기베르티의 걸작 천국의문 34년동안 복원 끝에 공개

By Laura Lombardi and Ermanno Rivetti

Opening the Gates of Paradise

Why it has taken 34 years to conserve Florence's Ghiberti masterpieces

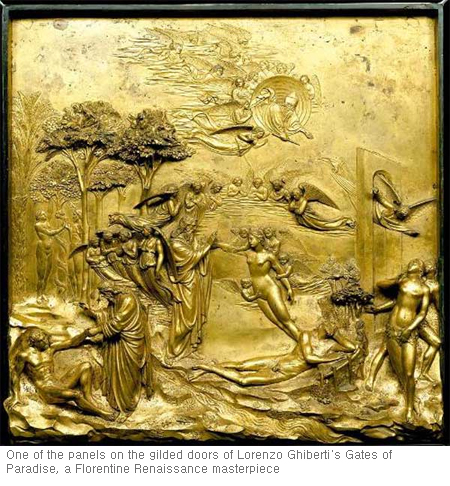

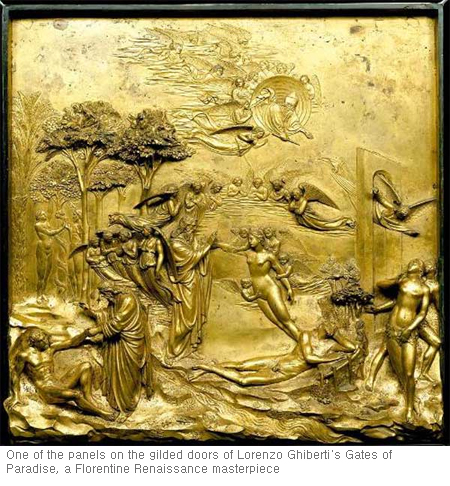

After 12 years of planning and a further 22 years of conservation work, all ten panels from the Gates of Paradise, a Florentine Renaissance masterpiece by Lorenzo Ghiberti, have been restored to their former glory by a team from the Opificio delle Pietre Dure—one of the foremost conservation institutes in the world. The monumental set of gilded bronze doors, constructed between 1425 and 1452, stand at just over five metres tall and contain scenes from the Old Testament. The panels, admired by Michelangelo, once adorned the east entrance to the Battistero di San Giovanni in Florence.

The Baptistry, located in the Piazza del Duomo, was built between 1059 and 1128, making it one of the oldest buildings in the city. Together with the Basilica di Santa Maria del Fiore, also known simply as the Duomo, and Giotto’s Campanile, the three buildings form part of a Unesco world heritage site that covers the centre of the city. Italy’s ministry of culture contributed €3m ($3.7m) towards the project, while the private American foundation, the Friends of Florence, gave €250,000. An additional €500,000 was provided by the Museo dell’Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, which houses many of the works originally made for the Duomo.

The sculpted doors, however, will not go back on their hinges at the Baptistry where replicas have been installed since 1990. Instead, they are set to go on display on 8 September at the Museo dell’Opera. The doors will be installed in their own room in a protective case commissioned by the Museo dell’Opera under guidance from the Opificio, which has overseen the project since it began in 1978. The doors will be moved to a new space following the completion of the museum’s planned enlargement project, which is expected to finish sometime between 2014 and 2015. This new space will enable visitors a 360-degree-view of the work.

Anna Maria Giusti, a conservation expert from the Opificio, says the damage to the panels was caused by excessive humidity which allowed salts to crystallise on the bronze. These crystals slowly corroded small holes in the surface. “The protective casing will guarantee a constant level of humidity at 20%. We used a nitrogen atmosphere to protect the individual panels [which were detached for cleaning], but that is an expensive technique. Now that the door is whole again, we filter the air in the casing, removing dust and harmful gases. It took a year of research to fine-tune this technique.”

Giusti says attempts were made to do without the glass case, but that the plan was too ambitious. “The idea was to create an invisible barrier around the work with the help of dehumidified air pumped out by a ventilation system around the door. This barrier would have prevented the oxygen in the surrounding air from coming into contact with the work. However, this method worked only on a single detached panel—the technology we have today is not advanced enough to deal with the entire door.”

Preliminary investigations on the panels began in 1978 and lasted 12 years until April 1990, when the door was unhinged and transferred to the laboratories at the Opificio. Meanwhile a replica, made by the Opera del Duomo, was installed in its place at the Baptistry. Work stopped for six years while experts discussed the best way to detach the individual panels from the door so that they could be cleaned separately. Giusti, who has headed the project since 1996, recalls how “extraction times for each panel were highly irregular: one could take 20 days and another six months.” The work’s fragile condition as well as the irregular edges of the separate panels complicated the removal process. Furthermore, several of the sculpted figures were in such deep relief that they posed additional problems to conservators when it came to separating them.

After their removal, the panels were washed with a potassium tartrate solution before undergoing an advanced laser treatment using technology developed by the Physics Institute of state-funded Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche in Florence, in which sharp bursts of lasers are targeted on and vaporise pinpointed impurities. These bursts are brief enough to prevent the generated heat from being transferred to surrounding parts of the work, which was ideal for cleaning the panels that could not be detached. Conservators encountered new challenges when fitting the panels back into their original places on the door. “The harder it was to detach a panel from the door, the more difficult it became to put it back,” Giusti says.

Marco Ciatti, the new superintendent of the Opificio, defines the project as “a landmark achievement. It was unique in its sheer scale and complexity, as well as the unforeseen challenges it presented along the way.”