kiss and Hope II. The drawings for these iconic paintings are rendered exclusively in lines, with modeling and shading abandoned. Attracted to emaciated figure types, he asked the models to strike poses that would capture the pure essence of eternal human states of emotion such as love, joy, and grief.

The last section of the exhibition includes studies for some of Klimt’s most famous portraits, such as Portrait of Eugenia Primavesi (1913). These late works continue to explore the individual figure and its relationship to the picture plane. Characteristically, he crops the figures at the bottom or top as if to suggest the transitory aspect of life. This section explores the identity of Klimt’s exclusively female sitters, who were almost all Jewish and whose collections of Klimt’s work were confiscated and dispersed during the Nazi era.

Klimt, who died in 1918, drew and painted as assiduously as ever right until the end. He was ever exploratory in his style and his later drawings embraced a lacey manner of delicately curving pencil strokes, embarking on a new emphasis on movement and pattern.